Introduction

James Michener (1992) wrote, "The writer who sits at his or her desk with an empty piece of paper staring back is like the explorer who stands at the edge of a new continent, uncertain of how to proceed" – an exciting but perhaps difficult position. The goal of this article is to provide that intrepid explorer with some additional tools, strategies, and thoughts to aid in the exploration and development of the new realm. In addition, the explorer will likely want (or have) to go back and tell others the fascinating story of the adventures had. So we'll also discuss how our brave speaker can enthuse, persuade, and educate the audience.

Much of the value of our geophysical work does follow from conveying it to others, so we must communicate, both accurately and compellingly, in writing and in speaking. This paper presents some standards, practices, and rules-of-thumb that we (and others - see References for General Reading) have found useful. A number of pitfalls and mistakes are also described mostly from our personal experience.

The communication process really starts early in the work or study itself; the deeper our understanding of the problem, the more clearly we will be able to describe it. During the work, it is essential that we continue to ask ourselves probing questions on the truth, completeness, and relevance of our solutions. Critical self-questioning will not only lead to better answers and greater confidence, but will help us to anticipate and respond to questions from associates or an audience.

The development of a geophysical technique or case history is not truly complete without presentation, review, and revision. There are many reasons for this. Presentation is where we communicate our work to others. In the subsequent review, comments, praise, and criticism come back to us. This is essential. Praise is important to let us know that we're on the right track, that our work is useful. It's warm and fuzzy and motivates us. Constructive criticism and suggestions are often necessary: For example, our study can have implicit but inappropriate assumptions that we don't recognize but others may; it may have unrecognized inefficiencies. Furthermore, it may use less than ideal methods compared to those used, perhaps obscurely, elsewhere. Review, by associates internal and external to our organization, may help with these problems. In revision, we upgrade and enhance our work by taking into account the review discussion.

In all stages of the technical development, it is important to keep notes, references, figures, plots, etc. These should be organized, perhaps loosely, in a file, notebook, or word processor. As the study progresses, much of the final presentation can already be underway because we have kept snippets of writing, have jotted down references, drafted a few figures, or generated some plots. This evolutionary approach to the final paper or talk will minimize the amount of work required at its conclusion: Most of a paper (structure, graphs, discussion, references) may already have been done before writing begins in earnest! Furthermore, keeping complete records will increase the accuracy of their discussion the study might last longer than the precision of our memories.

Perhaps the most important aspects of communicating or transmitting technical information rely on personal qualities: patience, empathy, and energy. We need to have patience with an audience because they generally aren't as familiar with our work as we are. They will require adequate background information about the study, our motivation for doing it, and an appropriate rate of information delivery. We need to have empathy with the audience, to present our results not as we think of them but as the audience can understand them. Furthermore, people will likely try harder to follow us, if they know that we are attempting to present in a considerate way. Finally, all of this takes energy. We have to want to communicate, to enthuse, to be accurate and understood. For many reasons (scientific, personal, financial, inspirational), we believe that good communication is eminently worth it.

Writing a Technical Paper

There are many different forms of technical writing including: e-mail, memos, letters, abstracts, short notes, posters, proposals, reports, course notes, refereed papers, and books. These various forms have different lengths and depths, but all share a similar structure and intent. They must be clear, credible, and enlightening. The following gives a possible procedure for going about your writing:

The Eight-fold Writing Path

- Define the subject

- Decide on form and deadline

- Gather and review material

- Draft an outline (major ideas, sections)

- Ferment, review, finalize the outline

- Start writing (free flow)

- Reorganize

- Edit

Following a route something like the above can avoid writer's block, stalling, and lack of progress. Further ways to prevent writer's block are: Start writing anywhere... front, back. headings. references. introduction; anyplace... ; don't worry about spelling, grammar, or anything editorial that comes later – just get some words down; free associate: talk about the subject then return to writing. Keep moving ahead. even if only slightly.

There are also numerous variations in the style of scientific writing. The style depends on subject matter, the purpose (inhouse report, journal paper, agency document, etc.), the nature of the content (quantitative with data analysis, qualitative or descriptive, review of previous work, etc.) and other factors. However, summarized below are the major common elements of most geophysical papers:

- Title

- Authors

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Geology/Study area

- Data Acquisition

- Derivations/Methods

- Data Analysis

- Interpretation

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusions or Summary

- Future Work

- Acknowledgments

- References

- Appendices

- Tables and Captions

- Figure Captions

- Figures

Let's expand a bit on some of the headings given above.

