It’s fall, and it’s election season, so there are maple leaves everywhere, real and on placards. Since moving to Toronto I’ve learned to both love and hate maple trees. My back yard is surrounded by them – two huge Norway maples (Acer platanoides) to the west, and although damaged by the ice storm a few years back, to the northeast a magnificent sugar maple (Acer saccharum) with a huge, almost perfectly spherical canopy. I marvel at their beautiful foliage – rich greens in the spring and summer, and gorgeous hues of yellow, orange, and red in the fall. But mostly I curse the Norway maples – first it’s all the crap from the flower buds, then two rounds of seeds (the “keys”), a continuous rain of branches, twigs and diseased leaves all summer long, and then the grand finale, thousands of leaves that have to be raked and bagged every fall, usually in cold, wet weather.

My first spring here I noticed the maple keys tend to form little clusters on the ground, somehow managing to get quite stuck into the earth. Was this some evolutionary adaptation that promoted germination? Perhaps, but when I pulled these ugly, ragged little clumps out of my garden beds, quite often a surprised worm would quickly retreat down into the soil. Intrigued, I did some investigation on the Internet, and discovered I had stumbled on a symbiotic duo of invasive species that are spreading throughout Central Canada’s deciduous forests, crowding out native species and upsetting the natural balance.

Norway maples (Fig. 1) were introduced by Europeans back in the 1700s, but because of their fast growth, large shade canopies, and ability to thrive in poor urban conditions, they became a very popular replacement for elm trees lost to Dutch elm disease starting in the 1930s. They are now everywhere, and are a widely despised invasive species, yet are still sold in garden centres and big box hardware stores. They have spread out of the cities into Canada’s forests. Little light gets through their canopies and this, combined with their dense and shallow root systems, makes it very difficult for other tree species to grow, resulting in declining biodiversity.

Lesser known, the European earthworm is also an invasive species, brought over as early as the 1600s in ship ballast and plant root balls. Interestingly, the last ice age effectively killed off whatever native earthworm species there were in Canada and well into the US. As the ice sheets retreated a few worm species in the southern US slowly expanded their range north and were then joined by interlopers such as the Europeans. While the European earthworm can’t really be accused of pushing out native species, it has had a deleterious effect on Canada’s ecosystems. Canada’s tree species evolved to extract nutrients from worm-less ground; these recently arrived worms bring nutrients to the surface and convert them to more easily accessible forms, favouring shallow plants, in some cases invasive ones, at the expense of the native trees. The worms are basically “stealing” nutrition away from Canada’s trees and giving them to other plants and shrubs.

Now, the point of this lengthy introduction… European earthworms have evolved to harvest Norway maple keys. At night they come up and gather maple keys, pulling them partly down their holes. They then lie just below the surface and munch away on the keys. Norway maple seed pods have evolved to be worm resistant, and so a perfect symbiotic relationship has formed: the worms get the nutrition from the blades of the keys, while the Norwegian maples get their seeds pulled down into the ground, thus improving the chances of successful germination. All the other native maple species have no evolved protection, and their seeds are ingested by the worms, thus further lowering their reproduction rates.

This sort of ecological tragedy has played out thousands of times over the course of human history, sometimes in spectacular and well known fashion, such as the cane toad debacle in Australia, but more often unseen, even under our very feet as is the case with the European earthworm in Canada. Some invasive species in Ontario include, “purple loosestrife, garlic mustard, buckthorns, emerald ash borer, zebra mussels, dog strangling vine, reed canary grass (Phragmites), and round goby,” (Conservation Ontario, 2019) and that’s just a short list, to which I’d like to add the infamous lamprey eel, just because it looks so nasty (Fig. 2). All these and many more are thriving, often putting native species at risk of extinction. In Alberta we’re reminded of this by the highway signs instructing us not to bring firewood into Alberta and to ensure boat hulls have been washed to remove potential invaders. And of course the efforts to keep Alberta rat free are well known and celebrated. There is an organization – the Alberta Invasive Species Council – devoted to keeping invasive species out, not only to protect Alberta’s native species, but also to avoid the potential economic losses that can be inflicted by invasive species. Alberta is particularly vulnerable to invasive plants species; the AISC website has an album with images of the 85 most common ones (Alberta Invasive Species Council, 2019). While sometimes invasive species enter by happenstance, such as windborne seeds, or inadvertent passengers, often they are deliberately introduced to address one “problem” and then create calamitous unintended consequences.

