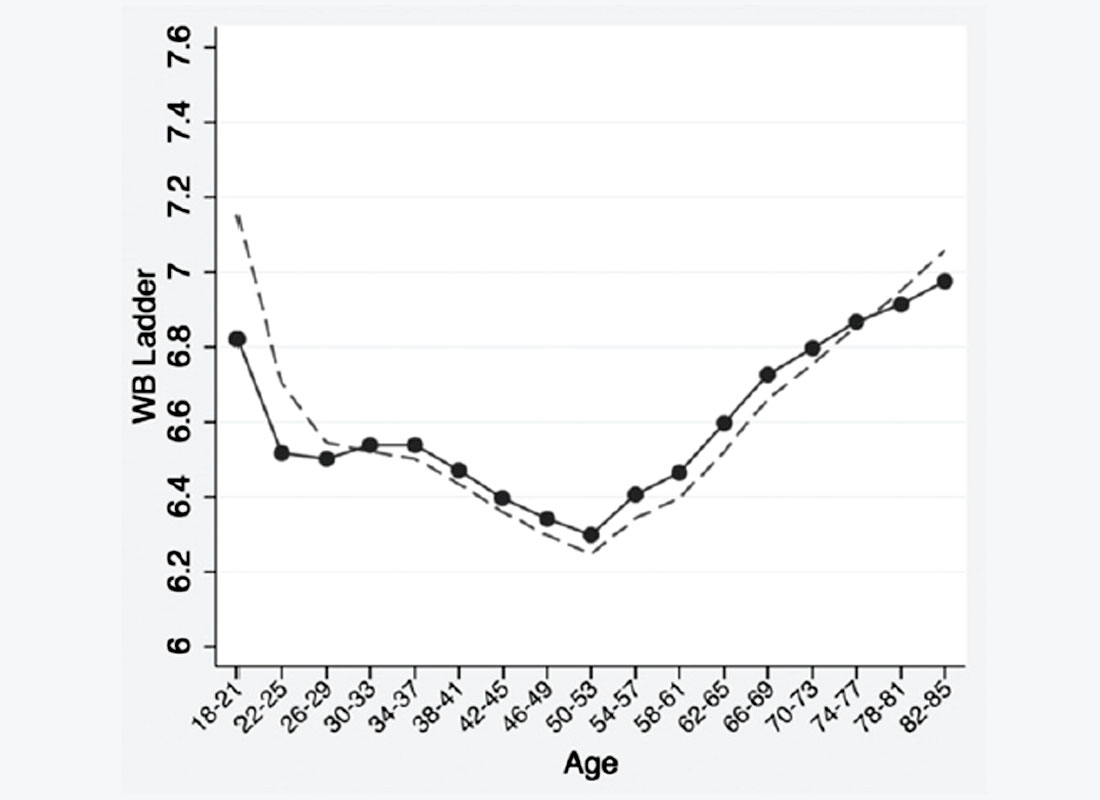

This curve (Figure 1) describes the level of general happiness over an average person’s life. Studies are consistently showing the same result – human happiness starts high in youth, reaches a low point in mid-life, and then rises until death. Our late life happiness levels actually exceed those of youth. This intrigued me when I first read about it in The Atlantic (Rauch, 2014), as I found it counter-intuitive: surely we’re happiest when young, and then as the depredations of age take their progressive toll we become increasingly less happy, right? I picture myself alone and miserable, wearing Depends and playing Bingo in some seedy home my children have banished me to. But as I reflected on my own life and discussed the article with friends, I realized that the U-curve actually does fit my own experiences. This phenomenon is encouraging and so I want to share it – those who are in the trough will be happy to learn that it’s going to get better; those past that and on the rise will be cheered to hear that they’re not imagining it and the trend will continue; finally, those still in the halcyon days of youth will be alarmed at what’s in store for them, but at least will be armed with some pre-knowledge.

Note that these sorts of sociological theories are prone to all the usual statistical pitfalls – sampling inadequacies, biases, confounding factors, issues around self-reporting, etc. – and thus are somewhat fuzzy. There are many experts who disagree with the findings, and don’t believe the U-curve theory fits reality at all. But from my current perspective, I like these theories and they fit the life narrative I’d want to follow, so I’m putting my skepticism aside and accepting them with an unrestrained optimism that only a 55+ male can understand.

