Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was in many ways the poster child used for global warming by climate change environmental activists. In terms of overall hurricane activity (number and intensity of storms), the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active season ever recorded. However with the global economic downturn the wind came out of sails – so to speak – in terms of the impetus placed on the issue of climate change. Global treaties and conferences failed to produce much in terms of real results as different countries sought to advance their own agendas. The Earth’s biosphere is infinitely complex and predicting what will happen in the future remains largely in the realm of perception and educated guessing. Meteorologists have a difficult enough time with predicting weather accurately past a few days from the current day.

Interestingly enough, The Economist recently wrote a couple of articles on the matter. I have put together pieces of both articles in the following column.

The Economist – Mar. 30th 2013

“Apocalypse perhaps a little later – Climate change may be happening more slowly than scientists thought. But the world still needs to deal with it.” (excerpts in blue)

Climate science – A sensitive matter “The climate may be heating up less in response to greenhouse- gas emissions than was once thought. But that does not mean the problem is going away.” (excerpts in brown)

“IT MAY come as a surprise to a walrus wondering where all the Arctic’s summer sea ice has gone. It could be news to a Staten Islander still coming to terms with what he lost to Hurricane Sandy. But some scientists are arguing that man-made climate change is not quite so bad a threat as it appeared to be a few years ago. They point to various reasons for thinking that the planet’s “climate sensitivity”— the amount of warming that can be expected for a doubling in the carbon-dioxide level—may not be as high as was previously thought. The most obvious reason is that, despite a marked warming over the course of the 20th century, temperatures have not really risen over the past ten years.”

“OVER the past 15 years air temperatures at the Earth’s surface have been flat while greenhouse-gas emissions have continued to soar. The world added roughly 100 billion tonnes of carbon to the atmosphere between 2000 and 2010. That is about a quarter of all the CO2 put there by humanity since 1750. And yet, as James Hansen, the head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, observes, “the five-year mean global temperature has been flat for a decade.”

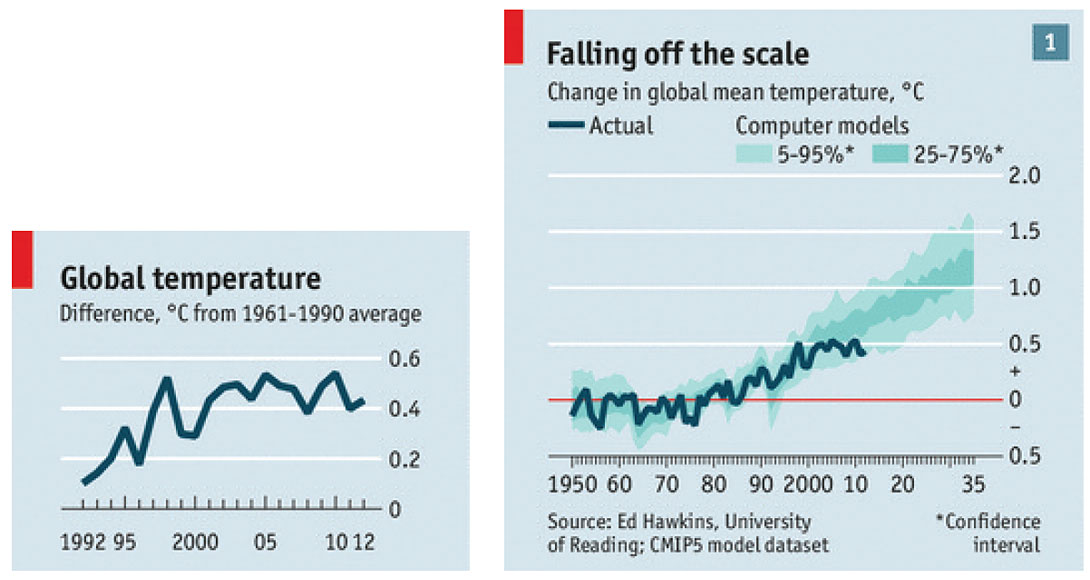

Temperatures fluctuate over short periods, but this lack of new warming is a surprise. Ed Hawkins, of the University of Reading, in Britain, points out that surface temperatures since 2005 are already at the low end of the range of projections derived from 20 climate models (see chart). If they remain flat, they will fall outside the models’ range within a few years.

The mismatch between rising greenhouse-gas emissions and notrising temperatures is among the biggest puzzles in climate science just now. It does not mean global warming is a delusion. Flat though they are, temperatures in the first decade of the 21st century remain almost 1°C above their level in the first decade of the 20th.

The mismatch might mean that—for some unexplained reason— there has been a temporary lag between more carbon dioxide and higher temperatures in 2000-10. It might be that the 1990s, when temperatures were rising fast, was the anomalous period. Or, as an increasing body of research is suggesting, it may be that the climate is responding to higher concentrations of carbon dioxide in ways that had not been properly understood before. This possibility, if true, could have profound significance both for climate science and for environmental and social policy.”