Feral versus invasive

What is the difference between an invasive species and a feral species? I found an interesting “Final Position Statement” from The Wildlife Society which starts with these two paragraphs:

Invasive and feral species present unique challenges for wildlife management. The Wildlife Society defines an invasive species as an established plant or animal species that causes direct or indirect economic or environmental harm within an ecosystem, or a species that would likely cause such harm if introduced to an ecosystem in which it is non-indigenous as determined through objective, scientific risk assessment tools and analyses. Feral species are those that have been established from intentional or accidental release of domestic stock that results in a self-sustaining population(s), such as feral horses (Equus ferus), feral cats (Felis catus), or feral swine (wild pig, Sus scrofa) in North America. Feral species are generally non-indigenous and often invasive. Whereas invasive species are typically non-indigenous, not all non-indigenous species are perceived as invasive. For example, species introduced as biological control agents and some naturalized wildlife species, provide significant economic benefits while not resulting in significant or perceived harm to native ecosystems. Similarly, some indigenous species can be perceived as invasive when population increase or range expansion beyond historical levels disrupt ecosystem processes, resulting in economic or environmental harm. Determination of an invasive species can vary across regions based on the presence of local economic or environmental harm.(The Wildlife Society, 2016)

This is a very human-centric statement. It implies that we humans are to be judge and jury regarding how species should be perceived and used, and especially in the second paragraph, that we humans can be trusted to balance the benefits and harms created by introducing species. I get nervous when humans think they can be trusted to play god – I find the term “wildlife management” to be particularly arrogant, and “biological control agents” to be quite frightening. The language in the statement above, while well-meaning, reminds me of what was being thrown around in the heyday of eugenics around 100 years ago, albeit in a non-human context. I think this whole discussion around feral and invasive species leads to interesting and perhaps surprising moral and philosophical perspectives. For example, should the way an invasive species was introduced determine whether we view it as good, bad, or neutral? If an invasive species delivers benefits from a human perspective, does that automatically make it good? If one species drives another into extinction, is that a bad thing, or is it just natural selection at play? Should morals be part of any discussion about nature? I will delve into questions like these in more detail following a short rogues’ gallery of invasive species that were introduced thanks to humans and which caused unintended consequences.

Best intentions gone wrong

The Internet is full of invasive species lists – we all know the obvious ones such as the cane toad, kudzu, zebra mussels, Asian carp, etc. Here are a few obscure and interesting ones.

- Monk parrot (Myiopsitta monachus)

This pretty bird (Fig. 3), which is also known as the Quaker parrot or parakeet, has expanded its original range in Argentina and neighbouring countries to establish itself as a feral species throughout Europe, the Caribbean and Central and North America, in most or all cases via the escaped/released pet route. There are viable, sustainable populations as far north as Chicago and Vancouver. There is debate whether it poses a significant threat to agriculture. What is interesting is that each feral population tends to develop a localized song dialect, which will likely impact mate selection, a possible first step towards the development of new species. - Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

