Tad Ulrych is a well-known geophysicist who is particularly recognized for his work on geophysical signal analysis and inverse theory. Tad became Professor of Geophysics at the University of British Columbia in 1965 and an Emeritus Professor of Geophysics at UBC in 2001. Tad has been a mentor to several generations of students, many of who are now known in their own right and occupying prominent positions in the geophysical community.

Tad has served as a member of the SEG Translations Committee and the editor of the Journal of Seismic Exploration. For his distinguished contributions to geophysics, the SEG honoured him with the Honorary Membership Award in 2004.

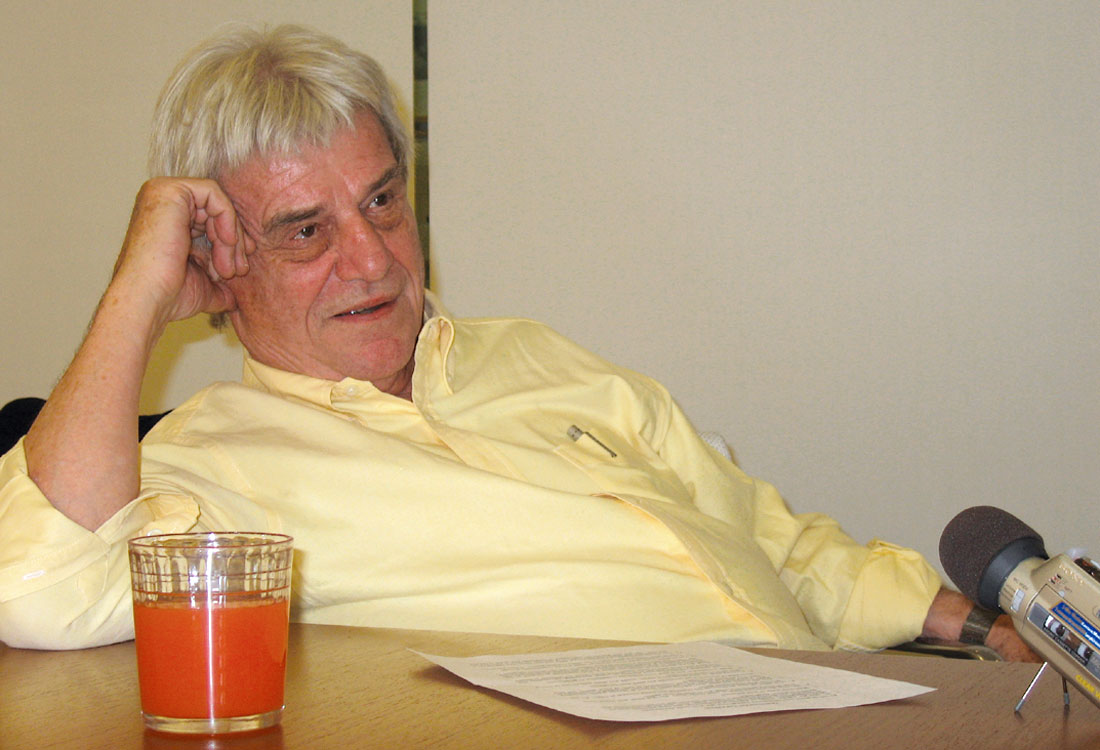

Tad was in Calgary as SEG Distinguished Lecturer to deliver his CSEG luncheon talk on ‘The role of amplitude and phase in processing and inversion‘, and we grabbed the opportunity to interview him. His infectious humour and enthusiasm are noteworthy traits that endear him to people. Following are excerpts from the interview.

Tad, let’s begin by asking you about your educational background and your work experience.

