I think about Paris when I’m high on red wine,

I wish I could jump on a plane.

And so many nights I just dream of the ocean.

God, I wish I was sailin’ again.

Oh, yesterdays are over my shoulder,

So I can’t look back for too long.

There’s just too much to see waiting in front of me,

and I know that I just can’t go wrong.

With these changes in latitudes, changes in attitudes,

Nothing remains quite the same.

With all of my runnin’ and all of my cunnin’,

If I couldn’t laugh I would sure go insane.

Changes in Latitudes

JIMMY BUFFET

There has been a powerful social trend recently towards more open attitudes concerning mental illness. Mental illness is very prevalent, with about 1 in 3 people experiencing symptoms at least once in their lifetime, meaning many of us have grappled with it, and each of us most certainly is close to several people who have been afflicted. My father suffered from bipolarity, and my younger brother was a sociopath. Surprisingly, my father died of natural causes at age 83 (the dark joke within the family was that he was the world’s worst handyman), but my brother unfortunately passed away at age 44 due to substance abuse related causes associated with his condition. Being close to these situations has given me a perfect vantage point to contemplate mental illness in its many complexities, and being genetically related to ponder its causes.

When I was young I had such a simplistic view – either you were crazy or you weren’t. But then over the years I saw my father cope with his violent swings between mania and depression while building a successful career as a respected university professor and transport economist. My brother had intelligence, talents and charm that people would envy, yet lived a life apparently devoid of meaningful relationships, and lurched from one parasitic fiasco to the next. Can science explain the complex inner workings of our brains, and explain things when they go wrong? This month’s article combines my high level report on the current state of knowledge and research in a number of interesting areas of neurology, with Steve Lynch’s unique personal perspectives. I want to emphasize that this is a deep and broad topic, science does not have it all figured out, and we’re just barely scratching the surface with this article.

Hi, my name is Dr. Steve Lynch. I am 61 years old, and have been married for 30 years. I have two children and one grandchild who is, as of this writing, 3 months old. For reasons soon to be apparent, I have few memories of my own children at her age, so sitting with her is one of the joys of my life.

I am happy and productive, as I have been for almost my entire 36 year career. I cycle, I hike, I play squash and I am continually amazed at the difference between my youthful perceptions of aging and the reality. I am nowhere near as old as I thought I would be at this age!

I am also a great believer in the power of positive thinking (or self-delusion as my children like to call it). I have perhaps as positive an attitude on life as anyone you will ever meet. I believe in myself completely and the future holds no fear for me. I look forward to each day and I never allow myself the indulgence of depression.

And I am all this despite the fact that without medication, I am seriously mentally ill and have been for almost 30 years. I have been diagnosed with, among other things, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which plays havoc with my emotional levels, and intrusive thought obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), which if I am careless, will rob me of 80% – 90% of my thoughts in a day. One of the other things is that I am also manic and cannot, therefore, sleep, rest or relax.

That is now; in the past, for about 15 years, I was manic depressive and, as a separate entity and not an amalgamation of symptoms, from November 1986 until around May 2005, I was clinically insane, but functionally insane – I met the clinical definition of insanity but was still able to function in normal life.

Life, for me, always has been and always will be, very complex.

Unlike physical ailments, mental illnesses manifest in the sufferers’ thoughts, feelings and actions. This lack of direct tangible symptoms means mental illnesses have almost always been viewed differently than other types of illnesses. They are often seen as being the fault of the ill person, or the result of some paranormal force (“The devil got my child!”), or some kind of divine retribution for moral or other deficiencies. This article will focus strictly on the neurobiological aspects of mental illness. Thanks to tremendous advances in medical research, it is increasingly understood that most mental illnesses are directly related to disturbances in brain function, and further, that these disturbances can be explained by scientifically defensible mechanisms.

