Dedicated to all those who work on a seismic crew, and the ones who love these people.

When I started to study Geology at the University of Calgary I never realized that my career would take me to some of the more interesting points in the world. I remember sitting in my Sedimentary class wondering why I was studying the Mississippi Delta or why we were learning about Pingos in Geomorphology when I would never see one. My career has seen me take on many challenges, deal with many situations, and has taught me to accept challenges as they come along. One of the things I have learned above all else is never say that you won’t do something or you will never see something. I have seen everything from Buckingham Palace to Mayan ruins. My journeys have taken me to many different places and have taught me to learn to seize the moment.

Doodlebuggers have an interesting history. At one time they were farmers who wanted to earn extra dollars in the winter time. Juggies may not be as educated as we are, they tend to go from one job to the next earning sometimes as low as minimum wage, but they are vital for our industry. We joke about the people on the field crew, treat them as if they are below us, but it is the job they take on which allows us to do our work in the processing centers, in the oil and gas companies. Their work even affects the stock market.

The people who work offshore or on the land crews pay costs each and every day for the job they do for us. Personal costs like time away from family, working abroad, having to endure hardship, and tough working conditions. They wake up to the same people for 6 weeks or 36 days. These people become your family; you depend upon each one of them to do their job correctly in order for you to do yours.

The following is a reflection of the time I spent in field processing to give those who interpret seismic data in the office an appreciation for those who work in the field. My first time on crew was in the winter of 1992 when I worked on a Geco-Prakla crew on the North Slope of Alaska. I had many adventures on this crew. Each morning we moved camp and these camp moves were very exciting.

I had the opportunity to drive one of the vehicles during a move. As I was driving the engine died and I was stranded. I got on the radio and said that my engine was dead. The mechanic immediately asked me where I was. It is hard to describe how barren the North Slope is until you need to find some sort of landmark to go by. There are almost no landmarks to get your bearings by so I said, “I’m behind the Recorder in front of the next vehicle.” When the next vehicle pulled up alongside the mechanic asked him where I was and his response was, “I’m beside the stalled vehicle behind the Recorder.” Frustration was heard on the other end of the radio and laughter. Without GPS it was easy to get lost on the North Slope, especially in a white out.

It was on the North Slope that I saw my first Pingo; a hill formed in the tundra due to ice uplifting because of buoyancy, if anyone asks you in a game of Trivial Pursuit. Caribous usually grazed around the Pingos, the center of which is a block of ice. Pingos were the only relief on the North Slope of Alaska.

One time in a white out we were in the Recorder and we weren’t too sure if we would go back to camp that night because we did not have GPS. The Party Chief came out to get us and while we were in a convoy back to camp we got lost. The vehicle was only 20 feet in front of us and we could not see it anymore. We then traveled about 100 feet and found the Party Chief’s bombardier again; we had traveled in a complete circle thinking we had traveled straight. While we continued into camp the generator caught fire, we had to jump out of the cab without our parkas on and put it out while the frigid air cut through to our skins.

There are people who died from exposure after being lost in a white out up on the North Slope. While we were being rescued the surveyor rolled his vehicle, accidentally going over a cliff. GPS tells you position but it does not tell you about cliffs.

After experiencing the cold of the north I was transferred to the swamps of Louisiana. The project was Geco-Prakla’s first attempt at the transition zone in the Gulf of Mexico. The project involved the testing of the marine vibrator.

The Marine Vibrator showed promise on this survey. The problem was penetration of signal into the ground. The signal was very good in the shallow section but was attenuated in the deeper section due to the fact we had only one Marine Vibrator. The issue with the Marine Vibrator was to synchronize four marine vibrators together, similar to what we do on land crews. An advantage of the Marine Vibrator is it can be used in environmentally sensitive areas.

