Introduction

“Being employed is one thing; being fully employed and engaged is somewhat more difficult to achieve.”

This paper combines the thoughts derived from conversations with somewhere between 1000 and 1500 people with ideas from David Foot and Daniel Stoffman’s book “Boom, Bust and Echo” to provide an explanation of some of the current industry trends and offer some ideas on what may evolve in the next 5-10 years. By understanding these trends, geophysicists may be able to position themselves better to capitalize on these changes.

Demographics

Foot and Stoffman say that “demographics explain about two thirds of everything”. North American demographics have been skewed from a normal distribution by world events, specifically the Second World War. In an extended spasm of optimism and patriotic fervor beginning shortly after World War II, the citizens of Canada and the US had children at a prolific pace. The manufacturing economies of both countries had thrived through the war years and were positioned to succeed further against their war-ravaged European and Asian competitors. People had good paying, secure jobs in an atmosphere of peace and predictability. Put this together with a lack of convenient, comfortable birth control and voila! – an unprecedented birth rate.

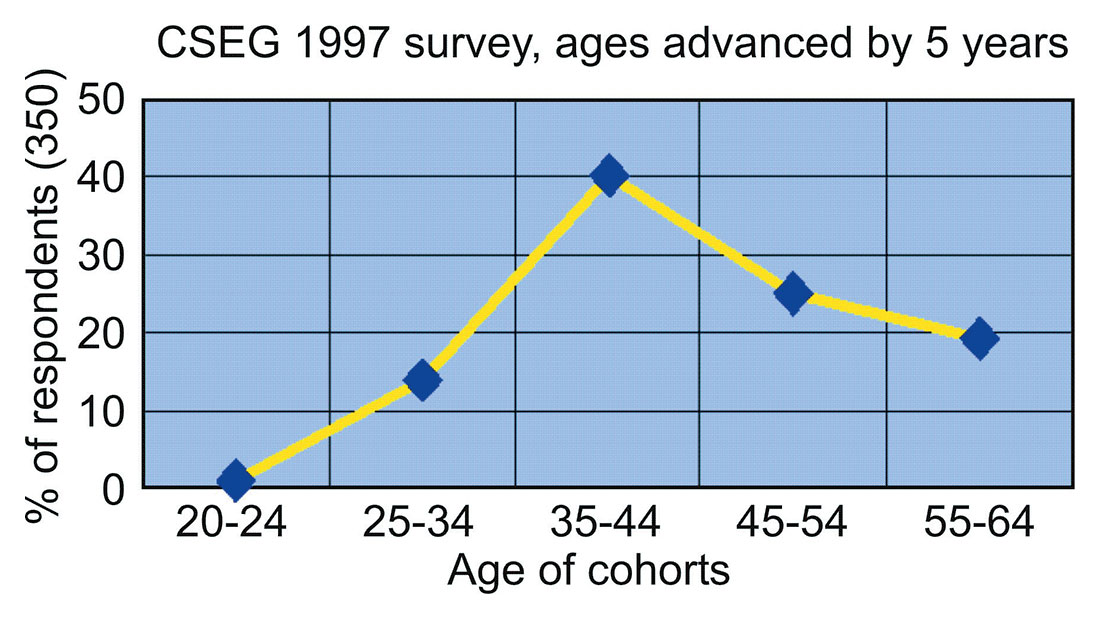

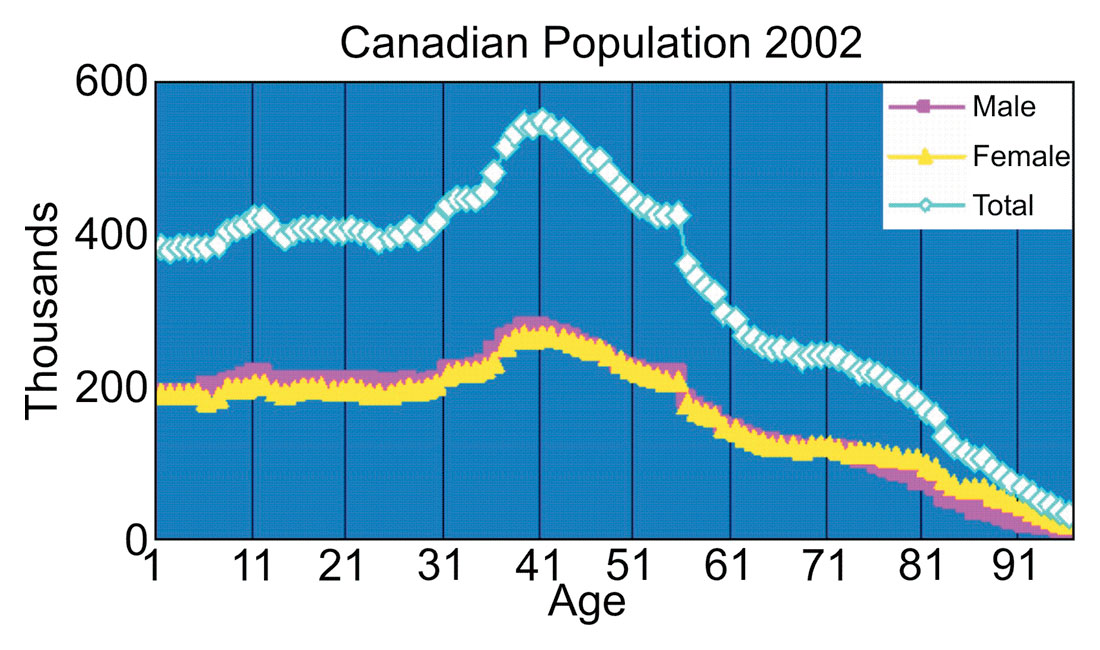

Foot uses the terminology “cohorts” to describe the groups of “Baby Boom”, “Generation X”, “Baby Busters” and “Echo”. The population graph from the 2002 Canadian census (Figure 1) shows us which birth years these cohorts represent. As defined by Foot and Stoffman, the Boomers were between 36 and 55 years old, with Generation X being at the tail end of the boom. The Bust was represented by those 23 to 35 years old and the Echo from ages 7 to 22. There is a distinct bulge associated with people over 40 (this is not solely dietary). These numbers are Canada wide and Calgary may be slightly different demographically, but the general trend is the same – a large group of people around 40 years old who are entering a different phase of their lives. Figure 2 is taken from the last CSEG study done in 1997, aged by 5 years. Because the data were acquired as years of experience and not age, it was assumed that careers started at age 23. This figure points out a potentially worse situation than Canada’s demographics would indicate. There is a pronounced high over 35 and a relative lack of the under 35 crowd. The difference appears to be exacerbated beyond where Canada’s demographics would indicate and there are probably several reasons for this. One is that the oil patch has a bit of an image problem among young people for being a cyclic industry. The second may be that other technological fields such as high tech and biomechanics are drawing off a higher proportion of those with a technical aptitude. A third factor may be a stronger sense of environmental awareness among young people – they may choose another field based partly on their perceptions of the oil industry’s stance on environmentalism. Whatever the reasons, there is a pronounced lack of employees in the lower experience levels.