This is a huge, huge topic, so rather than try to take on too much, I’ll stick to a few neurobiological tidbits on the disorders that Steve has mentioned – PTSD, OCD, and bipolar disorder (or manic depression as it used to be more commonly called). I’ll leave sociopathy for another time, as it is super interesting in several ways, and worthy of an article on its own.

These are startling admissions given the stigma that surrounds society’s general perception of mental illness. It is that perception that I have set out to attack because it is completely wrong. You have it wrong now; I had it wrong for almost 30 years and we will never get it right unless people who are living with it start to open up and talk about it. And that, with the professionals’ and my family’s support, is what I have committed to do.

You may think that this is a dangerous subject to open up about and that it might have career ending implications. Forget all that. If there is one thing I have learnt it is that mental illness is a silent killer. It does its damage in silence and in seclusion. I am free to talk about it now because I lived in that enforced, very private, vacuum for decades and believe me, there is nothing left that it can do to me that it has not already done.

So I am going to talk about it as openly and as directly as I can because any consequences that come from it are minor compared to the dangers of staying silent. To that end, this is my second time talking about my personal experiences with mental illness. A few months ago, I produced a video for Bell Canada’s “Let’s Talk” program. In it, I discuss what mental illness is like to live with. I talk about everything, including the thought that suicide can become a logical and inevitable solution. If you are in any way touched by this subject, I recommend you watch it. Here is the link to the video. It says everything that I need to say on the subject of what life is like for me on a daily basis: https://vimeo.com/channels/thepaininthemind

Bipolar disorder occurs in approximately 3% of humans. The dominant symptoms are alternating periods of mania with unusually high levels of energy, confidence, happiness (although sometimes to the point of psychotic behaviour), and periods of depression with exactly the opposite characteristics – low energy, lack of confidence, and feelings of hopelessness. The period of the cycles varies greatly between individuals – my father’s manic phases lasted a year or more, and his depressions a bit longer – but typical periods are three to six months.

There are several popular theories explaining bipolarity, but almost all experts acknowledge there is a strong hereditary factor. There is ~40% concordance of bipolarity in identical twins brought up in totally different environments, compared to ~5% among fraternal twins. So all theories start with a genetic predisposition to bipolarity, then require some traumatic form of stress experienced at an early age to trigger physical changes in brain chemistry. It is the type of brain chemistry change that separates the different theories, but most researchers agree that there must be a combination of neurochemical factors at play.

