And now for something a bit different….Over the years I have jokingly referred to my friends in the Oil Companies as “Big Oil” as method for differentiation between what we do as a Seismic Association in our advocacy role and what they do with the newfound power of Oil. Nowadays the terminology seems to be everywhere. So to set the record straight I will spend the time in this column talking about “Really Big Oil”. These are in fact the sluggish National Oil Companies (NOC’s) – the behemoths that control virtually all of the world’s oil. In attribute to The Economist, many of these facts and ideas come from a couple of their August editions.

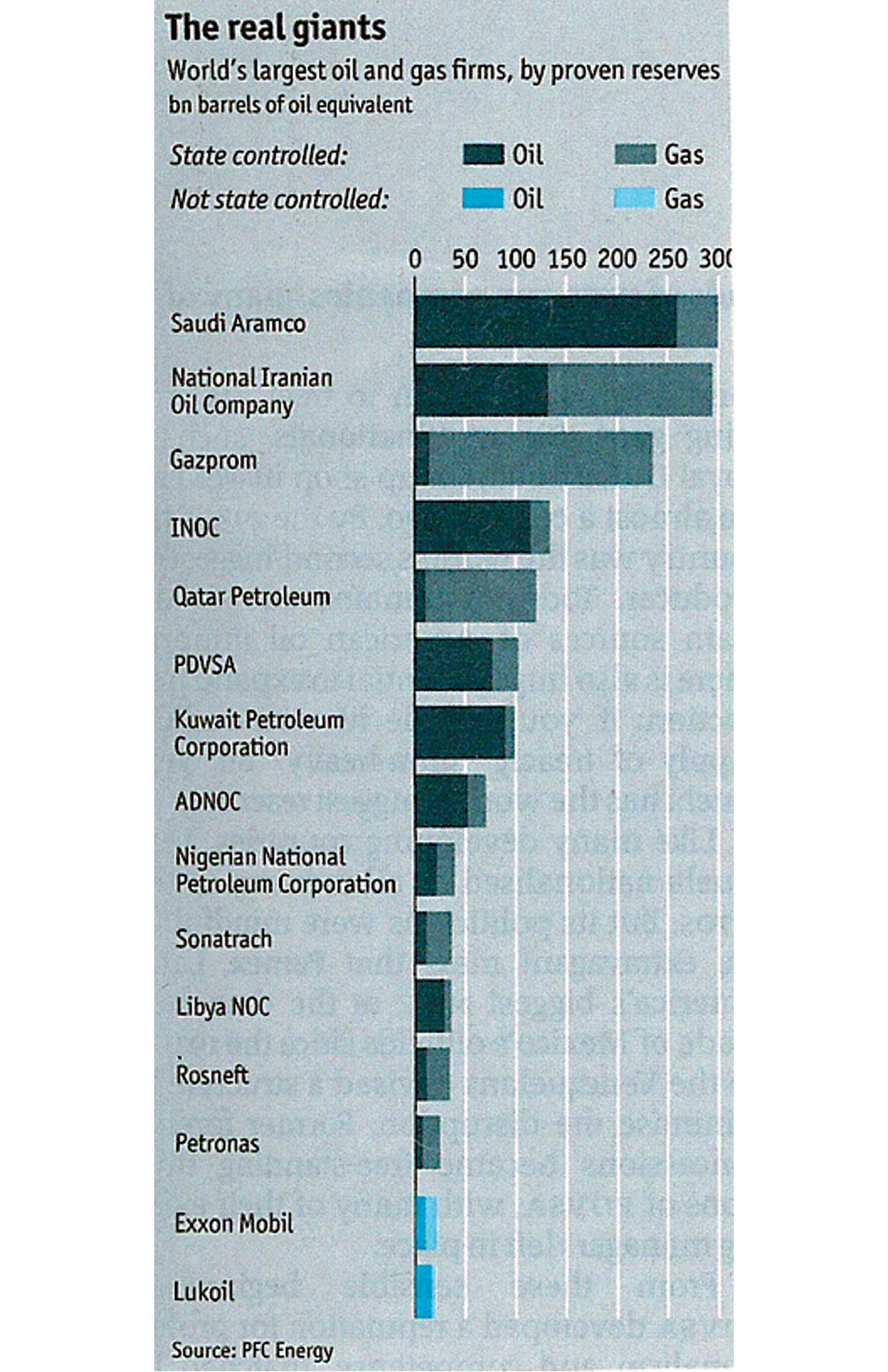

Exxon Mobil is the world’s most valuable listed company with a market capitalization of $412 billion. But if you compare oil companies by what they have left in the ground Exxon is a distant fourteenth – the thirteen larger companies are state owned through which profits are retained by the ruling government.

Our modern day Oil Companies are small compared to the NOC’s owned or controlled by governments of oil-rich countries. The NOC’s in fact control 80 to 90 % of the world’s oil. The leader of the pack is Saudi Aramco of Saudi Arabia. Their proven reserves could keep the world supplied with oil for decades. Currently they only exploit 10 out of their 80 fields and at the present rate could continue pumping for another 70 years without ever having to discover another drop.

Some of the other significant NOC’s include National Iranian Oil Company (Iran), Gazprom (Russia), INOC (Iraq), Qatar Petroleum (Qatar), PDVSA ( Venezuela), Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (Kuwait), ADNOC (United Arab Emirates), Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (Nigeria), Sonatrach (Algeria), Libya NOC (Libya), Rosneft (Russia), Petronas (Malaysia), Statoil (Norway), Petrobras (Brazil), Pemex (Mexico), YPFB (Bolivia), Pertomina (Indonesia), Oil India Limited (India), China National Petroleum Corp., China Petrochemical Corp., China National Offshore Oil Corp., and Shaanxi Yanchang Petroleum Group Co. (all 4 are in China).