I began learning English when I was about 10 years old, in Cyprus. That was in fact my first schooling experience, because prior to that, you know, we escaped from the Germans then from the Russians. My parents did the best they could to educate me at home. After three years in Cyprus, we arrived in England where, after some years of forgettable schooling at the hands of Benedictine monks, and a few more years of unforgettable university schooling, I graduated as an Electrical Engineer from London University. My first job was working in London for a company specializing in ultrasonics. I realized very quickly that I was going to be earning 7 pounds a week and then 7.50 and then 8.00 pounds a week and that’s where I would be for the rest of my life, so I found an opportunity to come to Canada and work for Westinghouse Electric. And when I got to Canada, the job had disappeared because there was a recession. All other jobs in my field required security clearance but I had no citizenship. I was stateless, a DP in fact. In my daily and discouraging job search in Toronto, I happened to be walking past a building, which said 49 St. George Street with a big sign, Geophysics. I had no idea what that was but I entered and met Don Russell who gave me my first Canadian job, building mass spectrometers. I continued job hunting and was, finally, rewarded with an offer from Northern Electric in Montreal to work on the Avro Arrow, for some huge amount of money, like four hundred bucks a week. Two weeks before I was supposed to join Northern Electric, Diefenbaker cancelled the project. I returned with hat in hand to Don Russell, under whose expert guidance I completed a M.Sc. and Ph.D. at UBC in Vancouver.

And your work experience? You have been teaching in British Columbia only?

No, actually prior to getting my Ph.D. I was a Prof. at the University of Western Ontario, which I liked very, very much as a University didn’t care for the town. I got a postdoctoral fellowship in Oxford and then the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa. From there I got a job at UBC.

When was that?

That was in 1965. A year after arriving at UBC, wonderful Jack Jacobs, at that time the Head of the Institute of Geophysics in the Physics Department, knowing how broke I was, came into my office and said there is a job for you at three times the salary to teach in Brazil. And I said, but Jack, I have been here only one year… He said just go, it’s okay. And so then I started teaching in Brazil where I taught afterwards off and on, 1984, 1987, I guess about four years in all. I have also done some teaching at the University of Kyoto. I worked in Tokyo for seven months for the Japan National Oil Company and that’s about it.

So that’s your Japanese connection there?

That is my Japanese connection with my wonderful friend Toshifumi Matsuoka who actually worked with me at UBC from 1982 to ‘85.

You got a B.Sc. in Electrical Engineering and then switched over to physics/geophysics, studying isotopes. Were you always interested in science or was it a natural progression from Electrical Engineering?

No. Actually when I was in London I tried to get a scholarship from a Polish Foundation to study languages, but they only had scholarships for science so I chose Electrical Engineering.

Well it has turned out to be really beneficial to you and it’s a very good life you have led. Who were some of your mentors?

Well, when I was going to University in England there was a wonderful man called Dr. Geary and he taught me how to think, essentially. He was a Physicist and he taught Statics and Dynamics. He would say, imagine a problem and then think about the problem, not the usual, here is an example, do it. He was wonderful. There was another Prof., Mr. Chellingsworth, who also was always trying to get us into the thinking process. My true mentor was my Ph.D. supervisor Don Russell who was phenomenal. He was an encouraging, intuitively brilliant, humble, inspiring, and wonderful man. Also Jack Jacobs who is unfortunately no longer with us, but he also gave me enormous encouragement always to go and do the stuff I like, wonderful people. And then, since I started in this marvelous field of ours following my sojourn in lead isotopes, I have been so honoured by having mentors like Tury Taner and Enders Robinson and Sven Treitel, I mean those articles written by Robinson and Treitel made me think I understood the stuff . Phenomenal!

Arthur Weglein, who taught me so much, Genia Landa of course; Jon Claerbout whose books inspired me so; Jon Claerbout always taught me, because I read his books. Learning by yourself from the books of others is one type of learning. And then there is learning through the touch of others, like Tury, Enders, Sven, Arthur, Genia, you meet them, talk to them, they become your friends and inspire you to heights.

How do you look back your career now? Do you think you would have done anything differently, were you to start all over again?

You know, life is an adventure! Life is some kind of a weird, stochastic process and I will give you an example. When I finished my Masters I didn’t want to do a Ph.D. My Dad was sick, I just wanted to go and earn some money and I applied to various places. I didn’t get replies. Don suggested I apply for a scholarship just in case. So I did and I got one. And then when I didn’t hear anything back I started doing my Ph.D.

About 5 years ago I met the man who had been the director of the Bedford Institute of Oceanography where I had applied after my Masters. And he said to me something like – we found your letter three years after you had sent it. It was sort of buried under stacks of you know what. If they had not lost my letter, I would have got the job, and then my career would have been totally and utterly different. All I can tell you is that I am so happy, so honoured, so humbled, so delighted with my career and what I have been able to do, that if I had had to do it again, I would do exactly this.