Title: It should be as brief as possible while still conveying the topic or problem treated. The title should contain significant words suitable for classifying or indexing the paper.

Author(s): The name(s) of author(s) should be followed by affiliation(s) and address(es).

Abstract: The abstract or summary is critically important as it is likely to be read by 10 to 500 times more people than is the entire paper (Landes, 1966). It is not an introduction, nor a table of contents, but a summary of the essential results of the study described in the paper, including its principal conclusions. Enough background information should be included to make the results meaningful to the reader. Abstracts vary in length depending on the nature and length of the paper. However, they usually range from about 75 to about 400 words. Short notes or commentaries may not need an abstract.

Introduction: This should set the stage for the paper so that, at its end, it is clear to the reader just what the problem is, what progress has been made in the area previously, and how you are going to tackle the problem and enhance or advance the general state of knowledge in that area. This may include a brief literature review, statements of the area of study, the type of data gathered, the method of analysis, and/or some other indication of what the reader will encounter if indeed he/she is moved to read further.

Main Body: This is extremely variable but usually is comprised of several sections. They may deal with, for instance: the survey area, geologic setting, experimental setup and procedure, data acquisition, mathematical derivations, methods, data analysis, error analysis, interpretation, results, etc.

Discussion: Often it is suitable, or even necessary, to discuss the significance or limitations of your study rather than just presenting it without comment. Sometimes this discussion may be incorporated into various sections of the main body; sometimes it may be combined with the Conclusions. We are provided an opportunity in the Discussion section to be a bit editorial, qualitative, or even speculative.

Conclusions: The important results or conclusions of your paper should be synthesized here into a few briefly phrased sentences. Point form is suitable in some cases. Generally, the conclusions are previously stated more summarily in the Abstract. New ideas or comments should not be introduced in the Conclusions.

Future Work: Frequently, the study may have some unresolved issues, or raise new ideas which could be the subject of future research. These should be discussed briefly in this section.

References: All statements of an assertive nature should be proved or referenced. Unfortunately, most ideas aren't new, so we need to acknowledge relevant authors. A complete bibliography is a great service to your reader and a conscientious author's responsibility. Referencing is not just a courtesy in many cases but a formal obligation. Those references cited in the text, usually by author and year, should be listed alphabetically (then chronologically). Background literature that is not explicitly cited should be listed separately under some heading like References for General Reading.

Appendices: An appendix contains material which is important enough to be included in the paper, but not critical to understanding the main thrusts of the study. Similarly, if a secondary point requires lengthy or separate discussion, which could detract from the continuity of the text, it could be better placed in an Appendix. Supporting mathematics or derivations are often put in an Appendix.

Figures and Tables: These should have captions or headings which enable them to be understood, in their essentials, independently of the text of the paper. Imagine the busy reader thumbing quickly through your paper stopping at only an interesting figure and its caption. Figures may be embedded in the text as they are cited or grouped in order at the end of the paper. Numbers without units are of very limited use (unless dimensionless to begin with). Use clear and complete annotations on the axes, lines, or data points of graphs. Commentary on a figure, apart from essential annotation (units, labels, legends, north arrows, etc.) should, as much as possible, be put into the figure caption. This organizes the information better and more economically.

General comments

Boldly state assumptions and limitations. This contributes to the honesty of a paper and helps with clarity and understanding. It also pre-empts the critic's strike. Most scientific readers will be more receptive to a reasonable theory, perhaps understated and qualified, than one with hidden problems pushed like a sales pitch.

Use correct, moderately formal grammar, and spell properly! There are spell checking and grammar-assisting word processors to help in these regards. Careful though, word processors don't necessarily have a good grasp of meaning – know more miss steaks that ewe can knot sea. One word processor of ours didn't have the word geophysics in its dictionary and came up with its best replacement – goofiness.

