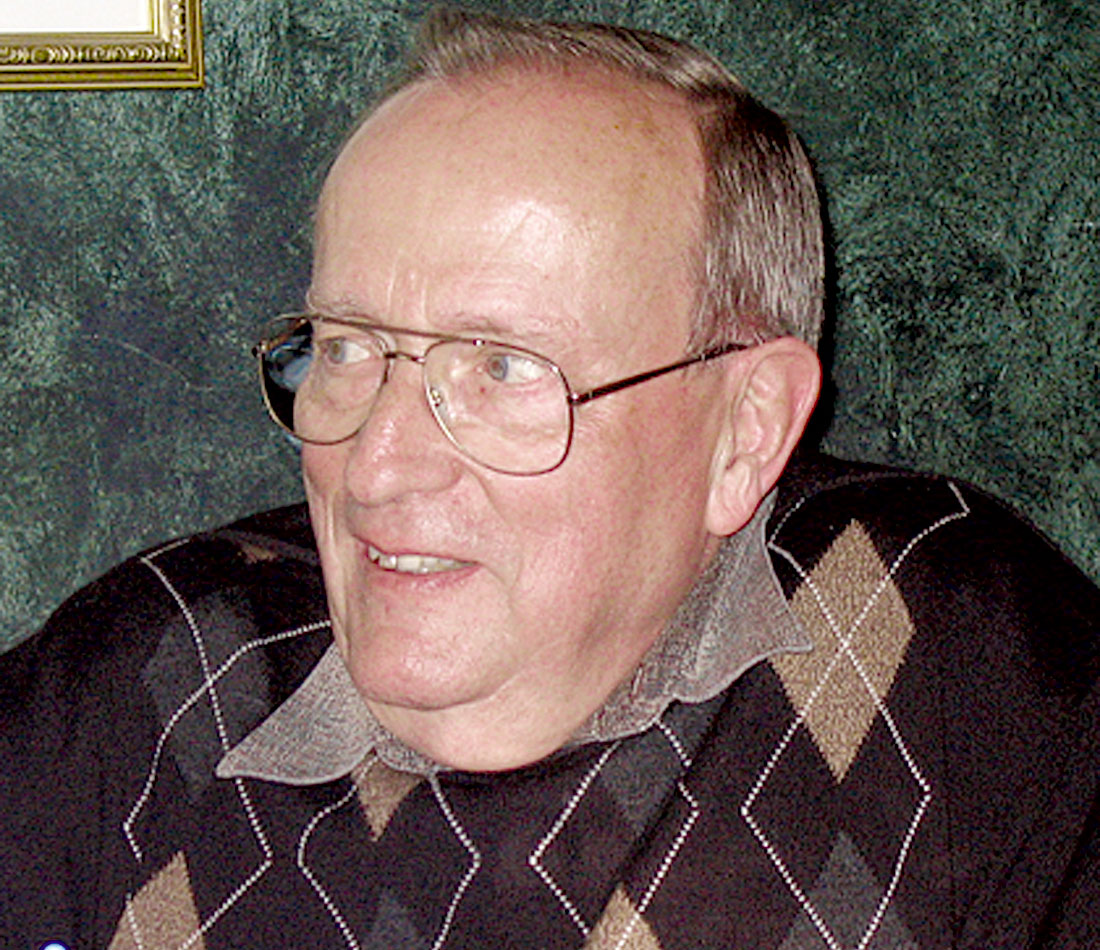

The name Peter Savage brings memories of a well respected and experienced geophysicist to some of us and others would remember him as the former President of the CSEG. Active as a geophysicist for well over three decades, Peter had an exciting time finding his way through different companies and enjoying the science that he practiced, – a time that also gave him the usual highs and lows. Peter was gracious enough to grant us our request to sit down and share his experiences and memories of his life as a geophysicist.

Oliver Kuhn and Satinder Chopra sat down with Peter for a very interesting and pleasant discussion. Following are the excerpts.

[Satinder]: Peter, let us begin by asking you about your educational qualifications and your work experience.

I graduated from McGill in 1948 with a B.Sc. in Math, Physics and Geology, probably the first “geophysics” degree McGill had ever produced. I started in Maths and Physics then took all the undergrad courses in Geology, compressed into a couple years. Shell hired me in ’48 to work for Heiland Exploration who had a seismic contract with Shell in New Brunswick. I worked as a computer – they were people in those days. To start they insisted that I get some field experience, so I hustled jugs, surveyed and loaded holes for about two months. I then came into the office with two months worth of records to work on. It was a great place to start in this business – all steep dip, individual trace correcting and point plotting, then migrating into final depth sections. It made Western Canada look pretty easy when I finally came out in ’49. That changed!