Foot and Stoffman discuss at length the predictable behaviours of people in each cohort. For boomers older than 40 time becomes more important than money and family responsibilities take on more importance, whether it be soccer and the kids or looking after an aging parent. Typically they are more financially secure, have paid down a lot of their debt and can take more risk. As technical professionals they require less supervision and aspire to more autonomy as they become more experienced and fully confident in their technical skills. The most repeated criteria in the perfect job are:

- A balance between personal and professional life.

- Working for a smaller, active, growing Canadian company with an effective management team/structure.

- Less bureaucracy, more autonomy, a chance to share success via options and to contribute in a substantial way to the company’s success.

Comparison of these desires to the aforementioned predictable behaviours shows how they overlap. So, in a nutshell, the oilpatch boomers are acting statistically very much as Foot and Stoffman would predict.

Current business issues

Let’s wind the clock back to the early 90’s. A VP of Exploration of a growing oil and gas company, looking to add a geophysicist or two, would want a person who was fully trained and competent yet still hungry and motivated to achieve. While hiring technical staff in that magical 5-10 year experience range, it was apparent that there were a lot of professionals with the requisite qualities as all those boomers were in their prime years for that type of opportunity and were also seeking greater financial security. So the Renaissances, POCOs, CNRLs etc. had substantial available expertise at the right point in their corporate growth to help them succeed and the boomers got a taste of the perfect job.

Contrast that to the current demographic situation. A VP of Exploration in an oil and gas company today would find a lot of his potential hires having a different set of priorities from 10 years ago. They are certainly not in the 5-10 year experience range; in fact, few people are. Does the current business model of growth to a modest size and sale/conversion to a trust vehicle partially reflect a limited supply of talent? It may not be solely responsible but it may play a part. If a company is unable to attract the personnel necessary to generate opportunities, it will be very difficult to grow. What might be the implications of a lack of professionals in the 5-10 years range – the “Bust”?

