Who hasn’t, as a child at least, dreamed of living at the same time as some of the giants found in the fossil record? Think of dinosaurs, or some of the mega-mammals. The reality is, we do share this earth with a number of gigantic species, but they tend to live in environments people don’t frequent, such as the deep ocean, or in the soil. In this month’s article I will share some of my favourite giant species.

Gippsland Worm

When I first heard mention of this creature in Bill Bryson’s book on Australia, “In a Sunburned Country”, I was amazed, astounded; I half thought he was making it up or exaggerating. Investigations soon proved that this amazing species does exist, and it truly is a giant. The Gippsland Earthworm (Oligochaeta – megascolides Australis) is likely the world’s largest earthworm. It is found only in the Bass River Basin, which is in Gippsland, just east and a bit south of Melbourne, Australia, in south and west-facing river banks and hills.

This worm is usually two to three metres long, but the largest specimen measured was four metres long. As with any worm, they can stretch and contract considerably, which makes measurement highly subjective! Typical diameter is two centimeters. They live their entire lives underground in moist but not wet clayey soil, eating detritus. Their heads are purple, and their bodies pinkish-grey. On quiet nights one can occasionally hear them slurping and gurgling through their burrows.

Because the Gippsland worm is only found in such a small area, and doesn’t move very far, it is at high risk for extinction. They are also sensitive to changes in the water table, and easily killed by exposure to pesticides and herbicides. The good news is that farmers have found that they can make minor changes to their farming practices to make it a healthier environment for the worms, with no real negative impact to their farms’ yields or efficiencies. Australia is home to other giant worms, including the Terriswalkeris terraereginae, which grows up to 2m long, and is a gorgeous Prussian blue in colour. Unfortunately many of these native species are being pushed out by introduced European worm species. Closer to home are found the Oregon Giant Earthworm (Driloleirus macelfreshi), and the Giant Palouse Earthworm (Driloleirus americanus).