You spent all your professional life teaching and doing research at UBC, more or less, tell us about some of the experiences that you would like to share with others now.

Well, one experience was the first class I taught when I came back from South Africa. I had to teach a fourth year class in Applied Geophysics and I thought, no problem, I mean a little magnetics, a little gravity, refraction and it’s finished. Then I opened Geophysics, auto correlation, convolution, minimum phase - I didn’t know what the hell that was all about! So I said in class, I have one advantage over you. I don’t have to take classes, you have to take six, I have to give just one. I am going to keep one class ahead of you guys. It was phenomenal. They were such a talented bunch, people like John Samson and Dick Pelletier; it was just a phenomenal class and I think they could see that I was teaching them what I was learning with love and passion myself and it went super well. So I think the thing is if you teach, do it with passion. I mean really, do it with humility and do it with truth. Professors have an extraordinary power, particularly in the eyes of young students who somehow feel that, you know, they are a sort of parental continuation, I think we have to take that into consideration, recognize what we don’t know and admit to it. Truth sets one free. That’s it.

And another thing that I consider fundamental – when my daughter was going to the University of B.C., she said to me, look Dad I don’t want to do the garbage you are doing, math and crap like that, I want to do a general degree. I don’t want to go to University to prepare myself for a job; I want to prepare myself for life. I thought that was a very clever idea. And Lyza asked me, “What courses do I take?” I said it doesn’t matter; it’s who teaches that matters.

Anything that catches your fancy, go ahead and do it...

Go ahead and do it. Go ahead and do it, but make sure that the person who is teaching that course is great and so her mum and I helped her, because we were both at the University. Her mum knew a lot of people there who were also teaching part time and stuff and I think Lyza had a phenomenal time because she went to hear lectures from people who not only .had something to say, but also knew how to say it.

Tad, you are a well traveled man, you have traveled to different places for many years; you mentioned the Federal University of Bahia, University of Kyoto and University of Pau. Could you tell us about your experiences in each of these places and how are they were different from the UBC experience?

Well, Japan is as different from Canada as I am sure Calcutta is different from Calgary. I love UBC. UBC has treated me extraordinarily well. They have respected the fact that I would be the worst administrator in the world and left me alone. You know, I think financially one must suffer a little at that decision, but I don’t care. They put me on wonderful committees like Equity and Gender, which met once a year and you came in and said, “Anybody not equitable? Good bye.” Really great.

I love Japan. I don’t know why I love Japan; I guess I love their breadth of imagination and the smallness and tidiness of their lanes. There is such a wonderful feeling when you get off big Karamachi, and you find these beautiful little tiny alleys all decorated in bamboo and everything is on my scale. I feel infinitely more comfortable in a place that’s my scale than I do in a place like Dallas or Houston where if you don’t have a car you die. I am sure that I was Japanese before I was a Pole. I am also drawn by the fact that the Japanese are not religious. Very spiritual, but without that frightening Western religious zeal. Japan has so much character, so much colour, and happiness, music you know. One other thing. Japan came out of the Edo period. Isolation. The Japanese began to absorb other cultures, particularly American of course. But so cleverly, not full-band, band-limited. Cut out the low and high frequency noise, the aggression, crime and drugs. The young people are so beautiful, colourful and happy. I just love traveling. I have had wonderful experiences in many different countries.

What kind of research work interested you more than the others, because you have focused in on certain areas?

What happened essentially was that when I was doing lead isotopes I liked it very much, I had a wonderful supervisor as I mentioned and I was quite happy in that field. I did find however that 95% of the time you spent preparing to obtain the results while 5% of the time interpreting. I found that rather unsatisfactory although I did like the experimental part, the chemistry, the electronics and so forth. Then one day I went to the AGU to give a paper on some preposterous subject that I actually published in Nature, and I was so happy, so proud you know, young Prof., paper in Nature is going to make a real impact on the world. At that time AGU had all sorts of meetings in one session. So I walked into where my session was going to be, this guy was talking to an audience of 120 on convolutional filters, I will never forget that. So I sat and I listened, and I liked what he was saying about convolutional filters. Interesting, a little bit like my old field, electrical engineering. And then when he finished, the Chairman asked for questions etc., and then said now, Dr. Ulrych will present a paper …and 118 people got up and left and I thought – time to find a new field.