“It is not clear why climate change has “plateaued”. It could be because of greater natural variability in the climate, because clouds dampen warming or because of some other little-understood mechanism in the almost infinitely complex climate system. But whatever the reason, some of the really ghastly scenarios—where the planet heated up by 4°C or more this century—are coming to look mercifully unlikely. Does that mean the world no longer has to worry?

No, for two reasons. The first is uncertainty. The science that points towards a sensitivity lower than models have previously predicted is still tentative. The error bars are still there. The risk of severe warming—an increase of 3°C, say—though diminished, remains real. There is also uncertainty over what that warming will actually do to the planet. The sharp reduction in Arctic ice is not something scientists expected would happen at today’s temperatures. What other effects of even modest temperature rise remain unknown?

The second reason is more practical. If the world had based its climate policies on previous predictions of a high sensitivity, then there would be a case for relaxing those policies, now that the most hell-on-Earth-ish changes look less likely. But although climate rhetoric has been based on fears of high sensitivity, climate policy has not been. On carbon emissions and on adaptation to protect the vulnerable it has fallen far short of what would be needed even in a low-sensitivity world. Industrial carbon-dioxide emissions have risen by 50% since 1997.

Any emissions reductions have tended to come from things beyond climate policy—such as the economic downturn following the global financial crisis, or the cheap shale gas which has displaced American coal. If climate policy continues to be this impotent, then carbon-dioxide levels could easily rise so far that even a low-sensitivity planet will risk seeing changes that people would sorely regret. There is no plausible scenario in which carbon emissions continue unchecked and the climate does not warm above today’s temperatures.”

“Other recent studies, though, paint a different picture. An unpublished report by the Research Council of Norway, a government-funded body, which was compiled by a team led by Terje Berntsen of the University of Oslo, uses a different method from the IPCC’s (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). It concludes there is a 90% probability that doubling CO2 emissions will increase temperatures by only 1.2-2.9°C, with the most likely figure being 1.9°C. The top of the study’s range is well below the IPCC’s upper estimates of likely sensitivity.

This study has not been peer-reviewed; it may be unreliable. But its projections are not unique. Work by Julia Hargreaves of the Research Institute for Global Change in Yokohama, which was published in 2012, suggests a 90% chance of the actual change being in the range of 0.5- 4.0°C, with a mean of 2.3°C. This is based on the way the climate behaved about 20,000 years ago, at the peak of the last ice age, a period when carbon-dioxide concentrations leapt. Nic Lewis, an independent climate scientist, got an even lower range in a study accepted for publication: 1.0- 3.0°C, with a mean of 1.6°C. His calculations reanalysed work cited by the IPCC and took account of more recent temperature data. In all these calculations, the chances of climate sensitivity above 4.5°C become vanishingly small.

If such estimates were right, they would require revisions to the science of climate change and, possibly, to public policies. If, as conventional wisdom has it, global temperatures could rise by 3°C or more in response to a doubling of emissions, then the correct response would be the one to which most of the world pays lip service: rein in the warming and the greenhouse gases causing it. This is called “mitigation”, in the jargon. Moreover, if there were an outside possibility of something catastrophic, such as a 6°C rise, that could justify drastic interventions. This would be similar to taking out disaster insurance. It may seem an unnecessary expense when you are forking out for the premiums, but when you need it, you really need it. Many economists, including William Nordhaus of Yale University, have made this case.

If, however, temperatures are likely to rise by only 2°C in response to a doubling of carbon emissions (and if the likelihood of a 6°C increase is trivial), the calculation might change. Perhaps the world should seek to adjust to (rather than stop) the greenhouse-gas splurge. There is no point buying earthquake insurance if you do not live in an earthquake zone. In this case more adaptation rather than more mitigation might be the right policy at the margin. But that would be good advice only if these new estimates really were more reliable than the old ones. And different results come from different models.”

“Bad climate policies, such as backing renewable energy with no thought for the cost, or insisting on biofuels despite the damage they do, are bad whatever the climate’s sensitivity to greenhouse gases. Good policies— strategies for adapting to higher sea levels and changing weather patterns, investment in agricultural resilience, research into fossil-fuelfree ways of generating and storing energy—are wise precautions even in a world where sensitivity is low. So is putting a price on carbon and ensuring that, slowly but surely, it gets ratcheted up for decades to come.

If the world has a bit more breathing space to deal with global warming, that will be good. But breathing space helps only if you actually do something with it.”

From the Thursday Files

Surely, if Mother Nature had been consulted, she would never have consented to building a city in New Orleans.

– Mortimer Zuckerman

Nature is regulating our climate for free. Mother Nature, she’s been doing that for free, for a long, long time. Now do you really want to get in there and do geo-engineering and all this kind of stuff?

– Thomas Friedman

Share This Column