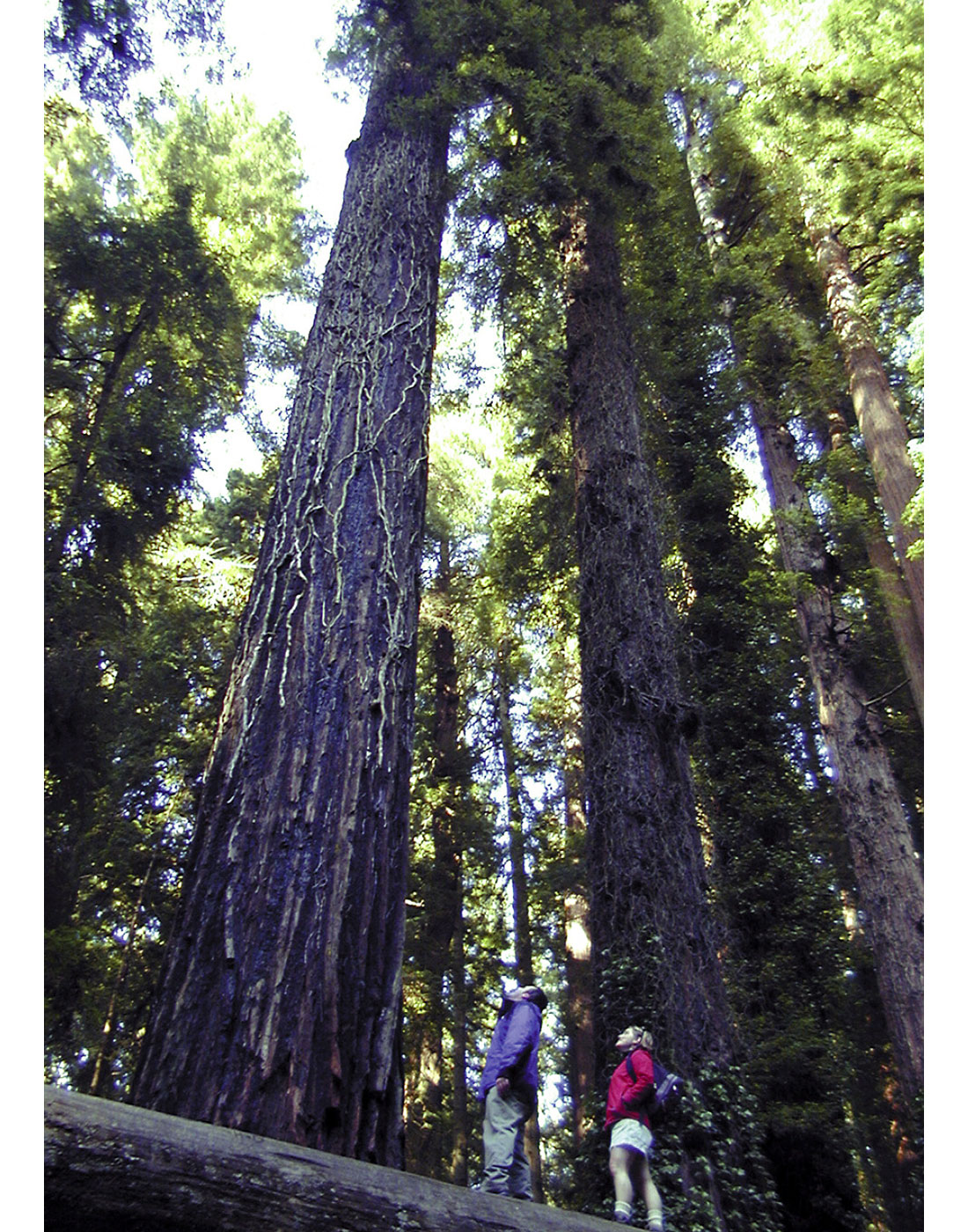

Sequoia

I believe large trees to be among the most magnificent and awe-inspiring organisms on Earth. The undisputed heavyweight champion among trees is the sequoia (Sequoia sempervirens), sometimes known as the Coast Redwood or California Redwood. These are the tallest known living trees. There are currently 33 sequoias living that exceed 110m in height. The tallest one is known as Hyperion and measures in at 115.5m. Most of the world’s tall trees have their own names, and in some parts of the world specific trees are held in spiritual reverence, and this is reflected in their names. Botanists have calculated a maximum height for any tree species of between 122 and 130 metres, based on the effects of gravity, and friction between water and the vessels it must move through within the tree. For comparison, Calgary’s 5th Ave. Place, Bow Valley Square and Petro-Canada East towers are all around 130m tall, give or take a few metres.

Sequoias also occupy a relatively small range, in this case a narrow 8 to 75 km coastal California strip 750 km long, with a northern extent just edging into Oregon. They live for an extremely long time, on average 600 years, but the oldest living one is ~2200 years old. Some reasons they are able to live so long and grow so big include:

- Sequoia bark is about one foot thick, making them fire and bug resistant.

- They have very low resin levels, making them less flammable than most trees.

- Foliage on mature trees is high up enough to avoid being burned in forest fires.

- The environment they live in has extremely high rainfall, up to 2.5m annually.

Sequoias reproduce either via winged seeds or asexually via buds which form below the bark on dying trees. This latter mechanism results in straight lines of new trees which have sprouted from a fallen tree, or “fairy” rings which have sprouted around the trunk of a tree which died still standing. Once seeded they grow very rapidly, up to 20m in twenty years. This means California is able to maintain a viable and valuable redwood lumber industry from new growth trees, and the wood is highly prized for its colour, grain, and durability.

There is an interesting subculture of tall tree climbers who locate, climb and measure extremely large sequoias (and presumably other tall trees around the world). They keep the location of their discoveries secret, especially if they are located in or near designated logging zones. It is not unusual for giant sequoias in protected areas to be “accidentally” felled by loggers. These climbers use special techniques similar to rock climbers, and will pull a straight rope from ground level up to the tip of the crown to accurately measure the height of a tree. For a fascinating article on this topic, see “Climbing the Redwoods” by Jack Lindsay in the Feb. 14, 2005 issue of The New Yorker magazine.