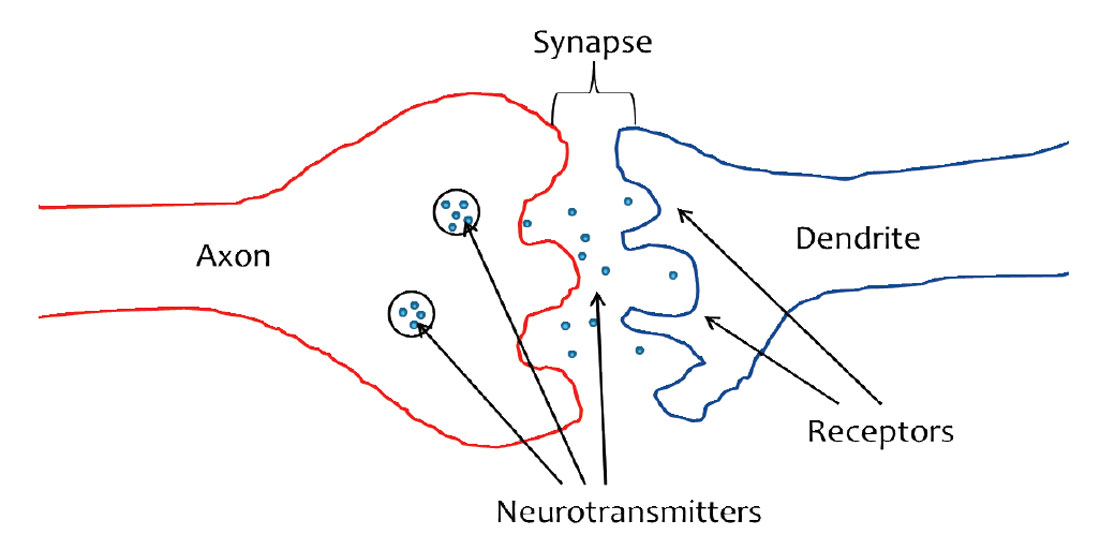

Many popular theories around bipolar disorder involve the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, plus a few others. Neurotransmitters are hormones, little chemical “messengers” that the body uses to send signals from one nerve to another (Figure 1). Neurotransmitters are released into the synaptic gap by the presynaptic nerve’s axon terminal, and are briefly available to bind to dendritic receptors in the postsynaptic nerve. If they successfully “make the leap” then the message is received, and some further action in the receiving nerve is triggered. Note that the release of neurotransmitters from the axon involves the electrical properties of calcium ions, but I won’t go into that here. For those interested, this website has some nice little visualizations of the entire process: http://web.williams.edu/imput/synapse/index.html.

Manic phases are associated with high levels of dopamine, and low levels of serotonin are associated with both mania and depression. It is tempting to jump to the conclusion that abnormal levels of certain of these neurotransmitters cause bipolarity, but it appears to be more complex than that – the high or low levels of this neurotransmitter or that are effects created by underlying issues, not causes of the mental illness. My very simplistic understanding of the whole business is this. (1) Our senses pick up information. (2) Our brain interprets the information and “decides” on an appropriate reaction. (3) Messages are sent to various glands to release the appropriate neurotransmitters. (4) The appropriate levels of neurotransmitters diffuse through the body, instructing the various parts to do their thing.

I read a very compelling Scientific American article several years ago which I unfortunately can’t seem to find now. My recollection of what it said is that in many cases of bipolarity, it appears that the brain has a messed up “fight or flight” response at a neurochemical level, and the damage is probably related to traumatic stress. In my father’s case we suspect it was his traumatic experiences in WWII (he was a Luftwaffe radio operator). The “fight or flight” response is triggered by serious threats, and has obviously served the human species well over the millennia. In these cases of bipolar disorder, the threshold for what constitutes a serious threat has somehow been reset too low by the traumatic experience. As a result many experiences that an unaffected person would brush off trigger an oscillating ”fight or flight” response in the bipolar person, with fight being the mania, and flight being the depression. In other words, what we experience as normal ups and downs in a day can appear life threatening to the bipolar. Their brains send inappropriate signals to the adrenal glands, pituitary glands, thyroid, and often in the case of dopamine, the hypothalamus; these various glands secrete neurotransmitters as instructed, and the result is a physical manifestation of a mental disorder.

Often after suicides you will hear comments like, “Poor guy, his heart was broken when she left him, and he just couldn’t face life anymore.” These over-emphasize the cause, and overlook the exaggerated response – guys get ditched by girls all the time, and do just fine. In the case of my father I recall that political backstabbing at his university appeared to trigger one severe depression, but political backstabbing among university professors is commonplace, depression and suicide are not.

There is an interesting theory that bipolar disorder is a behavioral relic of an adaption that benefited primitive humans living in ice age environments, something like a human form of hibernation. The thinking goes that a person wired correctly for such an environment would be capable of intense activities during the long summer days when food was plentiful and days were long, and then slow, low energy periods during winter when the time was mostly spent dozing in frigid caves. It is notable that Africans have much lower rates of bipolarity, and they were never exposed to winter climates in the distant evolutionary past.

Having already talked about what it is like to live with mental illness in the video, I will just talk about what mental illness is from a real world perspective and briefly touch on what causes it. Let me begin by saying that there is no single ailment called mental illness because it takes many forms and has many origins. Before I go on, I want to stress that I am only talking about what I call “late onset” mental illness, in other words an illness that developed later in one’s life through exposure to some form of severe physical, emotional or sexual abuse – people who develop it, not people who are born with it. That is something else entirely.