[Oliver]: Peter, when Peter Bediz mentioned that you were a Francophone – hearing that you went to McGill, would bilingual perhaps be more accurate?

I was bilingual as a child, but we moved into Montreal when I was 12. I still retain, perhaps, a 12 year-old’s vocabulary, not a heck of a lot more. We would bandy back and forth in French, Peter and I, and a few others from the Middle East that grew up in French. I still have some - enough to get into trouble but not enough to get out of it.

[Satinder]: So at the time, how did you decide to go into geophysics?

Nobody wanted to hire a geologist! I walked the streets of Montreal, banging on the doors of every mining company to no avail. They didn’t want geologists and weren’t interested in geophysics. There were a few enlightened companies in Toronto that were using geophysics. Hans Lundberg was influential in that field.

[Oliver]: When you graduated in 1948 that would be really the after effect of World War II. What were the economic conditions then? Was there a lot of growth?

There was a lot of manufacturing activity caused by conversion of war-time plants to domestic. In the mining industry it was pretty quiet and quite a few of my class went on to get Masters and Ph.D.s. The oil industry was picking up and well over half the class, eventually, ended up in Calgary. I took 1-1/2 years in New Brunswick first. Shell then hired me away from Heiland and sent me to Calgary.

[Oliver]: How do you feel about ending up in oil rather than mining?

Originally I had high hopes of being a geologist. I very nearly went to Nigeria as a field geologist for a tin company, but fortunately, I think, Bob Brown of Shell called me, before the Nigerian company answered, and offered me a job in New Brunswick and I took it. Life would have changed considerably.

[Satinder]: Is there anything special about your early childhood that may have shaped your perseverance to carry on such a long career?

I was the first in my family not to be a school teacher. My father, however, was always interested in mapping and taught me map reading. I “grew up” in a canoe and wandering around exploring. The exploration business was a natural extension.

[Oliver]: Where did you go in your summers?

Various lakes north of Montreal. Until I was 12 I lived in Grand’ Mere, a little town up in the St. Maurice River country, the new National Park is now close by. The many lakes and great streams for fishing were always a highlight. When we moved to Montreal we continued to spend summers that way.

[Oliver]: So in 1950 you made it out to Calgary?

Well, actually it was the late fall of 1949 when we moved out here.

[Oliver]: What were your first impressions of Calgary back then?

It was a very dreary place, all the houses seemed to be the same, white stucco with grey rooftops, much like the various suburbs of Calgary today – except the whole city seemed like that. There were two places to eat where you could be sure you weren’t going to get poisoned: the Palliser and a tea room where the waitresses were not allowed to wear lipstick.

Looking for accommodation in 1949 was tough. The oilies, as we were called, were to be taken for as much as possible. We even looked at a place with a dirt floor. We finally found an apartment and went on from there. Shell told us not to buy a house as we probably would not be here long. The family are all Calgarians now.

[Oliver]: What were the companies active in Western Canadian Basin then?

Superior, Amerada, Imperial, of course, Gulf, Texaco. Shell was actively returning since their pull out just before Leduc. To rectify that error they concentrated on big targets. Ironically the early staff had recommended a location that would have discovered Redwater, but it was rejected as being too big – a regional feature – by The Hague office. We early on picked up the reef trend south of Leduc with mile jump correlation seismic, but the play was rejected as being too small. Nobody knew how thick the pay would be. Tunnel vision has been with us for a long time.

[Oliver]: Generally speaking it was the major oil companies that we know today then?

No, there were many active small companies as well. Tom Brooks comes to mind, as do Bailey-Selburn and Pacific. There were many fly-by-nights as well, and an interesting stock market. My first set of golf clubs came from trading in Canadian Fortune. I invested $25.00!

[Oliver]: What did your geophysical work involve?

We did a lot of regional work. Mile jump correlation and then continuous profiling over points of interest. The isopach was the prime reef exploration tool. A number of “bob-tail” crews were used, with short spreads and altimeter elevations. On all the crews the preliminary interpretation was done by the Party Chief, in the field. That made for immediate coverage of anomalies. This continued into the era of magnetic tape recording, until analog processing got sophisticated. There was a pre-tape machine for making sections, the Reynolds Plotter as I recall. It used a form of variable area photographic records. Unfortunately for them tape recording came on the scene. They had a life of a couple years or so. For a contractor with many clients it was interesting to see the companies guarding their “secret” presentation methods, some of which had been in use by others for 10 years or more.