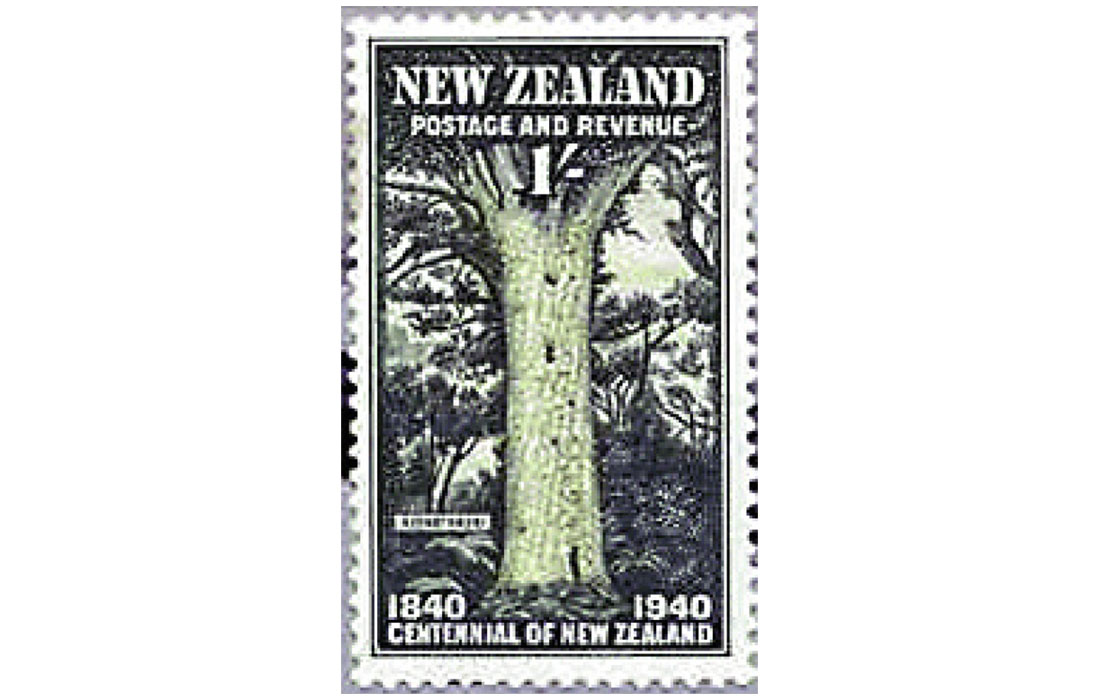

The tallest known and documented non-Redwood tree is a member of the species Eucalyptus regnans growing near Hobart, Tasmania that is 40cm shy of 100m. I have seen recent reports of 101m tree of the same species, and there are persistent rumours of eucalypts exceeding the sequoias in height, but I do not believe any of them have been proven. Other personal big tree favourites of mine include New Zealand’s kauri tree and Africa’s baobab (some baobab species are also found in Madagascar and Australia). Kauris, while not that tall (about 50m maximum), are massive in volume because of their stout trunks. Figure 3 shows Tane Mahuta, “Lord of the Forest” in Maori, the largest known kauri and New Zealand’s most famous tree. Most baobab species are short, but they can be enormous in girth, with diameters up to 11m; they are also unusual in that their trunks are fibrous and pulpy, not rigid, and swell during the rainy season to store up to 120,000 litres of water.

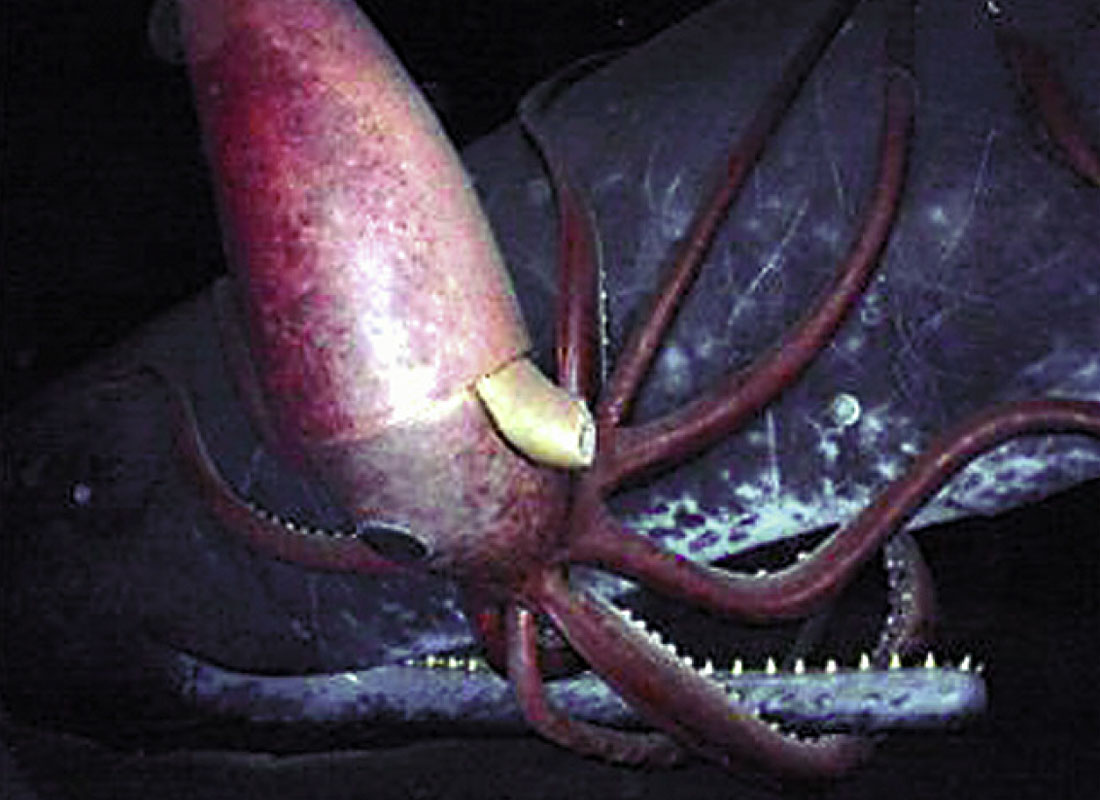

Giant squid

Ah, the giant squid, Architeuthis – what can I say about this magnificent creature, so unusual and mysterious? I just love this creature. For something so large it is amazing that there remain so many question marks surrounding it. For example, zoologists have no idea whether it is a lethargic, passive hunter that lazily grabs prey that swims by, or an aggressive, fast-moving terror occupying top spot in the deep abyssal food chain. I highly recommend “The Search for the Giant Squid” by Richard Ellis. I offer some highlights from that book here.