- This is good news for those in that cohort – supply/demand is in their favour.

- It is difficult for companies to grow with younger staff.

- Do they need a different business model to compete for talent? – Lifestyle vs sweatshop?

Several things have changed in our industry but the most significant are:

- 1. The emergence of trusts.

- The influence of the multi-national and large producers.

- The proliferation of startups.

So pity the poor boomers. Having ridden this wave of affluence through the ‘90s and putting their hard earned dollars into high yield mutual funds, the new millennium dealt a couple of body blows. Those investments went in the wrong direction and retirement looks a bit more distant. Since the merger of their mid-sized, publicly traded Canadian company into a larger one, they do not have the same autonomy and responsibility that they had before. What are the options now for achieving job satisfaction? Perhaps a managerial role would satisfy the urge to contribute more but there is a lot of competition from all those other boomers.

The stratification of the standard E&P industry into multinationals at the high end and startups to 3000 BOE/day at the low end, with very few Canadian exploration companies in between, means that those who aspire to “the perfect job” have few options. There is still a substantial group of small, publicly traded Canadian companies that represent, surficially at least, the most direct route to the “perfect job”. Unfortunately, their growth seems limited by the competition from trusts and lack of investor support. There are still opportunities to be had within this group but, as yet, they are unable to absorb a substantial amount of the “pent-up attrition” that is out there.

The larger companies still have a lot to offer the senior professional: good compensation programs, lifestyle advantages and support. Unfortunately the decision-making process is often slow and a professional’s connection to the bottom line may seem a bit distant. Some companies do a reasonably good job of passing authority down the chain far enough to be effective but that is the exception rather than the rule. As well, a significant proportion of their cash flow is redirected to frontiers and international opportunities. Back in 1997, when the Renaissances, POCOs and Crestars were in their growth stages, high oil prices and only average gas prices meant a very active seismic industry, since there was nowhere else to spend the cash flow. If they were around today, the industry would be hopping.

The trust companies are partially filling the gap that was previously the domain of the publicly traded Canadian company. They provide many of the factors that boomers value beyond company size alone. They typically run lean organizations and have fewer management layers and less bureaucracy in order to maximize disbursements. They offer units as long term incentives which are lower risk than stock options but are taxed differently. Perhaps most important for geologists and geophysicists is the nature of the work, which focusses on low risk drilling while minimizing exploration expenses such as new seismic programs. Because they do not qualify for CE and E credits, dry holes have immediate bottom line impact. Barring legislative change, trusts are here to stay. In a high price environment and assuming an ongoing source of properties to produce, they should continue to thrive. They should also benefit from the increasing conservatism of the boomers, who change their investment strategies from capital accretion to preservation as they approach retirement.

Also in the same company size (at least their Canadian branches) are many American companies that have gained a presence here through acquisitions. This group includes Calpine Canada, Tom Brown Resources, Dominion Exploration Canada and others. Do these represent opportunities for the boomer? On the plus side, they are typically active and attempting to grow operations in Canada. Most offer a lifestyle balance, good base compensation and good bonus programs. Stock options are not the norm, however, and because these companies are typically part of larger organizations, employees can feel distant from the company’s success or failure . Spending authority varies considerably among them, with some requiring direction from head office for expenditures that appear relatively small.

So, if the trust companies are not to your liking, the intermediate US companies don’t offer the upside you’re looking for and your current employer doesn’t give you job satisfaction, what choice do you have? Enter the startup and a chance to contribute in a big way to the company’s success or failure and capture upside through options or taking an ownership position. Autonomy is yours since you are the exploration department. Effective management and a fun environment is very much in your control; who you team up with and how you work together is key. Lifestyle and balance is the issue most difficult to control. Despite the ownership position you hold, there are still shareholders to satisfy who still expect return from their investments. In the startup scenario, the management team has both the responsibility for generating the strategy and the spending authority to implement it.

In the current demographic environment, is the proliferation of startups a result of the boomers seeking the “perfect job”? It could play a major part since it potentially meets many of the boomers’ needs. How many will survive? Only time will tell but this is not necessarily the best time to be a startup. High commodity prices are a significant blessing to any producer and startups are no exception. Competition at the startup level is significant though, both for seed capital and, once established, for acquisitions of land and properties. Coupled with the trusts’ competitive advantage for acquisitions, it presents a challenging environment to commence operations. Oil and gas companies typically grow by any of three means – exploration, development and acquisition. If it is difficult to compete for acquisitions and pool sizes are shrinking, thereby lessening development opportunities, then exploration is the best vehicle for growth. Unfortunately this strategy is difficult to predict.