[Oliver]: When did land sales become a regular thing, and how did that change the business?

When regular land sales started life was as hectic as it still is today. I don’t know when that was, but I do remember the panic surrounding the sales after Stettler had been discovered. The Shell geophysicist working that area would rush out to the field with his maps and start to work on the records, as soon as they came off the clothes line, where they were drying. I do recall one crisis when the geophysicist put his maps in the wrong car. When he was ready to go, the car, and the maps, were gone. The bids were doubled before we discovered that the “wrong car” had been Shell’s and the engineer, when he got to the well site, found the maps and called in. There was a period with a sale every week. The industry nearly had a nervous breakdown.

[Oliver]: After you left Shell did you go to Nance?

I left Shell to go with Discovery Geophysical. I was part owner, Vice-President, Party Chief and just about everything else.

[Oliver]: How long with Discovery?

It lasted 2 years and 9 months. We went into business on the 19th of September, 1952. I remember the date because that was the day my first son was born. It was a month or so before the end of the exploration boom that was going on. I experienced my first big downturn in our industry that fall, 1952, when Eastern Canada decided it was a penny a gallon cheaper to buy oil from Venezuela than from Western Canada. Our first contract was at Fort Simpson. The boom wasn’t over yet and nobody else wanted the job so we got it on a cost plus basis. It turned out to be a tough prospect with 1500 feet of unconsolidated sand on the surface, and no matter what we tried we couldn’t get any results. The job ended after a month and so did the boom. We survived shooting velocity surveys. It was lucrative but hair-raising sometimes. We were ready to shoot a well in Saskatchewan once when the derrick fell over. They were jarring on a fish, and the A-frame buckled. Fortunately, we were in town having dinner.

[Oliver]: What prompted the departure from Shell?

It was partly because I felt that there was no place for a Canadian in that organization. An old boss of mine from New Brunswick was being shafted, which soured the climate. It lead to a lawsuit that was settled out of court, much to our collective relief, as we’d all been subpoenaed to testify. It did, though, set the precedent for settling wrongful dismissal, which still stands. I enjoyed the work at Shell, and the District level people, but with the atmosphere souring and the opportunity to join a couple others to form a seismic company, and get rich, like all the others, making the break seemed like a good idea.

I then discovered the harsh reality of seismic contracting. We spent two winters working in the foothills southwest of Grand Prairie. To handle the topography we, (Heiland and National did as well), equipped our crew with the newly invented North King all terrain vehicles. For a number of mechanical reasons they failed and this eventually led to our bankruptcy. We had a contract that covered this eventuality but the client decided to break it. As a new contractor we felt that suing our first major client was not too smart. As it turned out, we misread the industry, and it wouldn’t have made a damn bit of difference.

[Satinder]: What comes to mind when you hear the word geophysicist?

To be full of curiosity. The curiosity to figure out what the geologists are guessing at - as to what is down there. They can do their regional maps and all the rest of it, but don’t forget, a couple hundred feet, at the most, from the bore hole they don’t really know what’s going on. I have a fair amount of geology in my background so I could talk to them and work, with mutual curiosity, on the variety of interpretation possibilities.

[Satinder]: What was the most memorable moment of your professional life?

Oh, good heavens, there were quite a few...

[Satinder]: Give us a few then.

I think there was a sequence of experiences. Right off the bat, working in New Brunswick we had very complicated geology, including overturned folds in one prospect. In several areas we shot cross spreads and did a 3D interpretation.

Seeing the structures in the foothills SW of Grand Prairie, quite different from what I’d seen at Jumping Pound. On one line I stuck my neck out and interpreted a 5000 ft reverse fault. As luck would have it, it was confirmed by field geology later on.

Working with Van Mele at Shell was fun, a learning and an interesting experience. I’ll never forget his using the dB ratio to work out compound interest. Shell’s concern with velocity and line orientation, ignored by many of their competitors, led to many of their successes and taught me a great deal.

Going into business for myself, with these others, was a highlight in a way. Going bankrupt was an experience that should happen to more people.

[laughter and chatter]

[Satinder]: What was your lowest point in your career?

It is strange, I was always confident, or ignorant, and never really experienced substantial lows. I suppose the lowest point was when Teledyne took over Canadian Magnetic, and our field crews. They really didn’t understand the Canadian scene and relations gradually turned unpleasant. At that point I left and joined PanCanadian. Going bankrupt with Discovery was a low point as well, however at the time I felt it was the luck of the draw, cost me a little money, but was a great experience.