Giant squid are cephalopods, as are all squid. The word means “head-footed” in Greek. This because the order of body parts – torso-head-limbs – is different than the head-torso-limbs configuration most other creatures possess. In other words, the squid’s eight arms and two tentacles are attached to its head. Scientist have speculated that of all the species found on Earth, the squid family makes up largest volume of biomass; under the ocean waves there exist six or seven hundred different species of squid of all different sizes, and immense numbers. The giant squid happens to be one of the biggest (the Colossal Squid is thought to be larger, but even less is known about it). Just how big? The largest documented architeuthis specimen was a 57 foot one that washed up on New Zealand’s shores in 1887, and it weighed about a ton. Because there have been so few actual specimens measured, scientists speculate that it is statistically probable that they grow much larger, and comparisons of the sizes of sucker marks found on sperm whales support this.

Architeuthis lives and hunts at depths between approximately 200m and 700m, and the specimens found occasionally at the surface are usually dead, sometimes dying, and more often than not already in bits. They eat fish, octopus, prawns and other squid. Because like all squid their food passes through the brain area to get to their stomachs, they must chop up their food into small pieces with their powerful beaks. Their two eyes are the size of dinner plates, designed to catch the little light that penetrates to those depths. Instead of using an iron compound in their blood to carry oxygen, they use a copper compound, giving their oxygenated blood a slight bluish hue.

The only skeletal structure architeuthis possesses is afforded by cartilage-like material. As a result it is likely that they are able to grow extremely quickly – some scientists hazard a guess that they are close to full grown in two years or so – but it also means their bodies decompose quickly. They are jet propelled and highly manoeuverable – they suck in water and then shoot it out through a siphon which can be pointed in any direction. They have suction cups on their eight arms with which to catch and hold their prey, and s ome t h i n g like a grappling hook on the end of each of the two tentacles, which they can presumably shoot out quickly.

I say presumably, because no one has ever seen a giant squid in its natural environment. For the most part scientists compare architeuthis physiology with that of smaller squid species, and then make conjectures. One thing that is known is that architeuthis has a hunter – prey relationship with the sperm whale that defines its existence. Figure 4 is a picture of an exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Ocean Life. My apologies, but the few actual architeuthis photos available show lifeless blobs of gelatinous mass lying on ship decks, hardly doing justice to these incredible creatures.

Whalers for years have found pieces of giant squid in the bellies of sperm whales, and scientists learn a lot by analyzing whale stomach contents. Because squid beaks don’t dissolve, we have a good idea what sperm whales eat in terms of squid. It looks like they primarily eat smaller squid, but if they happen to run into a giant one, the battle is worth the large meal. Almost all sperm whales exhibit sucker marks made by architeuthis. An interesting side note involves the way sperm whales hunt and feed. It appears as if they use a “sonar cannon” to temporarily stun squid. They produce, focus and emit a powerful sonic blast via their enormous foreheads. The stunned squid drop to the ocean floor, where they are dredged up by sperm whale’s enormous, shovel-like lower jaw. Sonar images of the sea floor in areas where sperm whales are known to hunt reveal linear gouges in the sea floor mud.

Scientists believe that the sperm whale brain is the largest of any animal ever to have lived, and the giant squid brain is also very large, so these deep water tussles may be quite cerebral. Many squid ganglia appear to be related to sensory functions, so this brain power may not be used towards intelligence in the human sense. It is thought that in general all squid possess sensory receptors for vibration and smell all over their bodies. They also exhibit the ability to change their appearance dramatically via different colours and patterns. It is thought they use this to communicate, and to confuse predators and prey. Many species are capable of luminescence, so for deeper water species this opens the possibility that they light up their undersides to appear invisible against the distant light from the surface to anything below. Even more fascinating, there are hints that some squid, including architeuthis, possess photo-transmitting cells around their eyes that could act as searchlights! That conjures up an eerie vision – an enormous 60-foot predator scouring the murky depths with a giant spotlight eye!

Conclusion

There are many, many giant species making this planet a more interesting place, and I would love to go into detail on each one of them. There is also a variety of ways to measure size, and so there are many organisms that one could call giant. For example, there are stands of aspen over 100 acres in area that are connected by a single root system, and each tree in the stand is genetically identical. Similarly, some single fungus specimens can cover huge areas. But these examples don’t have the appeal of the large single trees or animals. Here are a few more my gigantic favourites, with key details on each.