Let’s start by talking about how it begins and what triggers it. The almost universal trigger is exposure to extraordinary stress. It can be short term exposure such as is experienced by people in the military or it can be long term exposure to extreme situations. Regardless of the duration of the exposure, the key element is how far the trauma or stress lies beyond normal human experience. We all experience trauma in life but it does not necessarily change us. Changes such as take place in the development of mental illness only come about when the trauma lies far beyond our ability to absorb. I am a typical example because I only became mentally ill after a decade long experience with physical trauma that lies well outside the normal range of human experience.

When I began my career in 1977, I was as normal as any of the young men and women around me. I was fit, healthy and ambitious and the idea that I might one day be diagnosed insane was not something I remotely considered. Then, in January 1978, a soccer ball drove my left condoyle completely through the meniscus that separates the jaw from the skull. The meniscus slipped out of the joint leaving the mandible grinding bone on bone against the skull itself. The force of the impact also caused a radiating temporal bone skull fracture and gave me a Level IIIb concussion.

As a result of the injury, over the following year I began to experience three primary symptoms. The first was a series of outbreaks of Recurrent Cerebral Meningitis. Each episode lasted between 7 and 14 days, elevated my temperature to around 104, and over the next 12 years I had about 30 outbreaks. While not as universally fatal as Bacterial Meningitis, each outbreak was still potentially deadly.

The second symptom was a resident migraine caused either by irritation of the Trigeminal nerve or by the physical displacement of the joint. It came and it remained constant for nine years, destroying in that time my ability to focus for more than a few seconds at a time.

The third and by far the most debilitating symptom, was a whole body sensation that felt like every cell in my body was filled with acid. It originated when the condoyle come into direct contact with the innervating nerves of the TMJ. The nerves are from a long forgotten branch of the Trigeminal nerve and they are morphologically identical to dental nerves. When the condoyle came in contact with them, the pressure produced what the surgeon who repaired the joint called, “the sensational equivalent of having three dental nerves drilled into simultaneously.”

I will leave for another day any discussion of what this all felt like and why it took nearly nine years to find. It is enough to say that whether I was aware of it or not, that is the level of pain my brain experienced every minute of every day for nine years. The meningitis, the resident migraine and the acid sensation all lay well outside the range of any illness or pain I had experienced before or since.

And the nine year duration produced permanent neurophysiological changes in my brain.

Experts also believe that obsessive compulsive disorder is a condition that is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, i.e. both nature and nurture. OCD has become a bit of a joke in society and the term is thrown about in jest. People who suffer from it don’t find it funny, and are usually aware that their behaviour is viewed as abnormal and inappropriate, and this often increases the feelings of anxiety they experience. They deal with their higher than normal levels of anxiety through behaviors that are considered normal in small amounts, but obsessive when displayed repetitively and uncontrollably – constantly cleaning, picking at one’s skin, hoarding belongings; the range of behaviors and urges is extremely broad.

One popular theory explaining OCD involves serotonin. It is thought that an underlying physical condition, again possibly or probably caused by trauma, involves higher levels of an inhibitor in the synaptic gap, which results in lower levels of serotonin uptake by the receptor nerve. Serotonin is considered to play a key role in the regulation of anxiety. A bit of anxiety is good, but too much (in this case) is not. So perhaps this is another way of looking at Steve’s following point. Often mental illness isn’t really a case of something being broken, it’s a case of a system which modulates a desirable and necessary human behavior not being properly tuned. For example, a moderate level of anxiety about one’s appearance will motivate a person to self-groom. Statistically over thousands of years, better groomed individuals likely experienced higher reproductive rates, and thus the ‘anxiety = grooming’ trait became entrenched as part of the normal human neurological makeup. However, if a person is already genetically predisposed to be at the higher end of the self-appearance anxiety spectrum (the “Do these pants make me look fat?” end), and then experiences some intense trauma at an early age (say sexual abuse), this could somehow upset the calibration enough that either anxiety levels are pushed higher and out of the normal range, and/or the threshold level which triggers self-grooming is lowered below normal. In my crude way this is how I picture the combination of nature and nurture resulting in a mental disorder.