Having a job to go to with John Fuller at Nance Exploration helped quite a bit. John had been a geophysicist with Standard Oil and was a very adventuresome soul. I think, at this point, we’ve moved from low to more memorable points again. In the late 50’s John Fuller could see things coming, and arranged for us to buy a playback machine from the Carter Oil Co., which was part of the Standard group. We did a lot of processing for Imperial on that machine. The system employed pulse width modulated recording. The field units were the most rugged in use at the time. You could almost destroy the tapes and still recover the signal; the rest of the industry went to less effective equipment. We adapted the Carter machine in two ways. First, we lied to it about spread lengths to change velocity for NMO, and second, because the sections were printed in a lightproof box, we used variable density bulbs which were available in the Radio Shack equivalent of the time and in short order were producing variable density sections.

The processing business seemed to be expanding so we started a processing company called Canadian Magnetic Reduction – or CMR, an easier name for clients to remember. We were the first to buy SIE playback equipment. Both AM and FM crews were appearing at this time. There was a multitude of formats, all close to the hearts of various company research departments. Eventually, with a piece of equipment, the Omitape, and some jiggery pokey, we could process Carter, SIE AM and FM, United, Techno and Magne-Disc. At one time CMR was the largest and most versatile playback centre in the world. At that time 100% of Canadian crews recorded their data on tape, while only 50% of US crews were.

We had many visitors from the US and world-wide to see what we were doing. We had built our own section cameras, and were able to do quite a variety of presentations. We were particularly proud of the variable area device where we could vary the amount of the area under the wiggle trace.

In 1961, after looking at the scattered facilities available in the US we set up a centre in New York, aimed, mostly, at foreign operations. The next year we set up Pacific Magnetic Reductions in Australia. Our best customer in New York was Aramco. They were reprocessing all their data and, with their storage facility a half hour from our centre, it was a natural fit. By the time they had to repatriate their data to Saudi Arabia we had concluded that Houston was a better place for a centre, there wasn’t much organized competition, and so we moved there. Shortly thereafter Teledyne bought us out.

[Oliver]: I have noticed with people in general that their memories and impressions from their earlier years are much more vivid than their later years, even if they have achieved quite significant things later in their lives. You haven’t really mentioned much about the PanCanadian years, but you were there for quite –

I was there for 21 years –

[Oliver]: I would imagine in the geophysical area a lot was happening in that period?

It was. I went there as Chief Geophysicist and later as Exploration Manager, and found that CPOG had a really sad geophysical history.

[Oliver]: CPOG ?

Yes, Canadian Pacific Oil and Gas. They became Central Del Rio just before I joined them – the result of a reverse takeover. They were kind of a strange company. I remember talking to them about the scale of Foothills seismic sections. I suggested a particular horizontal scale that would make the interpretation easier. When they decided on half that scale they explained that that was the only way the sections would fit their storage drawers. It was kind of sad. They were a funny company - quite backward, and always afraid of what the majors would think of them.

When I joined they had just drilled a dry foothills test. To their credit they had shot dip lines two miles apart, but drilled the well half way between. When they asked me what I would do, I suggested another line through the well so we could see by how much we had missed the front of the Mississippian thrust. At this point they demurred, saying, if we did that, the industry would laugh at us. I was not popular when I replied that the industry already was. The Company did change though. With the likes of Lou Stevens, Lou Haakmeister, Lorne Kelsch, Gord Hawkins - a land man - and some good geologists and engineers as well, attitudes were changed, and well before EnCana came along it was a company to be proud of.

[Satinder]: Tell us more about your years at PanCanadian.

The time at PanCanadian was very interesting. I was in geophysics for a couple years, then became Exploration Manager for the U.S.A. – now that was fascinating. It was during the NEP problems. I was in Ottawa for a meeting and a session with Simon Reisman was set up so I could describe the damage the NEP was doing. He was Deputy Minister of Finance at the time, the top bureaucrat in the Department. It was an interesting conversation, more like a fencing match, he with a rapier and me with a pen knife. I had been given a document to give him, but, since it was quite poorly written I really didn’t want to. After telling me I had only five minutes of his time, it took him twenty to get the thing and a lot of good argument from me. The Deputy Minister of Energy Mines and Resources had set the meeting up.