Be careful with long (more than about 3 lines) or run-on sentences. They're hard to follow and understand. Having colleagues read and critique your paper will likely help it considerably. A plain style of writing which uses well understood words, avoids repetition, and uses active tenses will likely be most appreciated. William Safire in his book Fumblerules calls attention to some issues of style, "Never, ever use repetitive redundancies; Avoid trendy locutions that sound flaky; Never use a long word when a diminutive one will do; Last but not least, avoid cliches like the plague." There are a number of useful guidebooks on syntax, word-choice, style, etc.(e.g., Cochran et al., 1979; Bernstein, 1981: Venolia, 1983; Buckley, 1992).

Use appropriate technical standards (like SI and SEG in our case) in referencing, spelling, and stating units. The January issue of GEOPHYSICS gives a detailed guide to these.

Attempt to be concise and brief. There is a movement in Journals and elsewhere toward shorter papers. They are often easier to grasp and digest. Also, a paper has more impact if it has one or two main points to convey. Important, new ideas can become diluted or even lost in a long, structurally complex paper. For better or worse, most people are busy and only have a short time for your paper.

The final, written paper must have a logical, coherent flow; it will frequently start with the simplest and most basic ideas, then develop in complexity. Often, the order to best present the work is not the same as the chronological order in which the work was done.

For most people (even some of the great authors), writing is not easy. Don't be alarmed if you go through 20 drafts of a paper - that's what word processors are for. It is important to continue reworking sentences and concepts until they are clear. Revising is easier than writing the original script, so don't try for the perfect paper in the first draft. In the end, the critical matter is to get your work evaluated and appreciated by others. Hopefully, the paper will be good; realistically, it won't be perfect.

Finally, enjoy your paper! As geophysicists, our production is often in the form of a report or document. It can be exceedingly satisfying to produce a paper which has met your literary and technical goals. Your work and writing is something of which you should and can be proud.

Presenting a Technical Paper

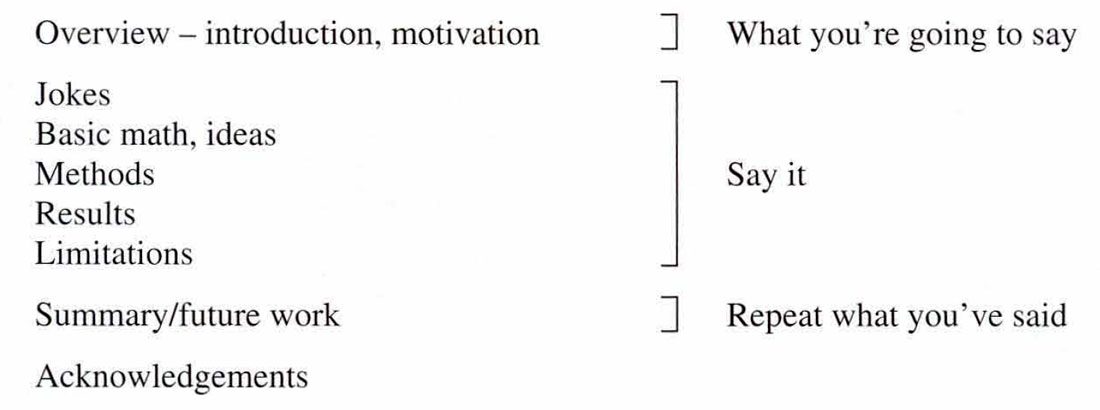

A technical talk's structure is often very similar to that of a written paper. However, in giving an oral presentation, it is critical to be selective about what you include. The talk should generally be considerably simplified if derived from a paper. A possible structure is shown below:

Slides and their presentation

As a general guideline, we suggest using about one slide per minute. This gives the audience adequate time to digest the information on the slide but provides new material often enough that interest isn't lost. The title slide should include authors and their affiliations. It is also helpful to use an outline slide to ease yourself and the listeners into the talk. Each slide should be completely described, including, for example, the axes on plots. Remember that you are familiar with your slides but the audience won't be. To finish the talk it is helpful to include a conclusion slide – this is the information that the audience will be left with.

There are many tastes in slide design, but using a dark background and bright colors for lettering on your slides will help their readability. Seismic sections, on the other hand, are often best seen as black traces on a white background. Remember, in some halls, viewers may be half a football field length away from the screen give them a chance to read the slides by using large slide-filling letters and figures. Four or five lines of text on a slide are usually plenty. If you are using two screens, try to arrange your slides so that they step through sequentially in pairs. Complex slide changes are stressful to the projectionist and prone to error. It is ruinous for the talk, speaker, and distracting to the audience if slides get out of order.

