Writing an engaging novel is challenging. Being a good scientist is also difficult because good science requires almost inhuman discipline and humility. Facing up to our own limitations is often viscerally painful, and change may be the most difficult thing of all to deal with. Looking back on my former career as a geophysicist and forward onto my new career as a writer, I have benefitted from appreciating all of these seemingly disparate challenges. My weaknesses, together with my scientific background and the need to change, have somehow all been conflated into an inspiration to write a series of fantasy novels. It might sound like an unlikely combination, but let me go further afield and say that Star Trek went here first.

In my formative years, I read Lord of the Rings and watched Star Trek. I recently retired from my career as a geophysicist in the oil and gas industry with the goal to write fiction. I had written plenty of non-fiction articles and papers as a professional geophysicist, but creative writing had always been on my mind. I guess I never really forgot Star Trek even though watching it is now decades in the past. As I grew as a scientist, this desire became even stronger. The very best scientists that I knew in industry, people such as Peter Cary or Jon Downtown, were extremely parsimonious in their conclusions, so careful in what they said. I came to understand that this caution was an important quality in a scientist, that it was part of the humility and discipline of the scientific method. Science, after all, is not an answer, is not a fact or a law, but is the never-ending systematic pursuit of understanding. There is no permanence in our understanding of the world, only the goal of eventually understanding the world better. While we provisionally accept many scientific ideas until they are disproven, it would not be wrong to suggest that it is a fantasy to claim that we truly know anything for sure. While I struggled to understand elements of the science of geophysics, part of my mind dwelled on this fantasy that we truly know anything. Going further, I wondered if there might be a good story in the question of the certainty and immutability of knowledge, or perhaps even in creativity itself. Fantasy and speculative fiction have, after all, long been genres where questions such as these could be engagingly explored.

The original Star Trek series, while now very old, is a great early example of insightful science fiction. Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek was far ahead of its time in its treatment of social issues. It was also hugely entertaining. Star Trek did not just boldly go where no one had gone before in space, it boldly dealt with issues such as race, discrimination and some of the ongoing violent conflicts of the time. Being a science fiction show allowed Star Trek to go to these places without losing its audience. The show made a point without being preachy or off-putting and dealt with serious issues while avoiding being either too Pollyanna or too grim. Ultimately, Star Trek was positive, not just for its attitude, but for the fact that it took on these issues when few others did. Star Trek was such a meaningful show that it still affects people today. As I prepared to switch careers to writing, Star Trek inspired me to the opinion that fantasy would be a suitable genre within which to write my stories.