Of even more importance, however, was a meeting he set up with an “expert” in Finance, the source of the information that supported the NEP. When I told him about the crews and rigs moving South he said, “ Well as far as we are concerned that can’t be happening since the United States is fully explored.” At this point I got my business card out and said, “I’m the Exploration Manager for the USA for the biggest Canadian oil company, so let me tell you about the United States.” I started in Alaska and went down the coast to California, up to Utah and Wyoming – we were operating in just about every oil basin in the US at that time and I could tell him about it. We had 800,000 acres of oil leases in Utah, were operating on and off- shore Louisiana and Texas. We were the only Canadian participant in the first joint seismic survey off the US East coast. The processing of that East coast data was interesting with Shell and Mobil trying to keep “their” true amplitude process secret by vetoing true amplitude sections, much to the amusement of the rest of the group.

[Satinder]: What differences do you perceive between those days and now?

A lot of your work is highly concentrated now – we did a lot of regional lines, with a fair amount of, what we thought of then as, detailing. We did start using helicopters and other types of portable seismic crews.

[Oliver]: Well they are extremely efficient. One thing I think would have been very different in your time, and that is if you wanted to start shooting seismic, it would be straight forward. You negotiated with the land owners.

If it was crown land, it required approval, which was pretty well automatic. As I recall, towards the end of my involvement in the field, we had to do a fair amount of clean-up, and pay stumpage to the forestry companies. If you were reasonable the land owners were generally reasonable. I do recall one occasion when the client sent out some newly minted, fresh from an eastern law school, “land men” to permit a velocity survey. It took us a week to calm the land owner down and finally get permission. They kept the hot shots in the office after that. Remember, I got into exploration management in the late 70s, the 3D work was yet to come. I promoted it, but was no longer involved in the nitty gritty.

In the early days I’m sure we cut some lines wider than they should have been. None as bad as the access road to a well in Sylvester Creek that we were towed into, to shoot a velocity survey. It took three days behind a D-7 cat. You know, you can fall asleep on the back of a D-7, I have. It was spring and we were enjoying two weeks of heavy rain. For every second trip into the site they had to create a new road to keep from being completely bogged down. By the time we came out, the road was 50 or so yards wide.

[Oliver]: Have you heard, there is a new product now that rolls up, somewhat like a corduroy mat? They can roll it out on muskeg and extend their operations.

That would be great. In the spring it was always nip and tuck. You wanted to stay in as long as you could, get as much coverage as you could and earn as much as you could. If the client didn’t want to pay if you got stuck, then the party chief would spend many sleepless nights checking the temperature. The first night it didn’t freeze was the sign for the crew to move.

[Satinder]: It is felt that the geophysicists usually like to further their science only, and as a result don’t go very high up the ladder to management positions. What is your opinion of that?

This used to vary from company to company. I, once, came across a Chief Geophysicist who removed all the well locations from the seismic maps, to prevent the interpreters from “cheating” by using the geology! In most places they were a team, but it is a danger now that the science has become so complex. Geophysicists can get so tied up in the science that they do not see, and can not appreciate the whole exploration picture, at least that is the impression they easily give. Processors, in particular, would have trouble moving on, if they wanted to. Geologists, because they have to speculate more, along with a land man to make deals, and engineers, because they’re useful to get holes dug and completed, generally involve themselves in start-ups; while, when needed they will call on consulting geophysicists to find their locations for them.

In the past in many major companies, a geologist and a few geophysicists made it to senior positions. Standard of New Jersey even had a geophysicist on their Board many years ago. Now-a-days fewer and fewer explorers get to the top of these companies. Lawyers, accountants, and, risk proof, engineers who trust only those who speak their language, now make up the major boards. It is a shame to watch them disintegrate.

[Oliver]: They are managing capital.

That’s right – they are not even oil company managers, which is unfortunate. We’ve seen some tragedies where some outside money has bought into a well managed local company. They then feel they need some outside hot shot to make it a real winner. Then, not knowing why, watch it go down the drain.

[Oliver]: Well, I would think that in the past the oil industry was probably guilty of some poor business or management practices, but now it has swung too far the other way. Obviously the oil industry has to keep finding new reserves, but they are so scared of exploration now that I feel unless they rediscover the exploration side, they are going to die out, the big companies.

Yes, the big companies will die out - in a sense. They are now pretty well trusts, the sort of last death throws of an active organization.

[Oliver]: On a more global scale I read a – well it was in the Economist a few months ago – they focused on the oil industry and they said one of the biggest changes of the last 20 years has been that the control of the industry has shifted from the major oil companies to the national oil companies. Companies like Saudi Aramco, the Venezuelan and Iranian state companies are now the top oil producers, and won’t let the majors come in and run the show. They are more sophisticated now and know where they can buy the technology they need, as well as having people trained in the west. The only thing the majors have now is access to huge amounts of capital.