My jaw was reattached in April 1987 and after surgery, the pain and the migraine went away and they have never come back. But it is now 27 years later and I am still dealing with the psychophysical aftereffects, and that brings me to a very important point. Mental illness, which is what I was left with, will not go away on its own. It will not go away through therapy or analysis or “coming to terms” with things. Time does not heal all things and in this case, for very good reason. Time cannot heal it because there is nothing to heal!

The term “mental illness” in a situation like mine is a misnomer because there is no illness involved. There is no disease; there is no injury; and there is absolutely nothing to heal because mental illness is simply a natural neurophysiological adaptation to extreme stress. Your brain adapts to unusual and overwhelming stress, it changes your behavior while the stress exists so you can function. When the stress goes away, the behavior doesn’t, but now we call it an illness. It is nothing of the sort; it is extreme but perfectly natural.

When I began to recover from the surgery in late 1987, both my wife and I knew that I was having severe emotional problems. It was hardly surprising given what I had lived through but I have heard other people with similar experiences say this: “I just expected the problems to melt away.”

I thought I would just go back to the way I was before. Instead, I began experiencing wild, erratic mood swings that would take me from euphoria to depression in seconds, sometimes a dozen times a day. I was subject to wild emotional outbursts, over-heightened emotions and a manic energy that would not let me stop, rest or sleep. I could not focus on any task for more than a few seconds at a time and I could not, even though it nearly cost me my life, engage in rational internal debate (one of the definitions of insanity).

I was, even though nobody realized it, stark raving mad and it would not go away. No matter what I did, no matter how much time passed, it would not go away. If any part of this strikes a chord in you, either because you are experiencing it yourself or because someone close to you is experiencing it, then you need to listen to this very carefully: it will not go away on its own.

Children who are sexually abused are affected by it for the rest of their lives. People who live through long term captivity or prolonged emotional or physical abuse are affected by it for the rest of their lives. I have been affected by it for 30 years and unless I take medication, I will be affected by it for the rest of my life. I’ll say this again; you are affected by it forever, because what we call mental illness is simply a neurophysiological adaptation.

So what actually happens to alter our neurochemical systems during extreme stress? Bruce McEwen (2007) says, “Early life events influence life-long patterns of emotionality and stress responsiveness and alter the rate of brain and body aging. The hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex undergo stress-induced structural remodeling, which alters behavioral and physiological responses.” The way I interpret this is that our brains are designed to partially wire themselves in response to their early, and to some extent later, life environments. It is known that there is no fixed scale for human experience – our brain’s interpretation of what is “normal” somehow shifts so it falls somewhere in between the highs and lows. The way we experience the world around has built in gain controls that shift the experiential intensities. This explains why a male hunter-gatherer will experience the same level of joy at finding a tasty little nut or berry, as a North American millionaire does upon buying a new sports car. Survivors of Nazi death camps relate how the happiness triggered by modest events, such as viewing the first bird of spring through the barbed wire, was never again equaled during the rest of their lives. This means their “happiness meters” were somehow set during those awful holocaust years, and never returned to what we would consider normal.

Subject any human being to extreme prolonged stress, be it physical, emotional or sexual, and eventually their neurophysiology will adapt to the changed circumstances. It has to. To a large part, these neurotransmitters provide the power to the engine that drives us. They are, physically, the agents that motivate us. They get us out of bed in the morning and they keep us going even in the most extreme circumstances.

But if your circumstances become extreme, they have to drive you harder and so your brain adapts. You become more sensitive, your drives become stronger, you function, you go on but there are side effects. That is what mental illness is, it is the common term for the collective side effects of extreme neurophysiological adaptation. Intrusive thoughts, manic depression, mania and overwhelming constant emotions are not an illness, they are the side effects of surviving and knowing that, now we can deal with them.