When I was in Brazil in ‘67, I was teaching a course on potential fields and decided to digitize all the manually performed filtering techniques and the interpretation. I simply just fell in love with it. It’s the idea of here is what we have recorded on the surface, and we are trying to understand where it came from and the informational content of this stuff. Very intriguing.

Now looking back on your geophysical career, would you like to share with us one or two of your exciting successes?

Well, I loved homomorphic deconvolution because it is so nonlinear and nobody was doing it. I didn’t like the fact that noise essentially killed it and I wasn’t at that time well versed in anything to understand how one could get around it. But I feel, how can I say it, there are some things I think that sort of project you a little beyond where you thought you were, and homomorphic deconvolution did a little of that. Then a real change in my life happened when I went to a meeting in Philadelphia and I heard John Burg. I understood virtually not a word. He coupled maximum entropy with prediction filters, Toeplitz matrices. I had no idea what he was talking about, but he gave out a piece of paper with a few details and I programmed the technique, probably the most inefficient program ever written, but it worked. I started working in this field, wrote a couple of papers and a particular one with Tom Bishop on maximum entropy and autoregressive modeling which led to a significant upward leap, if you like, in my care e r. Very lucky, that that Philadelphia meeting occurred. I was in the right place at the right time. If you go into maximum entropy now you would be one of two zillion, but I was sort of one of five or something, and so it was spectacular.

And then the next thing was when in 1984 I was invited by Carlos Diaz to go to Brazil to teach. Carlos Diaz is an extraordinary man; I mean the guy is incredible. He found these notes I made when I was in Bahia in ‘67 and asked me to come, and there I essentially met those who you have to meet in order to pretend to be one of them. Everybody went t h rough there , Jacob Fokkema, Sven Treitel , Enders Robinson Arthur Weglein, Sergei Goldin, I mean Wolfe Massell, Paul Stoffa, Peter Hubral, who have I missed? And that gave me this thing, you know, like my God, I know Arthur Weglein, we can joke together, so that was a huge upper in my self confidence. I really, really loved that and you know the other huge thing is, when you have students like Mauricio Sacchi, Daniel Trad, Scott Leany, Bill Nickerson, Danillo Velis, Ken Matson, Kris Innanen, Sam Kaplan, I cannot mention them all, I mean you don’t need anything else…these people are so fine, and you pretend to yourself that you are their supervisor, yes on paper for sure.

Do you consider the work on homomorphic deconvolution as the most important contribution or have you...

No, I think the most important contribution of mine was my involvement in maximum entropy. I think when Tom Bishop and I coupled maximum entropy with auto regression and Akaike that paper got more hits than anything else I wrote. I mean homomorphic deconvolution I think gets hits from people who want to have a joke but this paper really got hits because maximum entropy needed at that time an understanding of how many coefficients are required in the filter. That was big and really, I think is a main contribution.

And then I did some other little things like bringing together ARMA models and Pisarenko with Rob Clayton, and that has found favour with those who like this kind of stuff. And then recently the most exiting thing without a doubt is the work that I did with Mauricio Sacchi on the sparse Radon transform. I mean if Maurice and I had patented this thing we would be millionaires because it is used all over the industry. This was essentially Mauricio’s Ph.D. so it’s mostly his work but I think our joint effort in that is for me one of the most important things.

Your research efforts have focused on signal processing, information and inverse theory. Could you tell us in a general sense about the different problems you have tackled?