That’s true, though you’d think the national companies could keep some of the funds they generate. Also the industry is still quite successful in some of the more susceptible countries. As regards training, I don’t think the technological expertise has transferred to the national oil companies quite as well as they think it has. Unfortunately, by shutting down their labs, most of the majors are losing that technology as well, even though, in the early days, some of those labs did produce some rather peculiar results.

[Oliver]: Any kind of research effort that becomes too insulated —

Well, that’s right and the majors were all very insulated. When I was a contractor, and I was for 19 years, I encountered just about every major in the business. I learned just how good they were and also just how bloody awful they were as well. Most of their operations were excellent but some were pathetic, and they didn’t know it. Some “geophysicists” chose to retire when common depth point shooting came in – they couldn’t figure out a stacking diagram. Peter Bediz had quite a time with one major getting them to use CDP and then I made myself popular by asking them to let us work it out if they couldn’t. They kept the data for a couple weeks and gave it to us, saying they didn’t have the time to lay it out. Many geophysicists at that time did not understand that one could saturate a tape with noise and leave no trace of the signal. Recording “all the data” with wide open filters ruined many a project.

[Oliver]: When Enders Robinson was up here – or maybe it was Sven Treitel, he mentioned going to a research facility of one of the major oil companies where they were spending days looking at analog filter characteristics and refused to consider the concept of digital.

Having an analog background was very useful for digital processing since you could visualize what you were doing, but you have to be able to accept the digital first.

[Oliver]: I guess it was a leap of faith?

To some extent it was. It is rather interesting, for instance, to have someone on an analog machine add up a suite of sine waves and ultimately produce a spike. That is something they wouldn’t believe if you told them, but having physically put them together helps make that leap of faith. People that started fresh with digital I kind of feel sorry for, but I guess it works out.

[Oliver]: Most of us in our physics classes would have done some analog stuff. I think all of us had that kind of intuitive feeling.

[Satinder]: Let me ask you a philosophical question. If you don’t like to answer it now I will leave it and ask later. You have had a great professional career and a satisfying life. So what are the essences of life, what are your words of wisdom?

Oh my.

[Satinder]: I will leave it with you. Maybe you can think about it.

I never doubted whatever it was that I was doing, however when there was something I didn’t know the answer to, I would admit it up front. This is beyond our company’s capability, beyond my capability, whatever. I think I startled the hell out of a few people when I was a contractor by saying, “ We can’t do that, we don’t have the capability,” instead of bluffing. There was a great deal of bluffing going on in the industry, there probably still is. Back in 1964 (I think it was) a group of us from Calgary attended the first session of the Colorado School of Mines’ course on the math of seismic processing. John Hollister, with two of his staff taught the course. One of the sessions was devoted to analyzing the advertising of a prominent contractor, to sort the truth out from what they appeared to be saying. Coming from CSM that was quite fascinating.

[Oliver]: That’s interesting, I remember someone told me that on the back page of the RECORDER, or maybe the Leading Edge, GSI would always have an ad, and sometimes it was half baked. It was their Company policy to always come out with new ads regardless.

Those were some of the principal ones we analyzed in that course. They were always interesting, and a constant source of anguish to people who would like to be honest and admit, “ Sure, we’re working on it but it’s not developed yet.”

[Oliver]: I read a really interesting book on the history of Schlumberger, and a great deal of focus on their use of the patent process. They would patent technology for several different reasons. They would patent bogus technology to distract competitors, and they’d patent technology just to delay competitors, even though they knew they wouldn’t be granted the patents, it would just buy them some time, so they had no intent of ever trying to enforce it. Of course they did have many legitimate patents where they really did have the technology, but they’d just crank out hundreds of patents and kept their competitors constantly on the defensive.

[Satinder]: Peter, now that you are retired and have all the time you need, what is your typical day like?

Well, this morning I started at the gym, I do Monday, Wednesday and Friday mornings. Yesterday I was playing music with a small jazz group. I’m involved with the Petroleum History Society and the Rock Garden Society.

[Oliver]: I saw your garden.

That’s right. I am also involved in the reconstruction of the Reader Rock Garden.

[Oliver]: Is that the one on McLeod Trail? It’s on the East side –

It’s on the East side just South of the Stampede grounds. It used to rival the Butchart Gardens near Victoria. People touring Canada would stop here in Calgary to look at the Reader Rock Garden, en route to Victoria.

[Oliver]: Reader was the first –

Reader was the first long term superintendent of parks. There had been two people hired, and fired, in the year before him. There has to be a story there – right? Reader was Superintendent for many years and is principally responsible for Calgary being as green as it is.