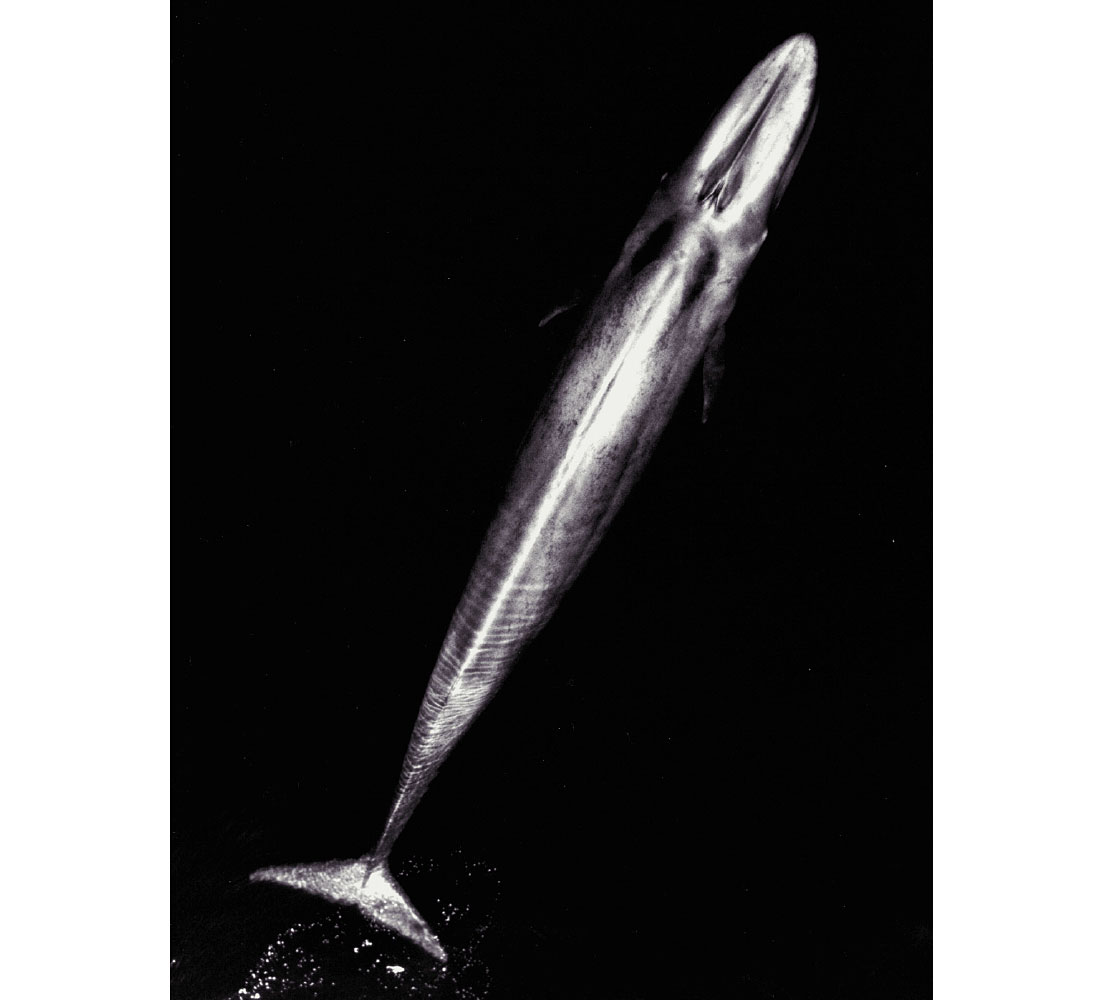

Blue whale

- Balaenoptera musculus – largest animal ever known to have lived.

- Almost hunted to extinction, very slow recovery in numbers.

- Small pods scattered around the world’s oceans.

- 190 ton total weight; 3 ton tongue, 600 ton heart.

- Full grown length over 30m.

- Can swim at over 30 km/h.

- Krill eater.

- See article in March, 2009 National Geographic magazine.