If these are the realities of each option, you as a professional must understand yourself and your situation. Your hierarchy of needs will dictate which of these represents an opportunity for you. Most of us work to provide security for ourselves and our loved ones and would choose to be employed less optimally, while providing for our families, rather than waiting for the perfect situation. So what might the future hold and what will be the impact on different company styles?

Looking to the Future

In general, oil prices are difficult to predict because world oil price is volatile and supply is abundant so let us assume historical averages. Prevailing wisdom seems to be that gas prices will stay well above historic averages for the foreseeable future. WCSB gas pools are getting smaller and declining faster. In a market that is essentially North American, supply and demand should be relatively predictable. The most likely impact on the supply side is northern gas, from Prudeau Bay or the Mackenzie Delta, but it is probably at least 5 years before production comes onstream. On the demand side, a major downturn in either oil prices or the US economy could bring about a substantial drop in gas demand. Let’s consider the high gas price scenario first.

Continued high gas pricing should lead to several things:

- High drilling activity for all sizes of companies.

- High netbacks. This is good news for trusts and their unit holders and for other producers.

- A continued challenging environment for startups and juniors. Acquisition prices are high and trusts are supported by market.

- Continued difficulty for publicly traded E&P companies. The market pays for the expectancy of high prices and hedges are not valued.

- A flat seismic service sector in WCSB. The cash flow generated is being spent outside the basin or paid out in distributions.

High prices are generally a good thing for our industry. In a cyclic industry, the ups are more fun than the downs. However, for the long term health of the industry, what we really need is a good downturn in pricing. Heresy you say…let’s think about the possibilities:

- Lower cash flows, leading to significant property divestments and layoffs.

- Trusts pay lower disbursements and do not attract as much capital.

- Public markets re-invest in E&P companies, giving a potential upside on pricing.

- Startups/juniors are able to make acquisitions at reasonable price, thereby fuelling growth. 5. Capital is raised and spent on exploration activity in Canada.

Ultimately, once investment returns to the junior public markets, exploration spending will rise, thus leading to greater seismic activity levels. Our industry has always been cyclic. With each cycle the numbers of people employed gets a little smaller as some get disillusioned and go into other fields. The above predictions may work out, maybe not. Your company may be around in 6 months, maybe not. What are the strategies for getting that next job in an industry that is constantly in flux?

When you are out on the street, after being downsized, rightsized, re-organized, re-engineered, severed with cause or without, punted, fired, laid off or turfed or maybe even if you just quit, you may have to find new employment at some time. There are three things that you need to have done to maximize your opportunities when you hit the streets:

- Be technically driven and retain your enthusiasm for your discipline. Love the work, not the job.

- Deal with people with honesty and integrity.

- Think like a landman.

Point one is pretty clear. If you don’t care about what you’re doing, people will recognize it and your lack of success will reflect it. Points two and three go together. Your reputation is key and when you apply for a job, it will be a blessing or a curse. Calgary’s oil patch is, in essence, a small town and most of what happens is within ten square blocks where everybody knows everybody else. Think like a landman. No, not spending your afternoons on the phone or the golf course after returning from a two hour lunch. Did you ever wonder what makes a landman successful? It’s being able to get the deal that no one else could, the farmout or the prized acreage. Why are some successful? Because they spend their days building relationships of trust. Business is based on trust and without it, it’s very difficult to close a deal.

The job search needs to be looked at in the same terms. The whole process of resumes and interviews is meant to achieve a level of trust. Build relationships of trust and the opportunities will be there. Keep your network strong, not just contacts, but relationships. The time you spend in building and maintaining a contact base will pay off in spades next time you’re forced to look for work.

Conclusions

There will still be a viable oil and gas industry for the foreseeable future. It’s up to each individual to understand his or her hierarchy of needs in order to recognize an opportunity and not just another job. The industry will continue to change due to market forces but will also be shaped by demographics. Startups growing to 2000-3000 BOED will continue to be viable models, as trusts will require replenishing of their production base. Trusts will continue to grow and multinationals will dominate the total industry production as long as commodity prices remain strong. Publicly traded Canadian companies will continue to struggle to attract both capital and the 10-15 year professionals, who will have a ready market for their expertise. As the workforce ages and desires more time and flexibility, contracting will become even more prevalent. Because of retirement plans being set back by the negative returns of the last few years, people will have to work longer in order to retire but will still seek a balance between work and family. Best of all, junior geoscientists will finally be in demand!

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the 2003 CSEG/CSPG convention. With rapid changes in the resource industry, some of the companies’ information is already out of date.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article