My plan for this column has been to steer away from the social sciences and stick to the “purer” ones, despite the fact that I am extremely interested in many of the former, especially anthropology, history, and archaeology. This month I am breaking with that rule, mainly because I read a book that has me so excited that I can’t resist sharing some of its details.

The book is 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus, written by Charles C. Mann. There are two main reasons I’m excited: first, Mann summarizes decades of work in a wide variety of scientific fields that I was completely unaware of, and second, the theories he summarizes have completely turned my thinking regarding historical North and South American Native cultures upside down.

1491 essentially provides a high level summary of a consensus that seems to be forming regarding the nature and scope of pre-European cultures in North and South America. The word consensus may be a little too strong or perhaps premature, because there is still a lot of disagreement between experts in different areas, but there are emerging trends of thought based on work in a diverse range of disciplines, many hard science, that are quite at odds with what we were taught at school and hold in our collective consciousness. This new picture could be boiled down to three main components:

1) Native populations were much, much higher than previously thought, and were drastically reduced by diseases introduced by the Europeans to which the Natives had extremely low resistance. In most cases these diseases, such as smallpox and chicken pox, and the mass deaths they caused, travelled more quickly than the European explorers and thus preceded them in penetrating the hinterlands. Those who have read Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel will be familiar with this theory. It is interesting to note that it appears the recent H1N1 swine flu is hitting Native populations in Mexico and Canada much harder than others of European, African and Asian heritage, suggesting that even after several hundred years the American Natives are still at an immunological disadvantage. This is a controversial statement, but news releases by authorities such as WHO and Manitoba’s top doctor have said more or less the same thing.

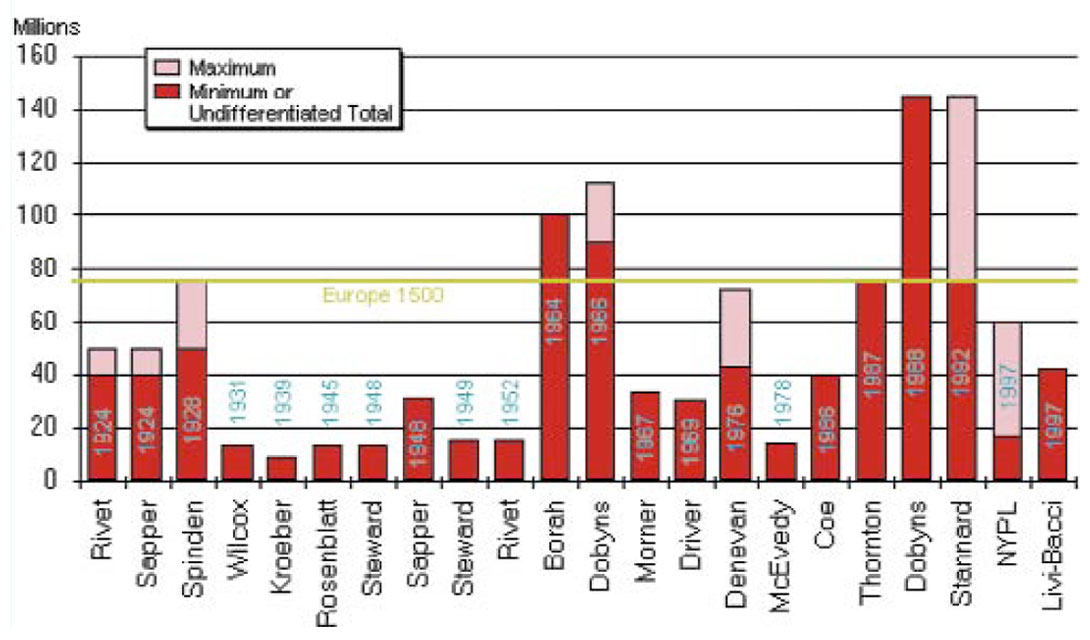

The question of how many Natives lived in the Americas at the time of first European contact is the most controversial area of this whole topic, and there really is no consensus, and there probably never will be. Figure 1 is a convenient graph I found on the Internet (copyright Matthew Wright, http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/20centry.htm) that summarizes various population estimates, with the most recent estimates on the right. Mann believes the evidence suggests numbers closer to the higher range, say 120 million, but I should emphasize that many other experts put their estimates much lower.

