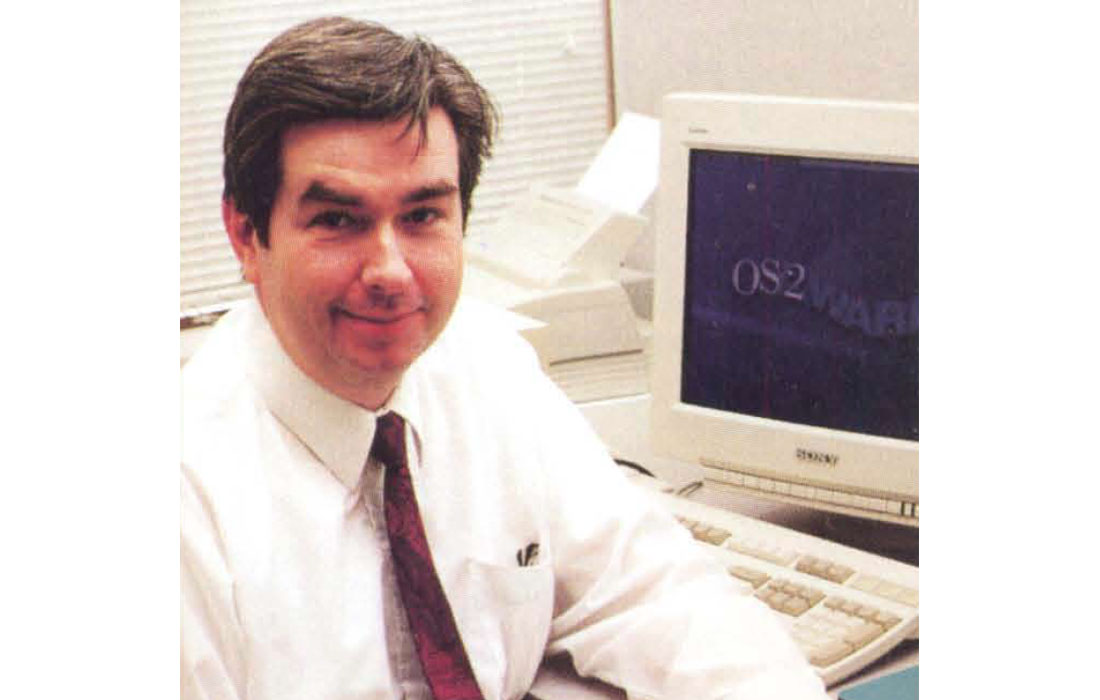

Word on the street has it that geophysicist Allan Bradshaw has been akin to the Wayne Gretzky of the seismic processing world. When confronted with such rumor, Bradshaw quietly states that such comparison is very flattering, "but in terms of hard work, dedication and depth of accomplishment, I think I am a bit like Gretzky."

The middle child with an older sister and a younger brother, Bradshaw was born March 23, 1948 on a small grain and mixed farm near Innisfail, Alberta. His recollections of his early childhood conjures up visions of living on a farm with no running water, a wooden stove, and light powered by a 12 volt electrical generator driven by a windmill.

When Bradshaw was four years old, the family moved to Calgary where his father who had worked part-time for CP airlines (now Canadian) as an aero-frame mechanic found work on a full-time basis. He grew up in the Killarney neighborhood, a few blocks from the horse stable where the Westgate Hotel is now. He attended the old sandstone Central High School before it was closed, then went to Western Canada High School, where he graduated with honors in 1966.

"During elementary school, I was slow at learning reading, but I liked art and math," recalls Bradshaw. "At high school, I tried to emulate the better students, I was always trying to do what they could do. In physical education, I always tried to run with Bill Boei because he was the fastest."

During high school, Bradshaw excelled in mathematics and physics, and speaks fondly of George Bayliss, an old seasoned English teacher. His high school graduation was particularly memorable because he had arrived late for the ceremony. As the last one to cross the stage, "I received the longest and loudest round of applause."