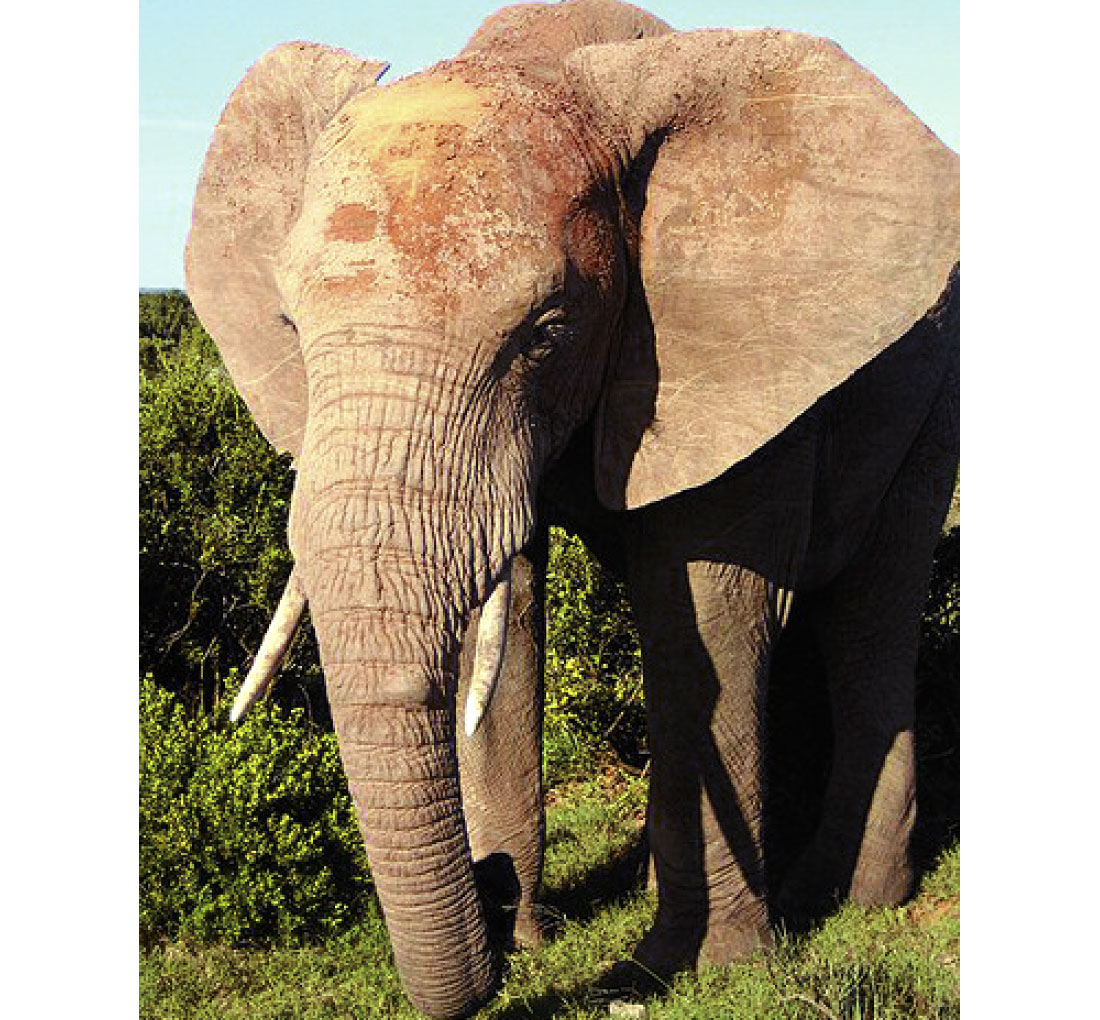

African elephant

Genus Loxodonta; two species: africana (bush) and cyclotis (forest).

- Largest currently living land animal species.

- Largest currently living land animal species.

- Length 6m to 7m. • Shoulder height over 3m.

- Typical weight 6,000 Kg to 9,000 Kg.

- Largest male bull weight recorded was 12,274 Kg.

- Appears to communicate at infrasound level (< 20Hz.)

- Threatened by poaching for tusks, meat.