[Oliver]: Satinder, regarding your retirement question, I was thinking that people develop skills suitable for whatever their life requires and Peter is probably the first guy that turned us into a lunch, instead of the most convenient office. [laughter]

I thought lunches are always a lot more relaxing. Having an office just across from here made this my favourite spot for many years. We had many joint operations and solved a lot of problems right here in The Palliser. For variety or for those who thought the Petroleum Club was “the place” I would use it.

[Oliver]: We haven’t talked about your family or personal life at all. In the early days were they traveling around with you? You have kids don’t you?

Oh yes, I have three, two sons and a daughter. When I first arrived in Calgary, Shell said, “Now don’t go out and buy a house because you are not going to be here very long.” Well, we have never left. That was 1949, so 56 years ago.

[Oliver]: Is that the same house where I saw the rock garden?

Yes, we got that house 46 years ago. And yes, I did a lot of traveling, the longest trip was three months in Australia, three weeks in Italy and all over North America. With “hot shot” seismic jobs, velocity surveys, and being Party Chief in the bush in the winter, you didn’t take your family with you. It was hard on my wife, but everybody was doing it at the time. The sort of thing like coming home Christmas eve and leaving on Boxing Day.

[Oliver]: So, are your kids all school teachers?

No. [laughing] Interestingly enough I managed to break that tradition. One son is a lawyer, the other an engineering technologist with Stantech, and my daughter was both a land man and did oil and gas marketing for PennWest the last few years before moving to Jakarta. All three knew that of all the things they could become a geologist or geophysicist was not one of them. I never did figure out why.

[Satinder]: Peter, how long have you been a member of the CSEG and SEG?

I wasn’t a founding member of the CSEG, unfortunately, but I joined very shortly thereafter, in 1952, in time to play in the first Doodlebug Golf Tournament. That was highlighted by Shelly Winters giving out the prizes. We used pictures of that on a poster a couple years ago.

[Oliver]: Tom Portwood’s son bequeathed those to the CSEG, along with other Doodlebug memorabilia.

We used the picture of B.J. Siemens getting the prize from her. There was some great golf at Banff. Before and after the “season” you could play all day for $2.00!

[Satinder]: You were President of CSEG in ’62, tell us about the Society then.

I had been involved with the CSEG prior to that. I was the first Editor.

[Satinder]: The name was not the RECORDER or something like that?

No. James H. Gray, the popular historian, owned the weekly “ Western Oil Examiner”, and gave us space to print transcribed talks and technical articles. That was probably in the late 50s. I started as Secretary/ Treasurer, then Vice- President. It was customary for the Vice- President to run for President in the next term. I thought this gave the VP an unfair advantage, so we skipped a year. Peter Bediz was elected President that year, and I was the next. I was only 35, with a lot of more senior people on the executive. The Society was very active.

Amongst other things, we introduced an Annual Public Lecture at the Jubilee Auditorium. We started with Dr. Currie from U. Sask., an expert on the aurora. His all-sky camera pictures were spectacular, then we had Kuiper from Arizona, the astronomer, also with great pictures. The real highlight was getting Nobel Prize winner Harold Urey, the first to create life in a test tube. Ed Fulmer and I both asked him to talk on the origins of the universe, however he was more interested in his current research, the chemical composition of meteorites. We had something like 1800 in the audience. When Urey walked out on the stage he stopped, looked, and said, “I can’t believe it.” He mesmerized the audience. While a lot of what he said was over our heads, you could have heard a pin drop throughout the talk. When he finished the talk he looked out at the audience and said, “You know, I should have talked about the origins of the universe.” Ed and I couldn’t believe it, the son of a gun! He was an interesting guy. We didn’t know he had been born on a ranch in Montana when we gave him the Calgary white hat, and a beautifully wood carved chuck wagon. He was absolutely transported, we took him back to his youth. We did some interesting school programs as well. Volunteers would go to the schools and present a series of basic lectures on geophysics. Unfortunately we didn’t keep it up.

[Satinder]: And we now have the SEG Distinguished Lecturer traveling around and —

Yes the SEG has done that, but that’s a technically specific lecture. What we did was public lectures, specifically designed to bring the whole public into the scientific sphere. Half the audiences were school children. Their teachers told them, “You have to hear this scientist. You may never hear the likes again.”

[Satinder]: You were chair for the 1969 SEG Convention?

Yes I was.

[Satinder]: So before that, in ’62, when you were the President of the CSEG, the Convention was held in Calgary.

Yes it was. I had to give the welcoming speech.