But, if the amount of oil at state companies’ disposal is not much of a worry, the way they manage it certainly is. States and politics tend to meddle in the business affairs of their NOC. At best these are characterized by inefficiencies, overstaffing, underinvestment and so on. At worst, the business of producing and selling oil is entirely submerged in politics and creates less oil being produced more expensively. Some of the solutions would be to privatize them (not likely), or subject them to competition by allowing foreign firms some access to their home territory or by having them expand abroad themselves, or at the very least grant NOCS operational autonomy and allow them to retain and invest some portion of their earnings.

Chavez’s handling of PDVSA since coming to power in 1999 is a good example of poor management. Chavez stopped the practice of retaining profits for reinvestment by the company and instead kept the profits for the state. He fired most of the management and replaced them with family relatives. Most recently he has instructed the company to sell less to the USA and more to Latin America. This past year saw Bolivia’s Morales nationalize his countries oil fields. More than 30 foreign oil companies stopped operating in Bolivia and investment has largely dried up. The NOC itself lacks the expertise to run most of its own oil fields and has very quickly moved into economic retreat.

Some are better than others. Norway’s Statoil is generally considered to be the best of the lot. The principles of a democratic country have ensured that fundamental business practices exist. Also countries such as Brazil and Malaysia have encouraged their NOC’s by allowing foreign companies to compete for the right to produce their oil fields. Not only does the competition ensure the NOC keeps its cost down and methods up-to-date but it also creates a pool of skilled labour in the country. As well these NOC’s are encouraged to work in other countries also.

Few oil rich countries have avoided the triple threats of corruption, competitive rent-seeking or “Dutch Disease” in which thanks to exchange-rate appreciation, oil production crowds out other economic activity. Norway’s model, which has built a huge stabilization fund without distorting its economy, is the goal of others. However it is miraculous if a poor country, under intense social pressure, can ever achieve such a feat. The risk for countries such as Azerbaijan, Venezuela, or Nigeria is that the oil bonanza will end up hurting the people it ought to help.

From the Thursday Files:

Cosmic upheaval is not so moving as a little child pondering the death of a sparrow in the corner of a barn.

– Tom Savage

Share This Column