Well, you know my interest in all of this is not to construct some huge program. My interest is in part, philosophical. What are the concepts? What ideas can one extract that may lead to something important, and then, of course, what needs to be done to make things really work. So I think that for me the idea of Bayesian inference, sparseness, entropy, information (but particularly Bayes since, as Alberto Malinverno showed, Bayesian solutions are sparse), form the main building blocks of my research. I am now very interested in joint inversion. How can we combine seismics with other data, maybe through projection onto convex sets, or something of that nature. Perhaps marrying all in a sparse manner to understand better and better what we are really after which is the physics of the reservoir. Well you know a lot more about that than I do, but just look at the scale structure of this problem, the complexity of it all. Slow waves, fast waves, medium waves, heterogeneous, anisotropic. So it is very tough but very fascinating. Signal processing is great, I love it. Inversion is great, but essentially what you want to do is the physics of it. For me now, processing has become a kind of a puzzle. How can I do this noise attenuation so that, in the signal band, the noise is as small as possible? Band pass filtering is not it. It is very difficult and very important. Inversion is always an underdetermined problem. We must impose our personal beliefs via constraints. These must be physically motivated. Understanding the physics is, of course the central issue. I am not sure I can ever do anything to further our quest, but I mean to try.

Tad, in your opinion, what are the directions in which the future R&D of our industry world-wide is focused, and what is your impression about the development that people can expect in geophysics in the near future; any path breaking technology that we can expect, like the 3D technology that caught on in a big way in the early ‘90s? Would you have some opinion on that?

We spend most of our time looking at an equation that says, “This is what we measure, this is what we would like and this last term is ‘noise’”. We then operate on our measurements in some very complex nonlinear manner and hope. But what about the noise? Oh, easy, Gaussian, white and uncorrelated with signal, i.e. we have no information. I think we have to understand noise, and we have to understand noise in a profound way. People are now passively listening to the earth. It is giving us a wonderful opportunity, I think, to understand what the earth is like passively so that when we hit it and it responds we can at least know something about non-signal generated noise. So I am very interested in that, very interested in trying to understand the nature of noise. And I think that we could do this. However, the thing is that oil is a hundred bucks a barrel and there is not too much incentive in the industry now to do this kind of research. Well, in my opinion, although this attitude doesn’t affect me too much, my advice is pay attention to noise, pay attention to phase, pay attention to new concepts because, surely, the time will come when they will be required. In any case, otherwise life gets boring. I was talking with my great friend Daniel Trad who has done probably the best work in the industry for Veritas on interpolation and extrapolation with the great help of Mauricio Sacchi. He said to me, “You know Tad, I am bored.” Not of course that he will do less good work for his company, not in a million years, but I asked why is he bored? He said, “Because all I am doing essentially is to make this very complicated code user- friendly.” That is about as interesting as polishing a car.

He probably is interested in something new.

Oh yes, and he is so bright and so inventive that he wants to go into something like, well he is talking about quantum physics in another interesting way. And so, that’s the trouble when the industry is so successful – when the industry is not successful then people kind of sit down and think; when people are very successful all they want to do is process as much as possible and find as much as possible and maybe not enough time is devoted to preparation for a leaner time, which will come sooner or later.

So that raises an interesting question: with the high price of oil, the companies may not feel the need to do very extensive exploration, they would probably go ahead as you just said, just go ahead and drill here and there; so do you think our research efforts will suffer with the high price of oil which is expected to continue to rise in the near future?

Unless people have vision I think. There are some companies, which I find impressive, like Aramco, with the exciting Panos Kelamis group, because they are always trying to come up with new ways to do things, and they devote funds and personnel to the development of tools to develop new areas, areas with a special character. So they need that technology for their own behalf and they are interested in that. I don’t know many other companies that do this but this may be because of my lack of experience, I mean how much research is being done in big companies? When I talk to people in the industry, such clever people, they say, “Ah, man, that’s so interesting, I wish I had time to do that.”

Well, in the private companies the research is being done at their own pace, in their own way; the basic research we used to have earlier in companies like Amoco is gone now. It is a different scenario now, but whatever little is being done with the high price of the oil, that might suffer.

Well, you know, just as you say, you made a perfect point. In the old days we had Amoco with a group lead, of course, by Sven. Can you imagine this industry if there had not been that opportunity to do the work they did? We would be witching for oil with a crowbar.

Anyhow, that was an interesting phase that our research went through. You have published one book and written many research papers. Would you like to share with us some of your writing experiences?