After high school, Bradshaw enrolled at the University of Calgary to study mathematics and physics. By second year, he realized that "astro-physics was too quirky for me and thought since I started university, I should persevere, specializing in acoustics in the final year."

While attending university, Bradshaw held summer jobs working in a sheet metal shop, where one of his duties was to cut and install asbestos insulation in steel fire doors. At that time, it was not generally known that working with asbestos was such a dangerous thing to do. Just for fun, he designed and built his own analog tape recorder.

"Going to university was okay because there was this theoretical challenge, but university did not teach me anything about being successful in the practical world."

A soft-spoken mild-mannered man, Bradshaw professes to have become idealistic after university and says of himself, "I'm probably not real smart, but I make up for it by really applying myself. I think insight, like intuition, is really important, but insight takes effort. "

With respect to geophysics, he likes to think things through for a long time to make sense of the situation. "I also have a drive to make things Simpler and to pass that information on. I'm pretty opinionated against making things more complicated than they should be, like Microsoft Windows. Whenever possible people should strive for simplicity and elegance, and that brings back the true admiration I feel for people like Einstein," explains Bradshaw.

After graduating with his honors B.Sc. in 1970, Bradshaw passed up the choice to be a meteorologist in Antarctica to participate in the emerging field of geophysics. He called up Don Propp, then the president of Northern Geophysical, who offered him a job. Hired on as a "junior computer", he started off working on the seismic crews beginning with planting geophones in varied topography, from northern Alberta muskeg to Grand Prairie hot summer to chilling winter of Rocky Mountain House. " It was a great experience," he recalls. "Not many people have seen an ana log vibroseis correIator in action." He then worked in Northern Geophysical's small processing group where they used blocked-time at Digitech on EMR computers. He remembers spending one winter sorting out a room full of Carter analog tapes. This task was the start of his data processing years when he learned that, "Computers are cold and unforgiving (and that's not just the air conditioning). Just one wrong number could waste hours of computer time. This would have to change."

In 1973, Northern Geophysical's seismic group was taken over by Geo-X Systems, which then occupied two apartments in London House. Geo-X, then a small processing company immediately doubled its staff to eight persons. It was while working for Geo-X that Bradshaw further developed his seismic processing skills while he wrote applications software and trained the staff. In 1978, Bradshaw was promoted to vice-president of production.

Don Chamberlain, then president (now CEO) of Geo-X Systems gave Bradshaw an incredible opportunity to learn as he developed the company's proprietary software. Bradshaw quips, "Software has got to be reliable and something you could count on."

For a moment, he muses to himself about an incident that occurred while working for Geo-X Systems in the downturn of 1986. At that time, there was only a sole marine project to bid on. Ken Gillespie at Pulsonic had mentioned to Bradshaw that they had the software for the project but no hardware. Geo-X had the hardware, but no software. They both went to bid and Geo-X got the job. "That was one incredible push. I was writing the software, trying to keep a couple weeks ahead of when the guys needed it," Bradshaw recalls.:

In 1988, when Bradshaw turned 40 years of age, he reached his "male climacteric." He sold his Corvette to buy a plotter, quit his job at Geo-X and took time off to think about life and visit a lady friend living in Vancouver. During Bradshaw's employment at Geo-X, the company had grown to employ over 100 persons and during that time, "we were able to grow from a few rooms in London House to three floors at Esso Plaza."

While Geo-X had garnered a reputation of being somewhat a sweatshop, Bradshaw says, "It was really quite an environment to see that growth and that group of people with that morale. I worked long hours down with the troops, and would try to bring out the best in them, even if they didn't want me to." The 1986 oilpatch crisis left a bittersweet taste for Bradshaw who disliked downsizing staff.

"In hindsight when I look back, relatively speaking, I learned more in the next ten years than I had in the previous twenty. There's always an opportunity to learn if you want to dig into things, and it can be anything from low-level device drivers to advanced signal theory. The 40's (age-wise) have been my most productive years."