[Satinder]: Tell us something about your impressions then about the SEG Convention.

It was a good meeting with some first class people there. One we invited was Sir Charles Wright, the last survivor of the ill-fated Scott expedition to the South Pole. I believe he was the one to discover the hummocks of snow that covered the tents. We had a terrible time to get him to talk about the Antarctic. He was 85 and only wanted to talk about his current research – measuring the pulsations of the Earth’s electromagnetic field, simultaneously, from points diagonally opposite on the Earth’s surface. The Southern readings were being done in Australia and the Northern at Suffield. Milton Dobrin and I went to see him at Suffield. He was in his Jeep, out in the field, taking the measurements. It was a Sunday and his main concern was whether or not the bar in the mess was going to be open so they could celebrate a cricket match between Calgary and Suffield.

Premier Earnest Manning was there to welcome the guests to Alberta. I had to introduce him – a traumatic experience for a 35 year old. I did my welcoming address in French, which was fun, and then I did it in English for those French speaking people who couldn’t understand my French. I was worried about insulting people by translating it, however John Hodgkinson suggested this gambit. Norm Klinck did a great, and much appreciated, job on the entertainment committee. In 1969 Hal Godwin put on a great show, including using the whole of The Palliser for a casino, a night club, a beer hall (with Klondike Kate), etc. We took over the bar, the dining room, the lobby and the stairs and served everybody breakfast. Besides being technical successes, the two meetings gave Calgary hospitality quite a reputation. Most registrants are at these meetings alone, and we thought we should have an evening that they could enjoy. The Palliser staff were most professional and really rose to the occasion. The other main venue did not, which was too bad, and another whole long story.

[Satinder]: You have been the President of the Canadian Geoscience Council and with a regular job, how did you find time to volunteer for these jobs?

I can remember one day my boss asking me if I planned to be in the office that week! I had very good secretaries and understanding companies. When I talked to PanCanadian about joining them I explained that this was the sort of thing I did, I would love to work with them if they could put up with me, they said they could and hired me anyway. In fact I was a candidate for President of the SEG that year. I lost out to Jim Kidder, which was irritating at the time, but probably a good thing in the long run. Changing jobs and being SEG President was not a good thing to do in the same year. Both Teledyne and PanCanadian were very supportive. I took full advantage and life was always interesting. I was industry rep. on the NRC Associate Committee on Geodesy and Geophysics when we phased it out to create the Canadian Geophysical Union whose executive I was on for a while. These committees I was on often met in Eastern Canada, where most of my family lived. There was method in my madness.

[Satinder]: Are you optimistic about the future of our industry?

Oh I think so. It is going to change and it has changed quite a bit. As explorers I think the majors will just fade away. The level of activity may drop, but there will always be people with ideas that need geophysics to get at the oil left in this basin. One of these years someone is going to figure out how to get the oil out of the Second White Specs. That has been one of my pet things, one I failed to accomplish. We had a go at Coal Bed Methane, without much luck, but I understand it’s coming into its own now. How geophysics fits in there is a question. The tar sands will take some of the heat off finding oil, at a price. I recall, around 1958, Stan Paulson, who had ruined his wife’s washing machine spinning the oil out of a tar sands sample, saying that, if we could get $3.50 a barrel for oil, the sands would be economic and all the exploration guys would be out of work. Oil was at $2.50 then.

[Satinder]: Well, what would you say are the exciting aspects of a career in science. Could you say something to young entrants in our industry?

It’s constantly changing, even now. It is exciting to use science to try to determine what’s there, and to discover that you are right, or, that you are wrong, and find out why, which can be even more important. I had a little award that I used at PanCanadian for a short time. It was called the “back to the drawing board” award, for those who had drilled a dry hole. It was based on a New Yorker cartoon – with a crashed plane in the background we see a designer, with rolls of plans under his arm, walking away, saying, “Well, back to the drawing board.” You don’t have to be the one drilling holes for the work to be exciting. The data processor has the real challenge to faithfully reproduce what’s happening without creating artificial anomalies or lack of anomalies. It is so easy to make a “beautiful” nice and smooth section that says nothing, but management loves to look at. It can be an exciting business, but you really need to be aware of the whole picture. Parts of it can get cloudy if you are not aware of how your data is being used.

[Satinder]: Are you surprised about any questions or topic you had in mind and we didn’t bring it up here?

That will probably occur to me tonight!

[Satinder]: On behalf of the RECORDER and the CSEG, thank you very much for this very interesting interview.

[Oliver]: And for choosing The Palliser for lunch!

You’re very welcome.

Share This Interview