It has been said that mathematics should be kept in your office, with the lights down, and the door closed. Viewers of talks with dozens of equations scrawled on a transparency would likely agree. However, mathematics can be effectively communicated in a talk. It just takes time. The audience will be lost unless every variable in the equations, limits of the integration, etc. are described and explained. One or two equations per slide is generally all that can be assimilated by viewers. An audience of processors might like equations more than geologically oriented interpreters.

Plan your talk carefully to fit the available time allotment. This is critical at most meetings, but especially at large gatherings where there may be many simultaneous sessions and a tight schedule. It's embarrassing to everyone if a session chairman has to give you the hook – terminate your talk. Know where in your talk you should be at half time; slow down or speed up accordingly. Revise the talk until you feel that there is a logical, compelling flow to it. Practice your talk and know the order of your slides: Someday, someone will likely dump your slide carousel just before you are to speak. Reassembling it fast requires familiarity. The continuity of a talk is increased greatly if you introduce the next slide before it is displayed. Visit the room before you talk, stand at the podium to get a feel of the room. See where the laser pointer and the audio and slide controls are. Review your carousels before your talk to find any reversed or inverted slides, never a real treat to an audience.

Standard public speaking rules

Many books and organizations tell us that good speakers are not just born, they are made. Practice works. Some of the following points may help improve your presentations. Attempt to modulate your voice (this helps maintain an audience's interest in your talk, and perhaps their consciousness). Speak loudly enough for the whole room to hear you. Rather than "um","ah", etc., try to say nothing. Brief silences or pauses in the talk give the audience time to think about what you have said. It is important to maintain eye contact with the group at large and to avoid talking to the screen. People don't listen well if they're not being spoken to directly. Avoid reading the text of your talk, except the introduction and conclusions (if necessary).

Most people who perform publicly (whether musicians, actors, or geophysicists) experience some degree of stage fright or performance anxiety – a first talk in front of a CSEG Luncheon of 900 colleagues is a stressful experience. Knowing that you are prepared and practiced minimizes this concern. Demanding a credible, but not brilliant performance from yourself can help too. Being less critical of the performance of others seems to allow one to let up on oneself too. Remembering that you have been asked to talk, and thus are giving to others, may make the situation less difficult for you. If you are nervous, have small cue cards with you at the podium. Have one card per slide and write in big letters the main points about the slide on the cue card to jog your memory. We suggest adopting a fairly formal stance (e.g. hands out of pockets, standing straight, moderate use of hands). There are other radical and valid styles, but generally in science we want to communicate technical points not theatrical excess.

If using a laser pointer, turn it off when moving between places on the screen to be emphasized. The eye follows the pointer and excessive pointer movement potentially causes whiplash! Using both hands to hold the pointer can prevent jitter, which is very distracting for the audience (perhaps revealing your anxiety level or a previous evening's activities).

Don't pace (particularly in circles). If there's a stage, be careful not to step off it inadvertently. If there's a podium, don't assume it to be so well anchored as to support the full weight of a leaning body.

In spite of the best preparations, accidents do happen: a projector jams, a fuse blows, or a jackhammer starts up next door. For such eventualities, immediately try to resolve or request assistance in resolving the problem. Remain pleasant and polite. If a time gap ensues, try relating a suitable anecdote, ask for questions from the audience, or ask about the audience's experience. Most public speakers have a whole library of their disasters. They are not the end of a career nor the world.

There are also rare occasions when you will encounter a hostile questioner. Most people don't like belligerence, so the audience will probably be on your side. It is wise to answer the assertions calmly and concisely. Don't argue but say that there is a difference of opinion and you would be happy to discuss it in detail later.

It's true, there's a lot to remember. But, by working at several points each time you present, you will eventually do them naturally without too much effort. It helps to appreciate that, by and large, the audience is on your side and sympathetic (they likely want to learn something from you and have devoted time in order to do so). In other words, everyone wants your talk to be enjoyable and successful. Some organization, use of standard rules and practice will assist you a great deal in communicating your geophysics.

Summary

Geophysical studies are often presented in a general structure which includes introduction, methods, discussion, and conclusions. The use of standard writing and presentation rules-of-thumb can greatly enhance the impact of your geophysical work.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article