2) Native cultures were much more advanced and more diverse than previously thought. People mostly think of the cultures present in the Americas prior to European contact as being primitive, and of little interest other than the condescending type of interest “superior” cultures find in cultures they perceive to be less advanced than their own. Although these Native American cultures certainly were primitive compared to current ones, in some specific areas of mathematics, astronomy, agriculture (among others) they were the equals of contemporary European and Asian cultures, or perhaps even more advanced. For example, many consider the presence, size, and scope of a region’s empires as the measuring stick of cultural advancement; the Inca Empire at the time of Spanish conquest eclipsed all contemporary Empires around the world, including those in China and Europe.

3) Natives shaped the environments they lived in, often on a large scale, for their own benefit, much as humans have done in other parts of the world. This is directly in opposition to the popular view of the noble Native savage, living in harmony with nature. Some examples of environmentaltering technologies employed by American Natives include large scale irrigation, large scale burning, tree farming, large scale fish weir operations, development of modified plant species via selective breeding, large scale soil management, and so on.

An extremely interesting impact of this pre-European scenario that Mann describes is that it is at odds with many political points of view currently in vogue, and thus is likely to ruffle feathers and meet with hostility in many different camps. For example, Canadians of European heritage might subconsciously feel comfortable with the European influx to North America, because they believe it was not densely populated and the Europeans brought technologies that supported larger populations and better living conditions; they may feel threatened or less guilty by the notion that there were large numbers of Natives, and many of them lived in better conditions than people in Europe did at that time. Some sections describing the Natives’ view of these early Europeans as being smelly, unhygienic, unhealthy, malnourished, ugly little people are quite funny. And these same Europeans often marveled at the health, strength, size and physical beauty of the Natives. A big problem for early European communities in the Americas is that their members often “defected” and went “native”, since the living conditions among the Natives were often much more pleasant for many reasons. Nutritional experts believe the Natives’ diets were superior to those of contemporary Europe, and the political structures were certainly less rigid and more attuned to individual rights.

Environmentalists who romanticize that Natives were living in harmony with nature will be outraged by the notion that Natives were using large scale, ecosystem-changing technologies. The other side of this coin is that Natives themselves who have politically aligned themselves with the environmental movement will not like the idea that their historical cultures manipulated ecosystems as did the Europeans.

And of course there is the large ethical debate that each of us struggles with when we ponder the tragedy that the diseases our ancestors introduced wrought.

The Amazon Basin’s dark soils

But let’s move on to some more specific information. I chose the title terra preta for this article because it captures one example of how science is rewriting the pre-European history of the Americas. Terra preta, dark earth in Portuguese, is the name given to fertile, carbon-rich soils found widely throughout the Amazon Basin. Most tropical soils worldwide are leeched of nutritional components, and are very infertile. The creation and distribution of terra preta in the Amazon Basin was a mystery debated for a long time, but scientists now agree it is anthropogenic. It commonly contains potsherds and traces of organic human garbage, such as fish bones, fruit rinds, feces, etc. Chemical analysis shows elevated carbon content consistent with low temperature charcoal.

To get to the point, scientists now believe that between 450BC and 950AD the Amazon supported a widespread culture based on slash and char methods (as opposed to the wildly destructive and short term slash and burn method currently employed). These people would clear and burn the jungle, but in such a way as to create charcoal. When wood burns in a slow, oxygendeprived manner, charcoal is formed. Charcoal’s critical characteristic is that a high percentage of the original carbon remains trapped inside. The charcoal was then dug into the soil. Trees were selectively grown for their fruit, and plant crops were grown between the trees. (I am left with the question, what happened between 950AD and European contact? Perhaps a natural ebb and flow, rise and fall of cultures was at play?)

Soil scientists are discovering that charcoal used in this way has some remarkable properties. Instead of being washed away by tropical rains, nutrients bind to the charcoal, which essentially sequesters the organic carbon subsequently deposited, thus creating a positive cycle of soil enrichment. The Natives obviously enhanced this process by digging in their organic garbage. Of course we use this characteristic within many types of filters, where unwanted particles bind themselves to the charcoal inside the filter. The chemistry behind this is very interesting, and worthy of a closer study – 1491 has numerous references, and Wikipedia also covers the topic well with links to more in-depth sources of information.

Once created, terra preta continues to renew itself, so that now, even after over a thousand years has passed since its creation it is still very fertile, and is in great demand as a commercial product – companies dig it up and sell it. Estimates for the areal extent of this human-enhanced soil vary greatly, but the sum of all the little patches found throughout the basin, typically along rivers on higher ground, has been estimated as being one or two times the size of Great Britain! Another aspect to consider is the huge volume of pottery made and discarded over the centuries. The number of people and social cooperation required to achieve this is staggering, and totally at odds with the picture we have of the Amazon as a virgin, untrammeled wilderness populated by small numbers of Stone Age peoples in loin cloths.