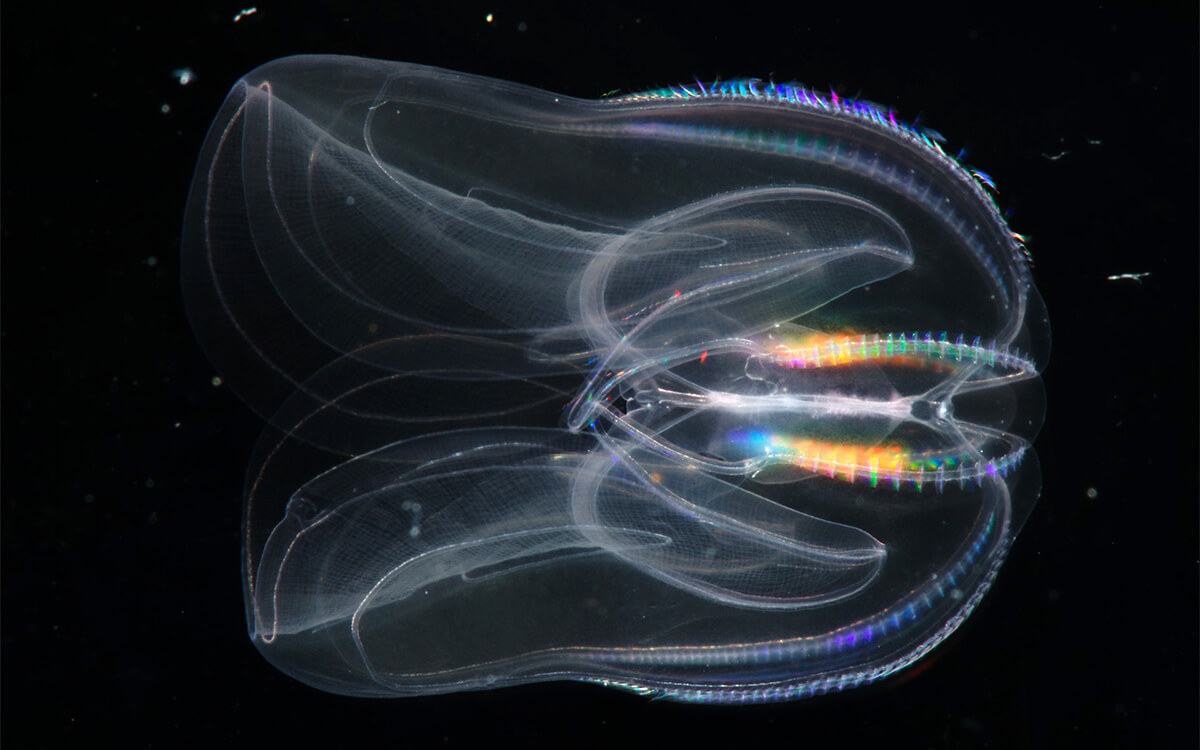

The dandelion (Fig. 4) certainly isn’t obscure, but here are a few interesting facts. The dandelion probably was brought to North America on the Mayflower, for its medicinal and nutritive properties. It is capable of reproducing asexually, essentially cloning itself. The entire plant is edible and contains high levels of vitamins A, C, and K, along with calcium, iron, potassium and manganese. It is a valuable early spring food source for a variety of birds and insects. Its scientific name Taraxacum comes from the Persian word tarashaquq. Shorter stemmed varieties have evolved as an adaptation that avoids lawn mower blades. I find it ironic that while viewed as undesirable invasive species in North America, the dandelion actually serves to create more biodiversity within a human imposed monoculture, the lawn. - Sea Walnut (Mnemiopsis leidyi)

Ships use water as ballast, and this has introduced numerous invasive species into new habitats. This sea walnut (Fig. 5) is a small (~10 cm long) type of comb jelly native to the western Atlantic, but is now invasive in the North, Baltic, Black and Caspian Seas thanks to this. It devastated local fish (and seal) populations in those west Asian bodies of water, because it tends to eat the eggs of fish there. Recently marine biologists have achieved an apparently sustainable balance by introducing a different type of comb jelly (Beroe ovata) which eats the sea walnuts. One bizarre feature that sea walnuts possess is that they use temporary anuses – when pressure from waste products in their stomachs reaches a certain threshold, a temporary opening develops, and then closes up again once the waste has been expelled. This happens about once per hour! - Any number of species in Florida

Florida must be the world leader in number of invasive species hosted. It’s probably because the state offers ideal habitats for many common pet species which tend to escape or get released by delinquent owners. Some prominent ones include the Burmese python, the Nile monitor lizard, and the Green iguana. Here are three you probably have not heard of:

Figure 6. Giant African land snail. Used under Creative Commons 3.0 (Jenner, 2010).