Writing experiences? The most pleasant writing experience I ever had was when Satinder Chopra asked me to write my memoir – it’s true! I loved it. You asked me once, you asked me twice, I became embarrassed, went to bed, woke up at three o’clock in the morning after thinking about it and started writing and it just flowed out of me, just flowed. I think that I have a talent of getting passionate and when I get into that space it just flows, you know. I get into another space and I can’t think of how to put three words together but when you are in that mood, when the mood effects how you are going to write it just comes out. The painters must have that, musicians must have that you know. You hear something in your brain and then you grab a violin and do it. Not I, unfortunately. So that was great.

I loved writing the book with Maurice because we finally did it. I was in Japan, he was in Delft and we said “now or never”, and now we have something with a hard cover, perhaps even useful. I like writing, I like writing a lot, and particularly in a hybrid style, like a paper I wrote for Geophysics as a tribute to Enders. Of course some science, but also something personal, about ideas and people. Presenting papers is also great, but again, with a certain style. When you go to the SEG, and you have 20 – 25 minutes and you spend 20 minutes showing 47 equations, and walk off, you have accomplished nothing, but if in the 20 minutes you show one equation, a few striking slides and 4 well correlated jokes and make people laugh they will remember the one equation which you were trying to emphasize.

A certain measure of humour.

Humour, of course and not this kind of preoccupation of showing people how clever you are because you can write the triple integral. My good friend Rosemary Knight, when giving a seminar, would put a slide up and it was blank except for a long bracket and it said, 47 very complicated equations. And now let’s talk about the physics.

Tad this is a question that came to my mind when I looked at the title of your Distinguished Lecture, “The role of amplitude and phase in processing and inversion”. For Q estimation, at least in my opinion, we are still not at a stage where you can confidently say yes, this is the Q estimation that I have done, it is accurate, I am happy with it, I am going to apply this on the data. So, given this scenario, what some practitioners are doing for example in AVO analysis, they don’t apply the Q for the amplitude correction but only for the phase correction. So I wanted to get you to say something about that. What in your opinion is the state of the art now; can we expect something more in this area, or what?

I think the trouble with Q is that Q is made of two parts – Intrinsic Q which is basically what we really care about for understanding the reservoir, and extrinsic Q. But we don’t know how to differentiate between the two. We must, somehow, try to get a measure of what is the intrinsic Q and then we could do both corrections, for attenuation and dispersion. I did not actually realize that people will only do the dispersive part rather than the attenuative part because they don’t want to muck up the amplitude.

My very talented graduate student, Changjun Zhang, is doing his Ph.D. on Q and one of the issues that he is trying to tackle is the recognition of what is intrinsic and what is extrinsic Q. It is a very difficult topic, but a very important one.

I am going to say something that is very biased and it is very biased because it is from the work of Changjun Zhang and Tad Ulrych. We published a paper last year on estimating Q using a method Changjun invented for his Masters, which is not based on speculation but is based on the frequency shift associated with the amplitude spectrum. We then use sparseness to try and estimate and remove Q. Tury and Sven have also developed a very elegant Q estimation and attenuation approach. So perhaps we are getting a little closer.

Well I should catch up with this work on Q that you are talking about.

Well, it’s just a different approach. What I like about it is that when one removes Q, using a good Q estimate let’s say, using most conventional approaches, owing to high susceptibility to noise, results are prone to blowing up. The sparse approach is more robust.

What is your impression about the current state of the Canadian universities, in general and then with respect to Geophysics in particular? How do they compare with other North American Universities and European Universities? Perhaps you could tell us in terms of any problems with oriented research, funding, or the abundance or dearth of students?

Oh, you know, my experience is so UBC based. We had a tremendously strong Geophysics and Astronomy group. We had a very active Dean who decided for reasons best known to himself to divorce us and send the astronomers off to join the radio people in Physics and to marry us with geologists, essentially. He did a favor to the astronomers but not to us, because the Physics department has become Physics and Astronomy while we have been submerged into Earth and Ocean Sciences, fewer people will hear about us etc. etc. I have just visited Edmonton, Winnipeg, Saskatoon and I found Geophysics there to be strong and healthy. A lot of active people. Funding is I guess what NSERC can manage. They do as well as they can but there is a lot of demand. I think that at UBC, when we now have fewer geophysicists on faculty and a lot of geologists, obviously the funding is different than in the past. UBC also apparently is quite broke, but these are things I know nothing about. Perhaps universities are like restaurants. One owner manages the business very well, and then someone else buys it, goes bankrupt, someone else comes in, changes the menu and it works. Universities prepared one for living life as fully as possible. Now it seems that they prepare one for a specific job, and those who have that task are asked to generate as much cash as possible. I apologize, I am rambling.