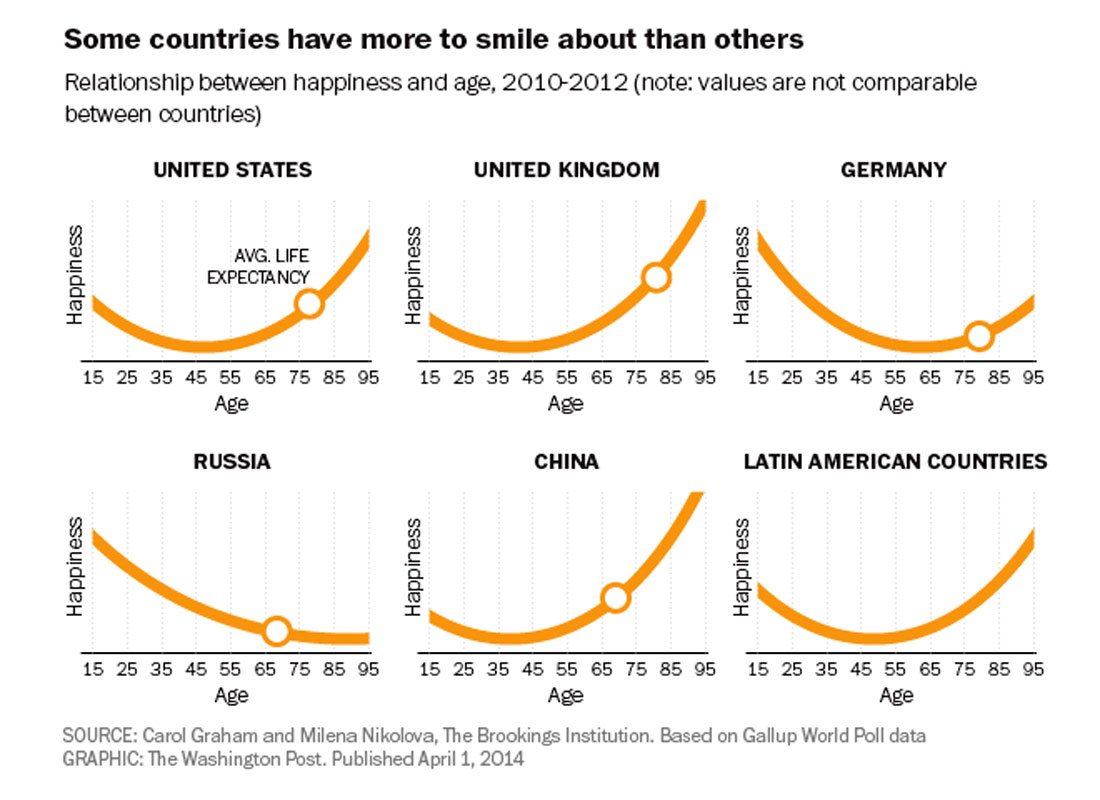

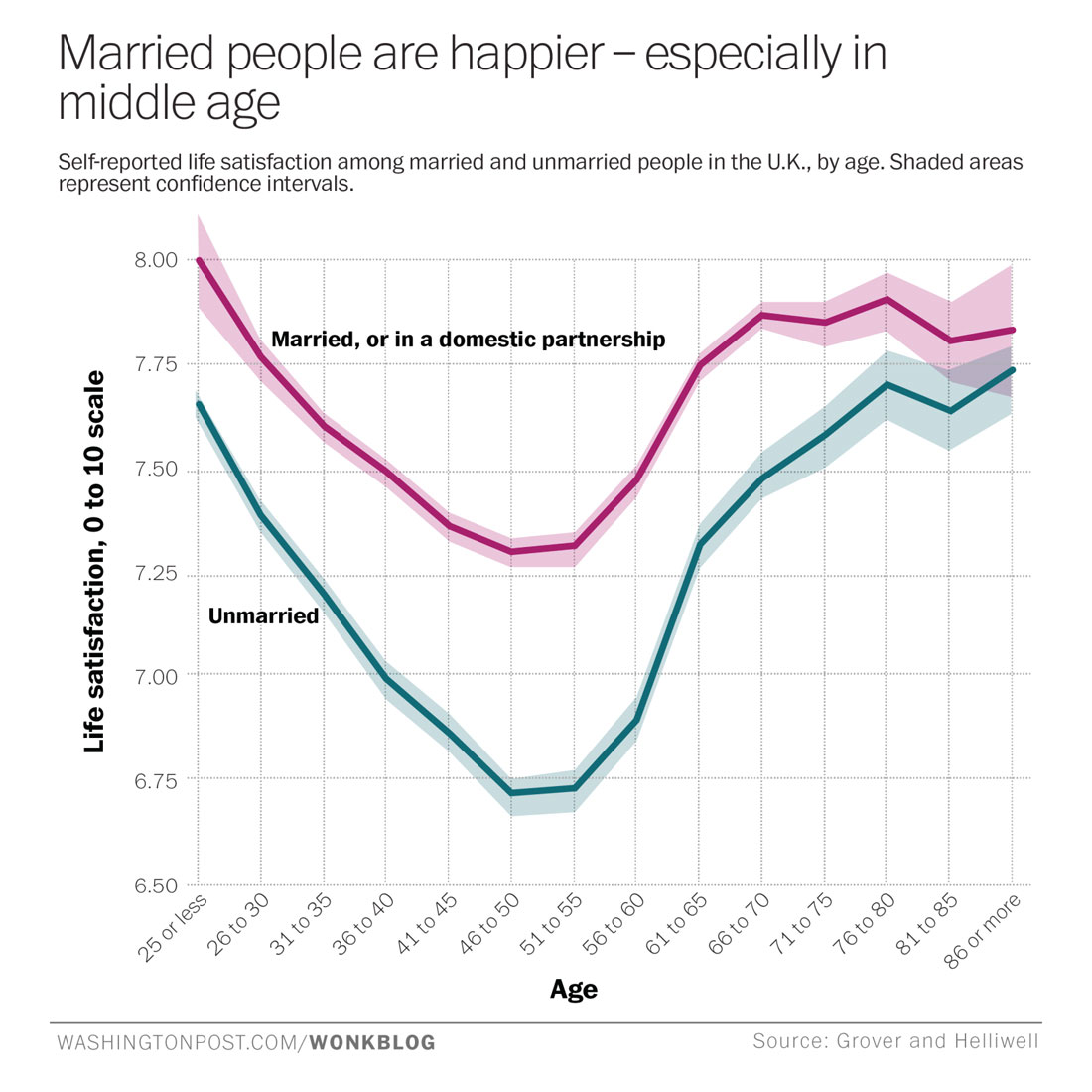

Collecting data on human happiness is currently in vogue, with perhaps the most ambitious example being Bhutan, where Gross National Happiness numbers guide federal policy. Countless researchers globally are conducting surveys measuring happiness, emotional well-being, and other quantitative indicators of general and specific life satisfaction. All these data are being sliced and diced by sociologists, economists and other purveyors of the dark statistical arts. The U-curve connection between age and happiness is not the only trend identified – other equally interesting relationships between happiness and gender, psychological makeup, and other life factors such as children / no children, married / not married, religious / not religious, nationality, race, socio-economic ranking etc. have also emerged (E.g. Figures 2 & 3).

Youthful happiness and mid-life angst are commonly accepted life stages, but a rise in happiness after middle age is a new concept. It makes sense though. Youth should be fun and happy, given all the cavorting around that goes on in those years. Marriage, children and middle age bring on all sorts of factors that can explain increasing unhappiness – mortgages and other financial stressors, increasing job pressure, loss of free time to children, the minefields of marriage, health issues, etc. So it follows that as these factors recede in the rear view mirror – house is paid off, parasites move out, medical issues are dealt with, mistake marriages are terminated, and so on – our happiness levels should rebound. But there appears to be more to it than that. The U-curve persists even when these other variables are accounted for, so what is behind this apparently universal fall and rise that our psyches go through as we age?