One of the fun parts of working on the transitional zone crew was riding the airboats. At one time I had my own motor boat to go back and forth from the Recorder barge. On one particular occasion I was in a hurry to go to the Recorder barge so I did not take my PPE’s or personal protective equipment, such as a life vest or radio. I took a short cut through a restricted area where there were shallow pipelines. The engine hit a pipeline causing the top to fly off and I jumped into the water knowing that it was relatively shallow. When my feet hit the sea bottom they sank like lead weights pulling me into the water. The Mississippi river bottom is mostly mud which acts like quicksand. I pulled myself up using the edge of the boat losing my shrimper boots in the mud. I tried to restart the engine but in my struggle to avoid being pulled into the mud the engine had become wet. So there I was, stranded. The engine did not work, my boots were lost, and I had no life jacket or hard helmet on and no radio. Three hours later after sunbathing I was discovered drifting. After telling my story to the Party Chief I was reprimanded; particularly for going into the water where there could have been alligators or water moccasins.

After working in Louisiana I was transferred to a crew in McAllen, Texas. I had gone from the Milk River in Alberta to the Rio Grande in Texas. McAllen was an interesting project where we shot seismic right in the middle of town.

After McAllen I transferred to the Marine department. My first job was an infill shoot around rigs in East Cameron utilizing the Digiseis buoy system and performing static binning with the Geco-Prakla Spider system.

The way the buoys were deployed is someone would watch the GPS on the Crew Boat and when we came to a receiver X and Y on the GPS he yelled "Drop!" and the buoy was deployed from the backend of the crew boat. This was done off of the Crew Boat Sea Star. After laying out all those buoys we had to watch the lines so no shrimper picked them up at night with their nets. The airguns then went in utilizing the Marlin as the shooting and recording boat and we shot the source lines. I did the static binning to ensure we had enough fold. This produced the SPS files used for the geometry in processing.

My favorite job offshore was to go out on the MOB (Man Overboard Boat) and work on the tail buoys or the streamers. When working on the tail buoy you need to avoid going in front of them. One time we happened to drift in front of the Tail Buoy as we were trying to get on to it to fix the antenna, the tail buoy smashed into the MOB boat dragging it. Alarms within the instrument blared indicating there was a problem. The tail buoy was wound up like a spring with all the tension and was listing on its side while the MOB boat was also on its side creating a V where the apex of the V was at the junction between both. Then with a "whoop" the MOB Boat managed to get off the tail buoy and the antenna swung around hitting just above my head. The driver looked cautiously over fearing that I had been decapitated by the antenna.

There have been deaths on the vessels, and vessels have sunk. We practice safety procedures each day, but it is scary when there actually is an emergency. One of my friends was on the MOB boat when it capsized. His vest was supposed to automatically blow up but it did not. Instead of blowing air into it using the tubes he immediately panicked and tried to climb on someone whose life vest did work. This guy turned to my friend and said, “What are you trying to do?” My friend said, “My vest did not work.” The co-worker replied, “I guess you are screwed.”

We practice helicopters crashing, getting into the life boats, finding alternative routes to the muster point in case there is a fire and the primary route is blocked; we learn how to fight fires and how to do first aid. All the training we do and it comes down to 1 second of thinking instead of panicking. You don’t know how you will react until it happens. We are always taught to stop for 3 seconds, think, look around you, then do what you need to do. The 3 seconds is just to calm you down.

Another dangerous place is the backdeck when we need to pull up the equipment. Each time those streamers come in there is a lot of tension on those cables. One disastrous trip on the Geco Alpha saw us snag a floating anchor on our streamer. We could not use the MOB boat to take it off so we spent days bringing cable in very carefully inch by inch until the tail buoy with the anchor attached to it was at the gun slip. We were poised to bring it up and to finally remove the anchor from the tail buoy. As we pulled the buoy up the gun slip the anchor broke away. The whole moment was very anticlimactic.

There are from 4 kilometres to 8 kilometres of cable. Along the cable are birds which keep it at the right depth, compasses which help navigation calculate coordinates, pods which receive sonar pulses, GPS units on the tail buoys, and a laser on the back of the boat shooting a beam to a target on the center of the gun array. All of this is needed to create a net of information to determine offsets at the front and rear of the streamer. We use the compasses to determine the shape of the streamer in the middle. All of this equipment is somehow attached to the streamer and needs to be taken off as we bring it in. If a cable snaps there could be such tremendous force it would cut through metal.