In any case, everywhere I went I was impressed by the solid camaraderie inside the geophysical groups. I mean, whether they are doing global seismology or applied seismology, mining geophysics or studying core dynamics, the feeling is of a geophysical bonding. We are not the poor cousins to physicists. Our field has it all – Physics, Chemistry, Engineering, Geology, Mathematics, forward and inverse problems. I always try to point out to students how lucky they really are to be in this field. I mean, what would you rather do? Study neutrons? You can’t even see the damn thing. I mean, have you ever heard of anyone drilling a neutron. Of course, I am being facetious, but I do find the “lack of purity” argument annoying. So all right, we don’t go out there and look at the big bang, but does that make us less imaginative? I believe in fact, that in every field of endeavour, when people do inversion, at some point that inversion has roots in geophysics. Perhaps I am wrong, but as far as I am concerned, the first person to solve the problem of one equation with two unknowns, usefully, was Enders Robinson.

Do you have enough students at UBC every year?

You mean me personally?

No, in your Department.

Our Department is undergoing a change. Garry Clarke, brilliant glacierologist, is retired. He is keeping on but I am not sure of his plans. Ron Close, Mr. Lithoprobe is retired, Doug Oldenburg, who has transformed the mining industry in B.C., is half–time. I am retired although I have three Ph.D. students. I think it’s okay, but I am not sure because, you know, it’s not like six young Profs looking for good graduate students. Michael Bostock is always looking for good people, so is Felix Herrmann, but I have been traveling a lot and have simply lost touch with departmental details.

Good, you have a sort of a balance. So, in your opinion, what sets the UBC apart from other Universities?

The beauty of the location of the campus.

Okay, apart from that?

When you say, “sets it apart” that suggests that it is sort of better or something, does it?

Well, in a way yes. I mean how do you attract students? Why should students go to UBC and not to Saskatchewan or Calgary or somewhere?

Yes, we attract students; well I am not involved with this anymore, you know, I mean this question would be much better answered by people like Michael or Felix or Elizabeth Hearn who are involved in this kind of thing, but I think, we have a fine group, but not in any way superior to that at the University of Alberta. Their amplitude is great. Their phase suffers, location. The Alberta group is very active, marvelous people with a strong connection to physics. I mean it’s just booming. Just look at the work Mauricio Sacchi and his students are doing. I like the University of Saskatoon with an exciting group and the Universities of Winnipeg and Calgary. I do not think that UBC is superior to these places by any means.

Wooil Moon at the University of Manitoba said to me, “Thank you Tad for coming, thank you Tad for coming.” I said, “Oh Wooil, shut up for God’s sake! What is all this thank you?” He said, “Well, you know, from UBC to U. of T., and the stuff in between is fly-over.” I said, “Well, not fair, it’s just not fair.” I mean why fly-over? I found in not flying-over just how much exciting work is going on. When you go to an art gallery where there are a few well-known artists represented, it does not imply that the rest of the pieces are reproductions. No, I don’t think anything sets us apart. We do have some very good people in a beautiful setting. Other places have excellent people also, maybe not such beautiful settings and the weather is bloody terrible. I mean it can be a killer, as you well know.

But, I mean, look at the University of Calgary. Larry Lines, Brian Russell, Gary Margrave, John Bancroft, just to name a few, so what are we talking about here?

What I meant was, like University of Calgary is known for applied research, U of S is more into structural seismology work that Zoli has been doing, UBC in my opinion is more into inversion, which is the work you and Doug Oldenberg have been doing, or the work on Lithoprobe that Ron Clowes has been doing. So from the field of research that the faculty members are involved in, one can guess the type of work that the students can expect to do.

Well, I think right now it would be like this – do you want to do absolutely first-rate gravity, magnetics and EM in Canada? Do it with Doug Oldenburg.

If you want to do absolutely first rate global seismology concentrating on subduction zones, tectonics and state of the art thought, that kind of stuff, see Michael Bostock.