The first European explorer to extensively travel the Amazon River, Francisco de Orellana in 1542/43, reported dense, continuous populations for hundreds of kilometers along the banks of rivers, but his accounts have been forgotten or widely dismissed as fabrications or exaggerations. Historians are now revisiting his reports and others’, assigning more value to them, and correlating them with the latest discoveries. One aspect of Amazonian tribes that has always puzzled anthropologists is that many display hierarchical aristocratic structures typical of settled societies and found nowhere else in the world among semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer societies. They now believe that the Amazon did indeed support many large and settled cultures, and what we see now is their cultural remnants, who, decimated by disease, scattered into the jungles and lost their more advanced and structured way of life. In other words the Amazonian Indians experienced a total societal collapse due to plagues introduced from Europe, and their cultures and technologies were lost and buried under jungles that have only recently grown back to what we believe is a primordial rainforest.

Fire

It appears that many of the technologies, if you can call them that, most commonly employed by Natives in both North and South America revolved around the use of fire. In North America there is a large archaeological record of cultures in the huge Mississippi / Missouri Basin, less so in the Appalachians, and science is revealing extensive use of fire as a means to shape the environment to human advantage.

Botanists and other scientists have come to the astounding conclusion that Natives in the greater Appalachian belt systematically burned out underbrush and unwanted trees, and selectively kept trees which produced a variety of nutritious tree nuts such as hickory and chestnut. It is estimated that when the Europeans arrived, one quarter of the trees between the St. Lawrence and Georgia were chestnut trees! The term “mast” is applied to nuts as a food base, and it was an essential part of the native diet in this part of the world. Early European settlers made numerous references to different types of food and drink the local Natives made from nuts. Beyond this selective promotion of useful trees they also artificially created an environment more likely to support larger game animals for them to hunt.

There is an interesting theory involving mast and passenger pigeons. Some ornithologists believe that the huge numbers of passenger pigeons in the earlier years of European settlement were the result of a temporary ecological imbalance. The passenger pigeon diet was also based on tree nuts. When disease wiped out most of the Natives who cultivated and ate the mast, the passenger pigeon numbers increased rapidly due to the sudden abundance of tree nuts. As the forests gradually returned to a more equal balance of tree species, and the new settlers hunted the pigeons in great numbers, their population declined. That, possibly combined with an introduced avian virus or disease of some sort, most likely led to their extinction. Note that it wasn’t just American humans who suffered plagues when the Europeans arrived – there were similar effects at play in the animal and plant worlds.

From the Great Lakes south there are many examples of different cultures, covering many thousands of years, many noted for the mounds they created. Some of the more famous mounds include the Newark Mounds and Great Serpent Mound, both in Ohio, Poverty Point in N.E. Louisiana, and the Cahokia Mounds in western Illinois, across the Mississippi River from downtown St. Louis. To create the mounds people excavated and moved huge volumes of near surface material. Soil scientists, paleobotanists, and pollen experts analyzing the mounds clearly agree that many or most of the mounds were surrounded by grassland, and there is evidence of large scale burning; this is in contrast to how “we” found these regions – covered in dense, apparently primordial forest. It appears as if these ancient peoples typically cleared and burned the areas around their settlements, to make room for farming, and to create conditions for larger game such as bison.