Figure 7. Conehead termites. Used under Creative Commons license 2.0 (Dupont, Nasutitermes corniger, 2008).

Figure 8. Gambian pouched rat (Public domain, courtesy US Fish and Wildlife Services). - Giant African land snail (Achatina fulica)

This snail (Fig. 6) eats voraciously, outcompeting indigenous species. Originally found in East Africa, it is now invasive in many regions across the globe, not just Florida. It carries several plant pathogens which afflict some of Florida’s main agricultural products, and acts as a vector for some human diseases such as lungworm (it tends to eat rat feces). The term giant is deserved, as these snails grow up to 20 cm in length. - Conehead termite (Nasutitermes corniger)

Another voracious eater that has established a toehold in Florida, raising fears that it will spread throughout North America, given that it can survive in a broad range of climates. These termites (Fig. 7) forage above ground like ants (versus tunnels like most other termites) meaning they can work very fast. They eat anything made of cellulose, so for humans the biggest concern is the destruction of wooden structures such as homes. - Gambian pouched rat (Cricetomys gambianus)

The Gambian pouched rat (Fig. 8) is actually fairly dissimilar to other species of rats such as the Norwegian rat (those damn Norwegians again!) which have proven to be extremely successful invasive species, their numbers increasing in step with those of humans, whose urban habitats they exploit. This African species is large, omnivorous and more suited to rural and wild environments. The Florida infestation started with the escape of a founding population from a pet breeding farm. A 2003 monkeypox outbreak was linked to this type of rat, which placed them on the hit list of the US Fish and Wildlife Services and Florida Wildlife Services, who are working together to eradicate the species. A typical female Gambian pouched rat will produce about 20 young rats in a 9-month period (5 breeding cycles, 4 offspring per litter), so good luck with that. Being nocturnal with poor eyesight, they have extremely sensitive noses, and recently have been trained to sniff out land mines and tuberculosis, at about ¼ of the cost of a canine equivalent.

- Giant African land snail (Achatina fulica)

A different perspective on invasive species, extinction and speciation

Let me finish up with an alternative perspective meant to provoke thought. The consensus opinion regarding human-related species extinction – not only due to invasive species, but also habitat loss, over-exploitation, pollution and all the other factors – is that it is a bad thing. No, a terrible thing. I definitely feel that way – the other day I was reading about the last surviving great auk, a female, and the tragedy of it had me on the verge of tears. But…

Nature is inherently tragic – it is essentially a huge, complicated, integrated food chain where the life of almost every entity relies on the death of others. At every scale there is death… every millisecond must see thousands if not millions of individuals snuffed out, be it plants, animals, insects or other live things, and over millennia of course there are extinctions, always have been, always will be.

There is no argument that humans have sped up the rate of extinction, at least temporarily, but are human-caused extinctions unnatural? The human species is no different than any other species. We too are part of the natural world. We may alter our environment more than other species, but that is a matter of degree. Just as the Earth produces volcanoes and other natural disasters that cause extinctions, so too can it produce species that drive others into extinction over time. We happen to be that sort. We are a natural factor, not an unnatural one, not divine or different in some special way, except perhaps we have a much higher self-awareness and ability to foresee the impacts of our actions. That doesn’t seem to stop us from destructive behaviours. I think of humans like bad guests renting an Airbnb for one awfully destructive weekend. But just as the Airbnb house will survive and recover, so too will the Earth and its life forms, as long as there are a few DNA-based species still kicking around. The Earth has survived previous threats to its life, and so too will it survive humans – we will likely be mere blips over the billions of years of life that have already passed, and the likely billions still to come. DNA-based life, with its ability to adapt and evolve, is robust and resilient.