If you want to do first rate seismic processing and inversion using curvelets and sparse sampling – go to Felix.

If you want to try to do some totally kooky, off the wall research that could become important but is always fun, try to get Ulrych if you can, because he doesn’t have too much money.

But, on the other hand, if you want to do any kind of processing and state of the art inversion and beyond, in any dimension on any scale with ideas about everything else, go and see Mauricio Sacchi in Alberta. He will set you apart. As will so many other people in other places.

Tell us about some of your other interests apart from the science that you practice.

Well, I used to absolutely adore skiing, so much so that some years back I got fed up teaching and I arranged it so that I did all my teaching in the first part and then in February I took off for Colorado, pretending that I was going to do some extraordinary research at the World Wide Seismic Web, or something like that. I ended up locking myself for fourteen days in a motel in Boulder, and wrote a paper on maximum entropy that changed my scientific life. I then went up to Aspen where my brother had a restaurant, waited tables for thirty nights, skied during the day and I loved it. I love traveling, I love music, I love playing tennis and pool. Pool is easier. Tennis requires partners who are good. The problem is that they always turn out to be better than me so they get bored. I love reading, and I am an obsessive buyer of science books, which I never read.

Good collection, one day you might read them if you have time.

Yes, true, but I so enjoy traveling around and meeting people like you, interesting and wonderful people to talk to, that I don’t think that I will have time. I mean, what an extraordinary privilege to be able to journey through this life and absorb from people you meet that which you can never discover by yourself. It is simply gorgeous.

And finally, I am sure you being on the teaching side, you must be giving messages to your students, so what would be your message for younger students or geophysicists who are entering our profession in the industry?

For young geophysical students? Find a University where the people who will be teaching you love to teach, and if it is UBC that’s great and if it is Saskatchewan, that’s great, it doesn’t matter which campus, the temperature does not really matter either, the important thing is that those people who teach you, know it, love it, are passionate about it and don’t punish you with it. Read the books of the Greats. Read Broullion, read Weiner of course, read Bracewell, I mean people who really have put a lot of time and effort into trying to teach through their books. Read very widely. Maybe you won’t have time in the first few years, but at least in graduate work read very widely. Read optics because they do stuff that’s beautiful and different in spherical coordinates, so think about these ideas and imagine them in rectangular coordinates. Read the works of those who explain, and explain wonderfully and uniquely, like Robinson and Treitel, Claerbout, Strang and so on. And I repeat for the seventh time, read widely. Those things that I am now so interested in, like the phase of images, come from reading Oppenheim et. al in IEEE and articles about the importance of phase in manipulating type.

Geophysics is a beautiful branch of the tree of science. It is only a branch, however, of this gorgeously complex and fascinating tree. So climb around the branches a bit, you know. Don’t make geophysics like the tree trunk and forget that there are other disciplines that can teach us so much.

Approach all that you do with passion, like my great Slavic friend Genia Landa, humour, as exemplified by Arthur Weglein and humility, Tury Taner will agree but never explain, he is too humble. Never allow yourself to coast for too long, because it might become a habit.

Please remember that “political correctness” is tantamount to lying, at least to yourself. Finally, do not worry too much about what others think, they probably don’t.

Well, do you think I have covered everything more or less, or did you expect me to ask something and I didn’t do that?

Absolutely not. I think you are too wonderful and professional to have missed anything.

I thank you for giving this opportunity and time to sit down and chat with me.

Satinder, when you thank me for what I consider to be both an honour and a privilege, of talking with you, I know not what to say. Well, I will tell you what happens via a story. I was staying with Tury Taner just a few days ago in Houston. I love spending time with him and talking with him and listening to his marvelous collection of music. He is an enlightened soul. I woke up in the middle of the night and the door to my room is open. I think, Christ, I have gone to sleep in the hotel room with the door open. Crazy. Totally jet lagged, hotel lagged and temperature lagged you know.

Why I am telling you this story? Oh yes, I think I am in a hotel, one of the dozens I have stayed in, and slowly reality sets in. And I feel that I am going to wake up and you will not have invited me. I will not have been invited by Satinder for an interview. I will be sitting in my office at UBC thinking, “What the hell do I do now?”

Share This Interview