In 1989, Bradshaw set up Amber Systems, which provides geophysical consulting. He started working on little projects, writing data analysis programs for field instruments, tape re-formatting, plotting and a refraction analysis program for near surface engineering. "PC's were coming on their own and I wanted to explore this avenue even though people in the industry still had a stigma about their usefulness." Steve Fuller from Earth Signal Processing encouraged Bradshaw to write a complete seismic processing package for the PC, something no one else seemed to want to tackle.

"I like a challenge," says Bradshaw. "I'm the kind of guy who grabs a hold of something and goes forward. "

Writing the software took several years of long hours and late nights but he enjoyed working in the home environment with the good company of his helpers "Rabbit and Junior. "

From the development of software programs, he has seen technology evolve in the seismic world. In the 1970's, Bradshaw developed Fortran programs for Raytheon mini-computers, with only 32 KB of main memory. In the 1980's, he worked on many application programs on IBM mainframes with a then generous 32Mb of memory, but that came with a hefty price tag (the memory alone was a million dollars).

"Seismic processing development has always demanded more power, speed and capacity than what is currently available. That's partly what makes it exciting, and solving problems that never quite fit the hardware requires creativity and innovation." With the 1990's, came the real potential of the personal computer, which brought ever-increasing speed and capacity at more and more affordable prices. " It was with a design philosophy of elegance and simplicity that I put together a new system on this platform, with a new language, i.e. C, and focusing on making the key algorithms better geophysically. To make the human interface easier, I also wrote a specialized language that manages all the details of the processing yet remains under the control of the user."

This current system for processing 2D and 3D is being used at Earth Signal Processing on personal computers running under IBM OS/ 2. It has met with great success on projects in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. " It's really rewarding to get feedback from clients with drilling successes of five out of five and four out of four. It's just the start of more good things to come, because responding to client's changing needs is a big part of the development process."