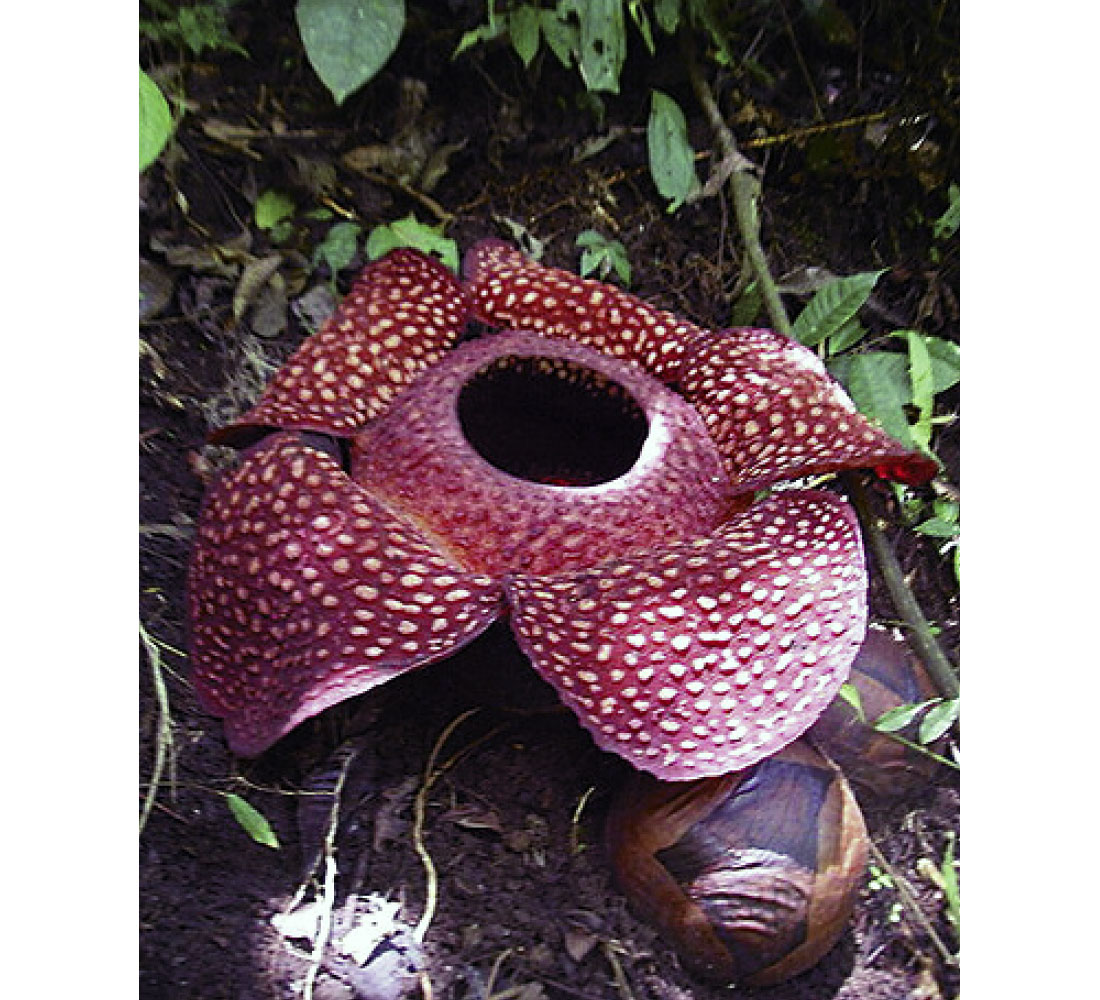

Rafflesia

Genus of parasitic flowering plants named after Sir Stamford Raffles.

- Found throughout the jungles of S.E. Asia.

- Rafflesia arnoldii is the largest single flower, by weight.

- A single flower can grow to 1m in diameter, and 11 Kg in weight.

- Sometimes called the “corpse flower” because it smells like rotting flesh.

- Some species endangered, mainly due to loss of habitat to logging.

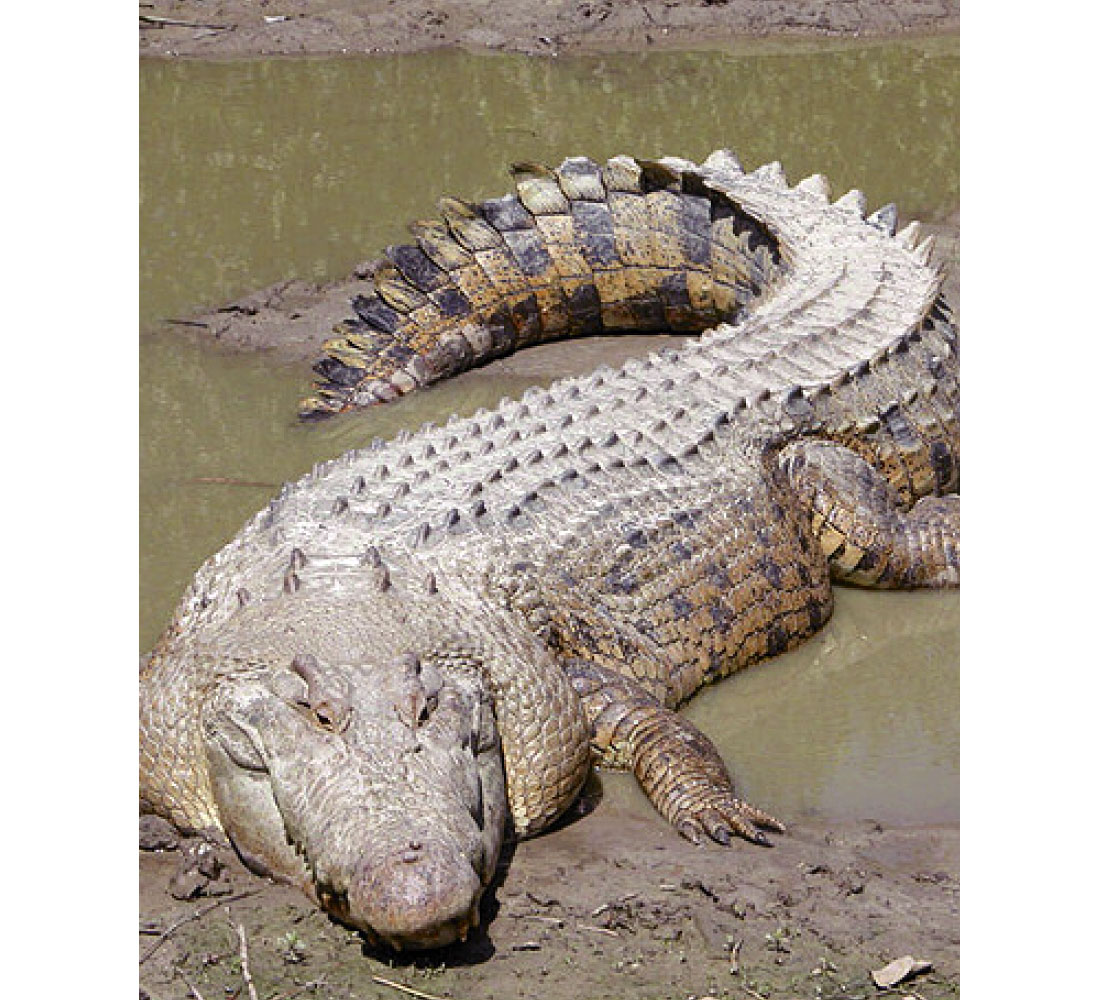

Estuarine crocodile

Crocodylus porosus – largest currently living reptile species.