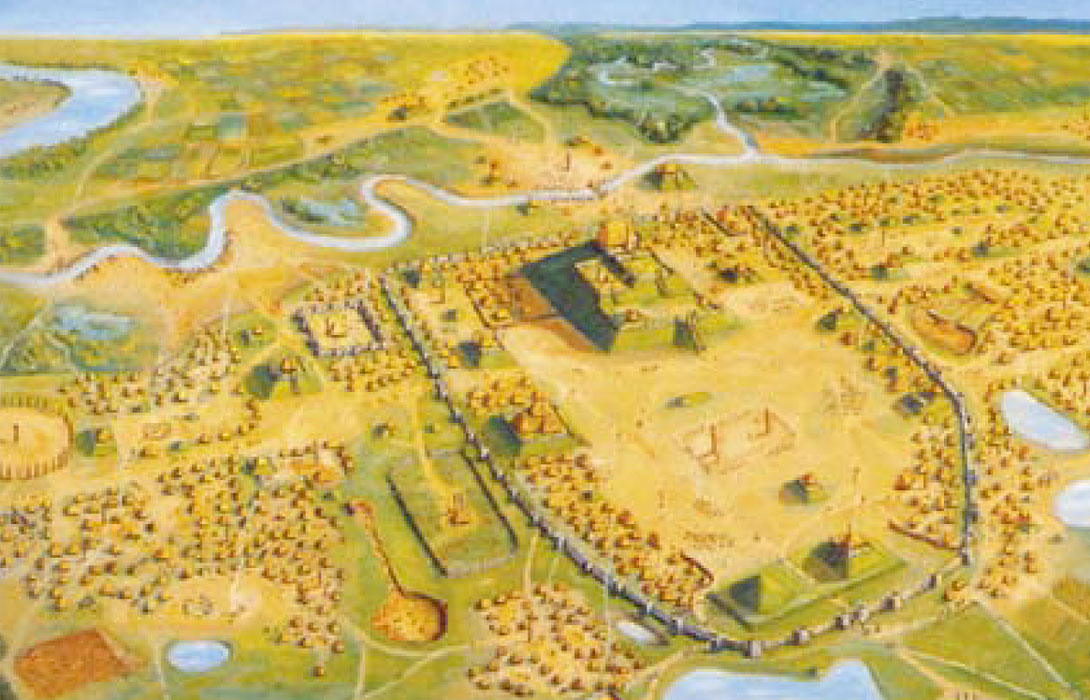

Maize (i.e. corn) was introduced to North America from further south some time after 1000 AD. In the period that followed, archaeologists can conclusively show there was widespread deforestation, as forests were cleared to make way for maize fields. It is believed that settlements were surrounded by maize fields of many square miles. Figure 3 is an artist’s rendition of what Cahokia might have looked like in its heyday; it was probably the largest North American city between 650 and 1400 AD. Figure 4 is an image of the great central mound today.

That takes me to my own conjecture regarding the Great North American Plains and bison numbers. I have heard theories that a combination of factors kept the prairie in a perpetual state of grassland - fires triggered by lightning, and the huge numbers of bison compacting the subsoil and eating tree shoots before they could mature. I always felt a bit skeptical about that. It’s pretty easy for trees to grow in many parts of the prairies. What if the Natives kept burning the prairies to promote the growth of grass and hence bison for them to hunt? What if bison numbers exploded as the Natives succumbed to the disease epidemics? What if the large herds of bison were a temporary imbalance as the passenger pigeon flocks are postulated to be?

Conclusion

I have only touched the surface of some of the topics that 1491 covers. One very interesting section deals with the high level of systematic selective breeding required to cultivate edible and nutritious corn in Mesoamerica. Another covers the very advanced irrigation techniques utilized by the Inca and their many predecessors. The theories put forth have ramifications in all sorts of areas of thought and study. I highly recommend 1491 to anyone interested in matters such as this. Before concluding however, I would like to touch on another book, totally nonscientific, which dovetails in a surprising way with 1491, and may give a hint of where the ongoing rethinking of ancient Native American history might lead us. I speak of A Fair Country – Telling Truths About Canada, written by John Ralston Saul. Saul, husband of former Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, is a left wing intellectual of a most infuriating sort – opinionated, given to hand-waving and pushing his own political agenda, etc., etc. For example, in one great leap of faith bereft of any logic, he puts forth one tier universal health care as a natural extension of Native culture! Huh? However, if you can see beyond those kinds of things, his book contains many tremendously insightful observations on how Native culture is an integral part of what we today call Canadian culture.

In the last section of 1491, entitled Coda, Mann attempts to describe ways the Natives lastingly influenced the nascent European-derived cultures in North and South America, particularly in the USA. In a prologue added to the most recent edition he laments the fact that he didn’t do a very good job in this section (and it indeed does seem short, not as detailed, and not as fully thought out and well-argued as other sections) and wishes he had spent more time on it. His Coda segues nicely with the central theme to Saul’s book, but the latter is limited to Canada.

I do think that the reevaluation, being driven by the sciences, of Native culture prior to European contact, will lead to intellectual reevaluations in the softer fields of history, law and politics, and that will ultimately result in us holding a different view of who we are as a nation and a culture. In other words, I believe what we are seeing in real time is how scientific discoveries are digested, filtered and ultimately absorbed into a mainstream culture’s definition of itself.

Share This Column