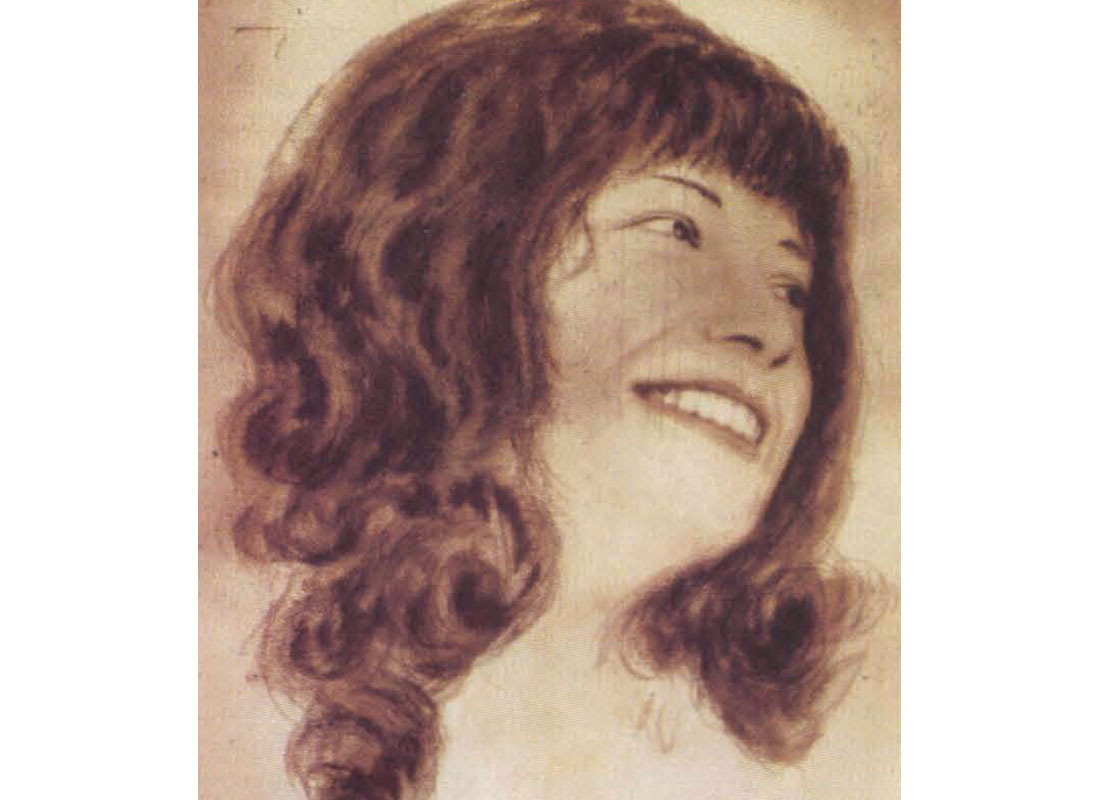

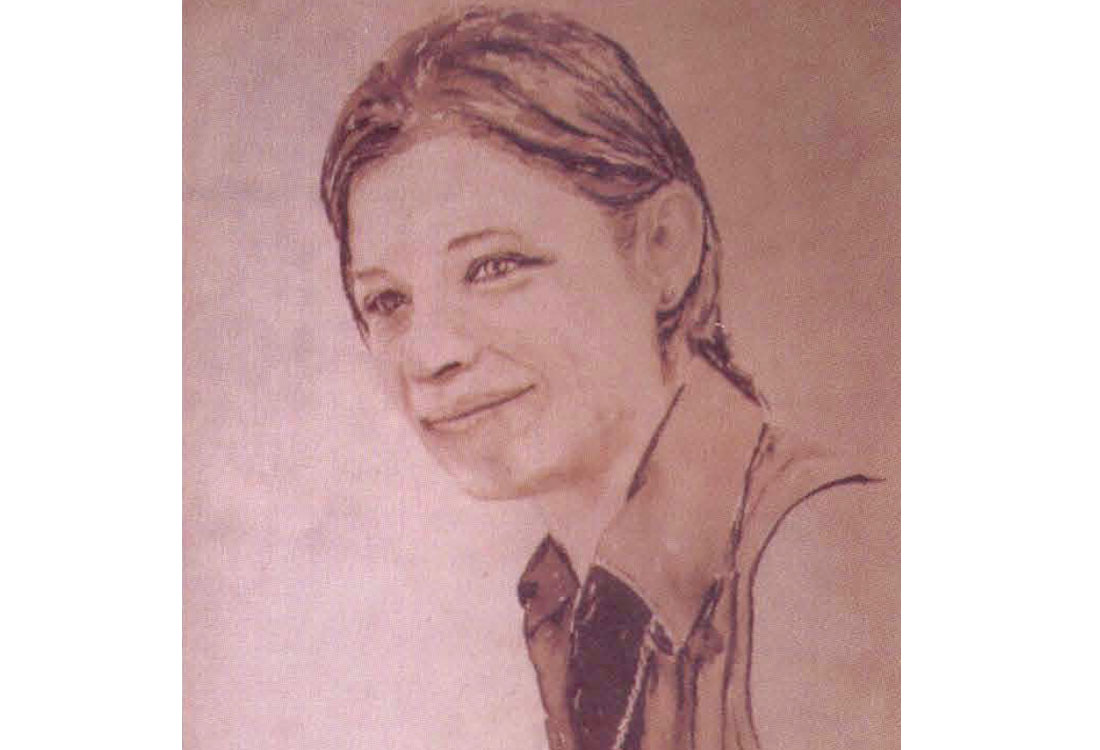

Bradshaw is an active member of APEGGA, the CSEG and the SEC. After geophysics and mathematics, he shares a passion for art, being an accomplished portrait painter, favoring the media of sepia ink on canvas. While consulting keeps him very busy, and his work leaves him little spare time for life's other pleasures, like painting or hi king, he has managed to devote some time for charitable work in the community, especially for the Alberta Lung Association.

"There are not many jobs that combine science, technology, creativity and a sense of accomplishment." Paraphrasing Gretzky, Bradshaw says, "Seismic is the greatest game in the world and I feel privileged to be part of it."

Share This Column