Genetics plays a much smaller role with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than with bipolarity and OCD, especially with more severe forms of trauma. The victim of the trauma tends to suppress the memory of the event, and associated thoughts and feelings. However, the traumatic event comes back to haunt the person via intrusive thoughts, flashbacks and nightmares, but often the sufferer experiences amnesia about the trauma itself and has no idea what the cause or source of these apparent inner demons are. If the condition persists for longer than 3 months it is considered chronic.

Once again, it is commonly thought that PTSD is likely an overly active evolved trait, in this case a threat reaction system which has been beneficial to humans. If, say, a primitive human entered a cave and narrowly avoided being killed by a bear, then recurring nightmares about bears and caves and darkness would most certainly cause an avoidance of these things, thus making his or her future survival and ability to procreate more likely.

PTSD has been linked to numerous factors such as an inhibitory neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5), and several different neurotransmitter receptors (estrogen, dopamine, serotonin, etc.) Many of these factors have also been linked to specific types of stress, such as childbirth trauma, medical injury, alcohol related trauma, victims of violence (e.g. experiences during the recent Rwandan genocide), and so on. What this suggests to me is that each type of trauma perhaps has a different effect on the neurochemistry of the trauma victim, resulting in different variations of PTSD. In fact, if you take a step back, one might say that in general, if you combine the huge range of genetic variation in the human species and associated predispositions, with the smaller (but still huge) range of possible types of trauma, you get the very large range of mental disorders and their myriad variations and combinations that are experienced by people.

I am a person who slays my own dragons. I have slayed a lot of them since this began but if there is one thing that I will leave you with, it is this: mental illness is a dragon no one slays alone. You can throw yourself at it mind body and soul and you can change the things you can change. But beneath it all is an underlying neurophysiological adaptation and to manage that, you need help.

In my case, help is called Seroquel and it reduces my brain’s sensitivity to serotonin. It is a wonderful drug and taking it has stabilized me. The mood swings are gone, my emotional levels have returned to manageable levels, the manic behaviors have ceased and for the first time in decades, I can sleep. For 30 years, I never slept for more than about 50 minutes at a time and to sleep now is a joy and a relief that few people will ever know.

Life is so much better. After all these years, it is returning to what, for me, passes as normal. But that only started to happen when I finally accepted that the things I was “dealing with” were not being dealt with, had not been dealt with and would never, on my own, be dealt with. I had to accept a medicated normality and to do that I had to understand that none of this was my fault and that my failure to control my mind was not a weakness.

I could write a book on what that thought does to you. It is, perhaps, the most difficult aspect of mental illness to overcome. The thought that you are just weak, that you should be able to control this yourself, drives people into silence, seclusion and ultimately suicide. But there is now no need for it because behind every mystery is a simple truth. In this case, the simple truth is that mental illness is neurophysiological and not psychological.

As a society and as individuals we need to accept that and all move on.

Dr. Steve Lynch is the founder and Principal Investigator for 3rd Science Solutions. He received his B.Sc. in Biophysics (with Distinction) from the University of Guelph in 1975, and his M.Sc. in Geophysics from the University of British Columbia in 1977. Following a 26 year absence from academia, Steve returned in 2003 to study seismic visualization and received his Ph.D. from the University of Calgary in 2008.

Steve has a wide range of experience in both geophysical research and software development. Early in his career he managed seismic processing centers and developed techniques for such varied subjects as refraction statics, depth migration, ray trace structural modeling and stratigraphic modeling. For the past ten years he has focused primarily on aspects related to seismic wavefield visualization.

“Wavefield visualization is the entirely new science and technology of visually reconstructing acoustic seismic wavefields. Seismic is one of the most complex and fascinating data types in all of science. I have always loved it and the prospect that it might contain another quantum level of detail is just too much to ignore.”

Share This Column