What does happen when a species becomes extinct? What happens when humans create new ecosystems or alter existing ones so dramatically that species are threatened? What happens when a species is introduced to a new or different ecosystem and becomes invasive? These types of questions can be better understood and answered when the process of speciation is added to the conversation along with extinction. Lately the focus has very much been on the latter, but speciation, when one species splits into two or more species, is occurring all around us, very slowly. One would expect that as the factors, many human-related, causing more and faster extinctions accelerate, so too would speciations. This indeed does seem to be the case, although it is hard to discern given that speciation takes a long time to fully occur. But a key point is that whenever a species goes extinct, an existing ecosystem is dramatically altered, an entirely new ecosystem is created, or a species is introduced to a new ecosystem, then the conditions are ripe for speciation. Let me give you an example.

The apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella (Fig. 9), is native to large parts of the US. It evolved to feed on hawthorn berries. When Europeans introduced apple trees to North America, some apple maggot flies were attracted to this new fruit. One would not expect an expanded diet to result in a new species. However, these maggot flies only mate on the plants they feed on, so what happened was that a new population of apple maggot flies that fed on apples instead of hawthorn berries became isolated from the population that remained on the hawthorns. DNA analysis reveals that the two populations exhibit different allele frequencies, thus confirming that speciation has begun. Of course, it will take many generations until the split is complete and the new species is no longer able to breed with the original species.

CSEG members who have worked in downtown Calgary long enough will remember how it was considered unusual in the mid-1980s for ducks to overwinter in Prince’s Island ponds. Over the years that population has grown and I would guess is a candidate for speciation, with one population continuing to migrate and the other not. Eventually they will probably split, with the non-migrating birds gaining unique cold weather adaptations. In their paper Speciation and the City, (Thompson, Rieseberg, & Schluter, 2018) argue that urban environments are perfect habitats to observe speciation in progress, as populations that survive and thrive in such environments are likely to be isolated from their rural relatives.

To cut to the point I’m making here, while the loss of species due to extinction is a terrible thing in an emotional sense, and we should feel ashamed and guilty as a species that should know better, from a purely rational perspective life will adapt to any changes in the number and nature of the Earth’s ecosystems, including via speciation and the creation of new species. This means the current loss of biodiversity will inevitably be a temporary state. When viewed from this perspective, feral and invasive species are just part of this process. We have a tendency to see everything through a moral lens, but nature is morally neutral, and humans are just a species that has evolved to exploit and disrupt the ecosystems it finds itself in.

While writing this article, I began to discern some parallels between the invasive species and immigration debates. Both involve a central concept, legitimate or not, that there exists some pristine/pure/primordial state to which we should strive to return. This got me thinking on the topic from a totally different perspective. Upon analysis what might appear at first as a black and white issue is very much a landscape of greys. Should a species introduced by floating in on a log be allowed to remain in a new habitat, while one that came in the hold of a ship be eradicated? What if the log had been felled by a chainsaw? How far back should one go to establish what the pure state is? The reality is that the natural world is a messy place, there is always going to be a coming and going of species in time and space, each one’s story a drama in itself, full of beauty, tragedy and joy, hope and despair. The human species is just one strand is this complicated story of life on our planet.

The issue is further muddied by several confusing realities. With the climate changing rapidly, should we favour native species which are struggling to survive in a changing habitat over a newcomer species which is thriving? What if an invasive species is going extinct in its native territory? What if an invasive species is now performing a critical role in an ecosystem in place of another species that has gone extinct? These and other stimulating questions are increasingly being asked, such as in this National Geographic article, “It's Time to Stop Thinking That All Non-Native Species Are Evil” (Marris, 2014).

I have moved towards a bifaceted stance on this topic – in the short term and emotionally/morally I am appalled at what we humans are doing to our planet, including the introduction of invasive and feral species, but rationally I am confident that in the long term our planet is safe in the hands of Mother Earth and her killer app, evolution, and that life will prevail in all its glorious diversity.

Share This Column