One theory holds that the curve is linked to the mismatch between our expectations and real outcomes. When we’re young we feel the world is our oyster. Pop-psychologists feed this youthful mantra back to us, and we lap it up. “Whatever the mind of man can conceive and believe, it can achieve.” “The most difficult thing is the decision to act, the rest is merely tenacity.” “Every strike brings me closer to the next home run.” But as our 20’s go by most of us start to realize that we are not the next Amelia Earhart or Babe Ruth. The disconnects between our dreams and our day-to-day realities relentlessly remind us that life is slipping through our fingers like so many grains of sand, and we are not as special as we once thought. By our mid-40’s these nagging doubts have become a full blown crisis of self, and we respond by resetting our life goals to something more modest. Instead of playing a sport with championship dreams, we now play for exercise and the enjoyment of modest competition; we realize that our children aren’t geniuses or virtuosos, and accept them for who they are. We become more accepting of our spouses and more at ease with our own flaws. And then something magical starts to happen – our achievements begin to exceed our expectations, and the resulting happiness starts a lasting and positive feedback loop. Without going into tedious details, I can tell you I’m experiencing this – I roll better with the setbacks and appreciate the small victories far more, and there is a sense of calm, living in the moment and being at peace with myself that wasn’t there before.

There is evidence that this U-curve effect is an extremely basic aspect of the human condition; in fact one study suggests that it is hardwired into great ape neurochemistry. Weiss et al (2012) studied the mental well-being of over 500 chimpanzees and orangutans (in zoos, research centres, and animal sanctuaries – humans close to the subjects obviously did the reporting, not the primates themselves!), and the exact same U-curve emerged, with age shifts reflecting the apes’ shorter life spans. The notion that I share a similar life outlook with a silverback gorilla in the Congo, or a past-his-prime orangutan deep in the Sumatran jungle is somehow reassuring – all is as it should be. With that I wish everyone a great summer, and will be back in the fall with a fresh set of articles.

Share This Column