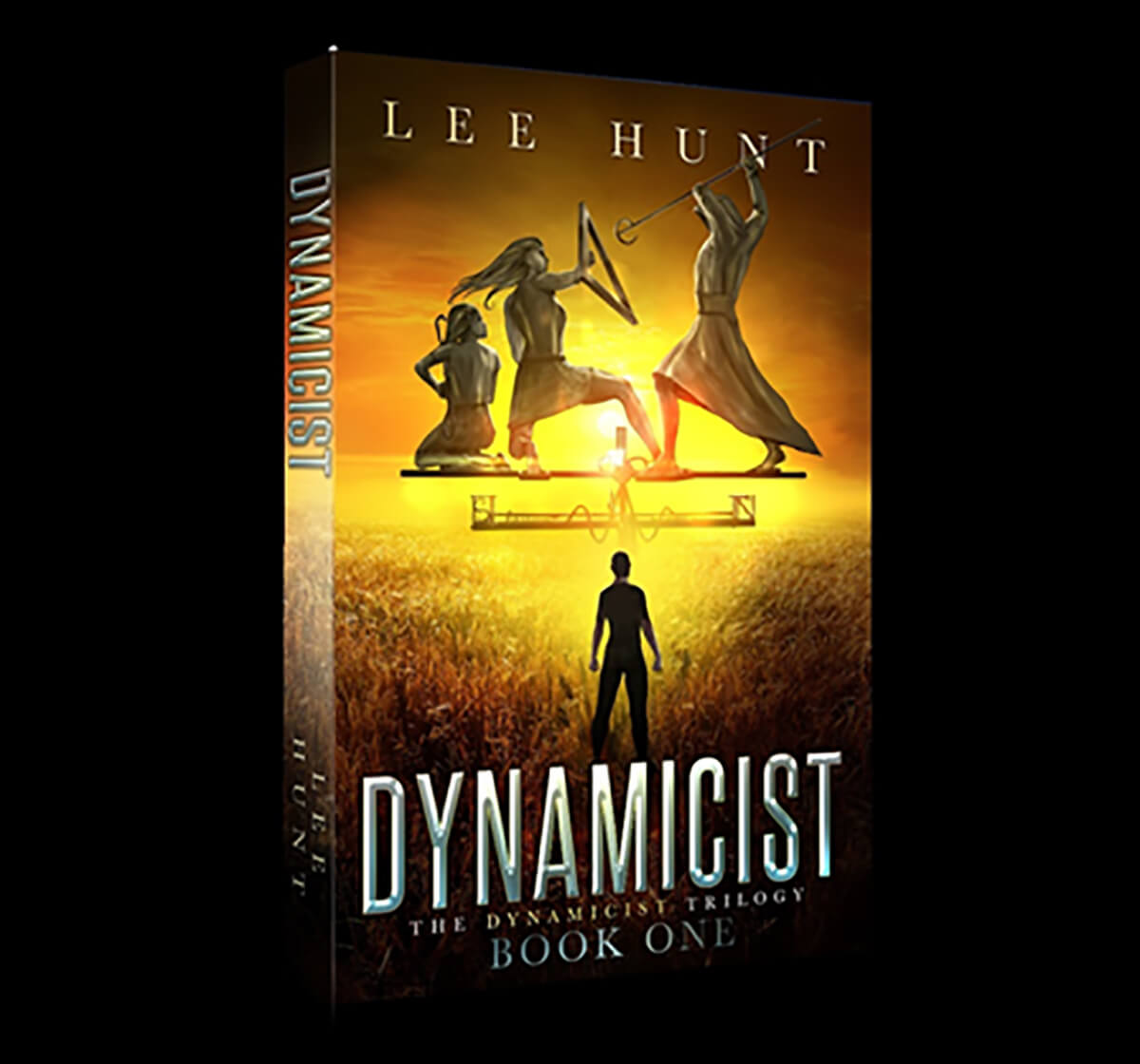

Dynamicist is the first book in a trilogy that explores ideas such as the difficulty of change, the nature and limitations of knowledge, and the effects of traumatic memory. These serious themes are all over the news today in ongoing environmental debates, social unrest, and even in the battle for objective truth in the news itself. These topics can become so heated that even a request for civil discourse on them can be treated as provocation. In Dynamicist, I have strived to write an engaging, character-driven story that treats some of some of these serious issues in a way that is non-threatening, even in the current hyper-sensitive times. Much of the early part of the trilogy deals with a new breed of wheat, which seems innocuous enough —even mundane. But in the world of Dynamicist, inventing something new historically provoked a transcendental being—a god—to appear and kill the inventor. Fear of change was made manifest by certain death at the hands of a terrifying and unbeatable being. Although this punishing deity no longer appears, the people of the world are still affected by a history where creativity was costly.

Scientists know that doing anything is costly, least of all change. This important idea forms the second law of thermodynamics, that entropy in a closed system always increases. It frustrates our every search for simple, costless solutions. In the real world, there is always a price to be paid. This conundrum appears throughout the trilogy and is at the heart of the magic system within the Dynamicist world. The system is not mystical, the magic using people do not refer to themselves as mages. The title “wizard” is an insult. The magic users call themselves dynamicists and operate around a structure of signal and inverse theory, though they do not use those terms. In a fitting metaphor to the thematic idea of change being difficult and expensive, their use of dynamics is costly—sometimes spectacularly—in thermodynamic terms.

Of course, it is always easier to ask other people to change, rather than to change yourself. I have learned this in innumerable ways through my life—I still learn it to some extent in my daily failings and learnings. For example, as a scientist, I needed to learn to be patient and seek out data, and to attempt to set aside my biases.

As an athlete, I had to learn to accept my severe limitations and respond appropriately. I was born without a right pulmonary artery, which effectively meant that I only oxygenated out of one lung, which probably resulted in me being prone to lower respiratory infections such as pneumonia. When I was 25 years old, I contracted a viral pneumonia, likely as a sequel to an influenza A infection. This brought about something called Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, which very nearly killed me and ultimately left both my right and left lungs severely damaged. I was so sick that at one point, doctors informed my parents that I had a 2 percent chance of living. I did not, however, die. After recovering as best I could, I resolved to live a normal life. I attempted an Ironman in 2008. I failed to complete the event, and suffered numerous subsequent cases of pulmonary edema due to the absent right pulmonary artery and the severe damage to my lungs. I did not learn from my issue and treat it well enough. It is uncomfortable to admit that I had insufficiently understood myself, and even more uncomfortable to fail. I had to face up to reality and change. With that in mind, I eventually committed myself to understanding my pulmonary issues better and engaged with doctors and professional coaches to determine strategies and an intensity discipline that might allow me to (a) successfully complete my goals and (b) survive them. In 2012, armed with a strategy that accepted my health limitations, I completed the 2012 Ironman. Alive and well, too.

I wish all the members of the CSEG only the best in their own desires to be good scientists, communicators, and that their efforts to bring about positive change in themselves or in the world can find success. If you are interested in reading Dynamicist, look it up on Amazon, and let us not forget to check out the original Star Trek series if it shows up on television.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article