- Full grown males measured between 6m and 7m.

- Many unsubstantiated claims of lengths up to 11m or 12m.

- Incredible bite force of over 2000 Kg.

- Found in coastal areas from northern Australia up to east coast of India.

- Populations endangered or extinct in some places, healthy in others.

Flying foxes

- World’s largest bats.

- Many species within the genus Pteropus.

- Pteropus vampyrus has the largest wingspan, 2m.

- Many have wingspans of ~1m, similar to a large human male’s outstretched arms.

- Only eat fruit and pollen.

- Don’t use echolocation, just sight and smell.

- Many species endangered – habitat loss, hunting.

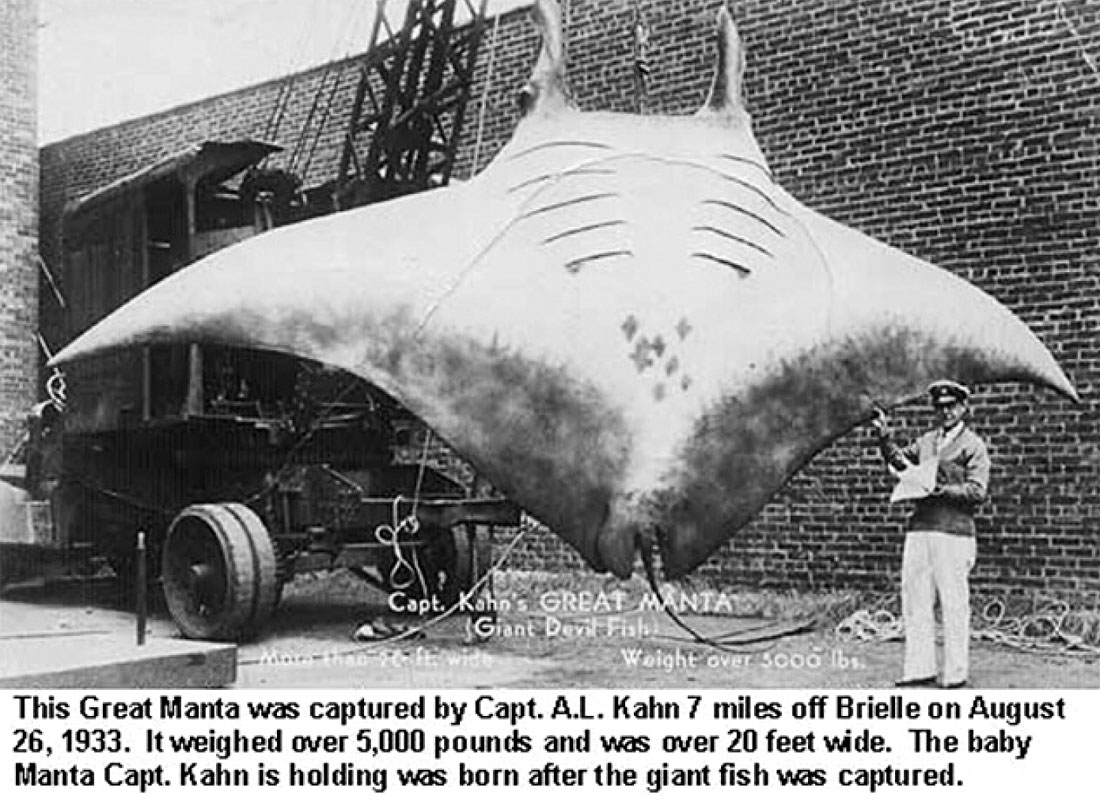

Manta ray

- Single species is Manta birostris, likely to be revised to three species.

- Found in all of Earth’s tropical waters.

- Can grow to 8m width, 2300 Kg.

- Plankton eater – vestigial teeth are hidden and useless.

- Unlike other rays, no barbed tale.

- Curious and friendly around humans.

- Human touch can damage mucus coating, leading to infection and disease.

- Generally healthy numbers, but overfished in some areas.

So you see, we really do share our planet with giants, many of whom rival those found in the fossil record. The sad thing is that being so big makes them very vulnerable to extinction for many reasons. Their size typically requires a large territory and / or large quantities of resources within their natural environment, and this often brings them into direct competition with not the planet’s biggest ape, but certainly its smartest and stupidest, the human.

Share This Column