One of a sailor’s biggest fears offshore is fire. We practice fire fighting quite a bit but you really don’t know what will happen until it really happens. We practice just so we understand what is expected from us and what our roles are during a fire. One time at 4:00 am the alarms went off and I stumbled out of bed. I grabbed my coveralls and threw them on. All the fire doors had shut and there was massive confusion of people getting up to the muster point since they had never done it before half asleep and with the fire doors closed. It had turned out that someone had done some hot work near a smoke detector without informing the bridge and getting a hot work permit.

If fire occurs then it is up to the crew to fight it. We learn how to work the hoses because one of our assignments may be to spread water on the deck above the fire to cool it down and contain the fire.

One of the funniest stories I heard is when the Geco Apollo was sinking, the Indian crew had gone to their cabins to get the merchandise they had bought while working in the States to load onto the lifeboats. When the Apollo sank in the Gulf of Mexico people just walked off the vessel. The sinking had occurred during refueling at sea and the ship had lost ballast and was listing to the side.

One of my friends said most left with their orange coveralls only. In the state of Texas convicts wear orange so we know who they are. The story goes that the agent took the crew to a Wal-Mart to buy clothes so they could travel home. Some of the folks in the store became worried seeing burly men in orange jumpsuits and there were a lot of questions.

As Chief of Onboard Processing (OBP) I was in charge of the Field Processing people. Each department has a Chief and a shift leader who acts as a Chief when the Chief is asleep or away. We all then report to the Party Chief. The Captain on the vessel is in charge of the vessel and maritime crew and the Party Chief is in charge of seismic operations and the seismic crew.

I had to deal with some strange personnel issues ranging from someone quitting because this wasn’t what they wanted to do, to counseling someone about their career choice, to actually having someone with tuberculosis, and having this person sent to Manila for testing. When it came back positive the vessel was quarantined under Norwegian Law since it was a Norwegian flagged vessel. A quarantined ship needs to raise a black flag indicating it is quarantined but still, all the merchants from Batangas came out in their small boats to sell us beer, cigarettes, and souvenirs.

One of the great perks of working offshore is the travel you do and the adventures you have while traveling. I remember spending some time in Sanya, China. There was a bar owner who wanted me to buy him custom designed boots in Houston. The boots he wanted were very outrageous. He would pay me when I returned to Sanya. While there, he allowed me to drink for free while he was in the bar. I also remember meeting many people and learning their customs and languages.

I actually met my wife while working offshore. Pyrigo, one of the people on my crew from Indonesia knew my future wife and introduced us. It was difficult at first getting used to different customs, and accepting how others lived. I once spent a day trying to find toilet paper in my in-laws house instead of noticing the little bucket that sat next to a big container of water.

Shortly after getting married, I went to work off of Indonesia. The forest fires were raging and there was always a smoky haze. My wife was awoken one morning at 5 am by her father who told her two ships had just collided near where I was in the Malacca Straits between Indonesia and Singapore. My wife spent the day waiting for the names of the ships, while I was oblivious to what was happening in the world around me. When I phoned that night she was extremely relieved.

The day of crew change we went into Medan and boarded the 10:00 am flight to Singapore. I was traveling all day and expected in KL late in the evening via Singapore. The flight out of Medan to Jakarta at 2:00 pm that afternoon crashed into the mountainside. My wife was very anxious because she did not know my travel plans. When I phoned her from the Singapore Airport late that afternoon, after spending some time shopping for a stuffed toy for my daughter, she was very relieved, knowing only then I wasn’t on that flight to Jakarta.

I returned once again to the vessel. While offshore of Indonesia I received word my pregnant wife was in the hospital in Las Vegas, having collapsed in her Grandmother’s house. I was awoken by the First Mate saying that there was an emergency at home. I ran up to the bridge, and after trying several times, I finally managed to get my wife’s Aunt on the satellite phone asking her about my wife’s condition, and trying to decide what to do because it was a 2 day journey back to the States. My wife’s Aunt assured me all was being taken care of and for me to stay. A word of warning to most men, in a situation like this please go home because in a fight 10 years later your wife will bring this up. I did send my wife a Pooh bear over the internet to say I love you, and get well; and every Christmas we put that Pooh bear out as a Christmas decoration.

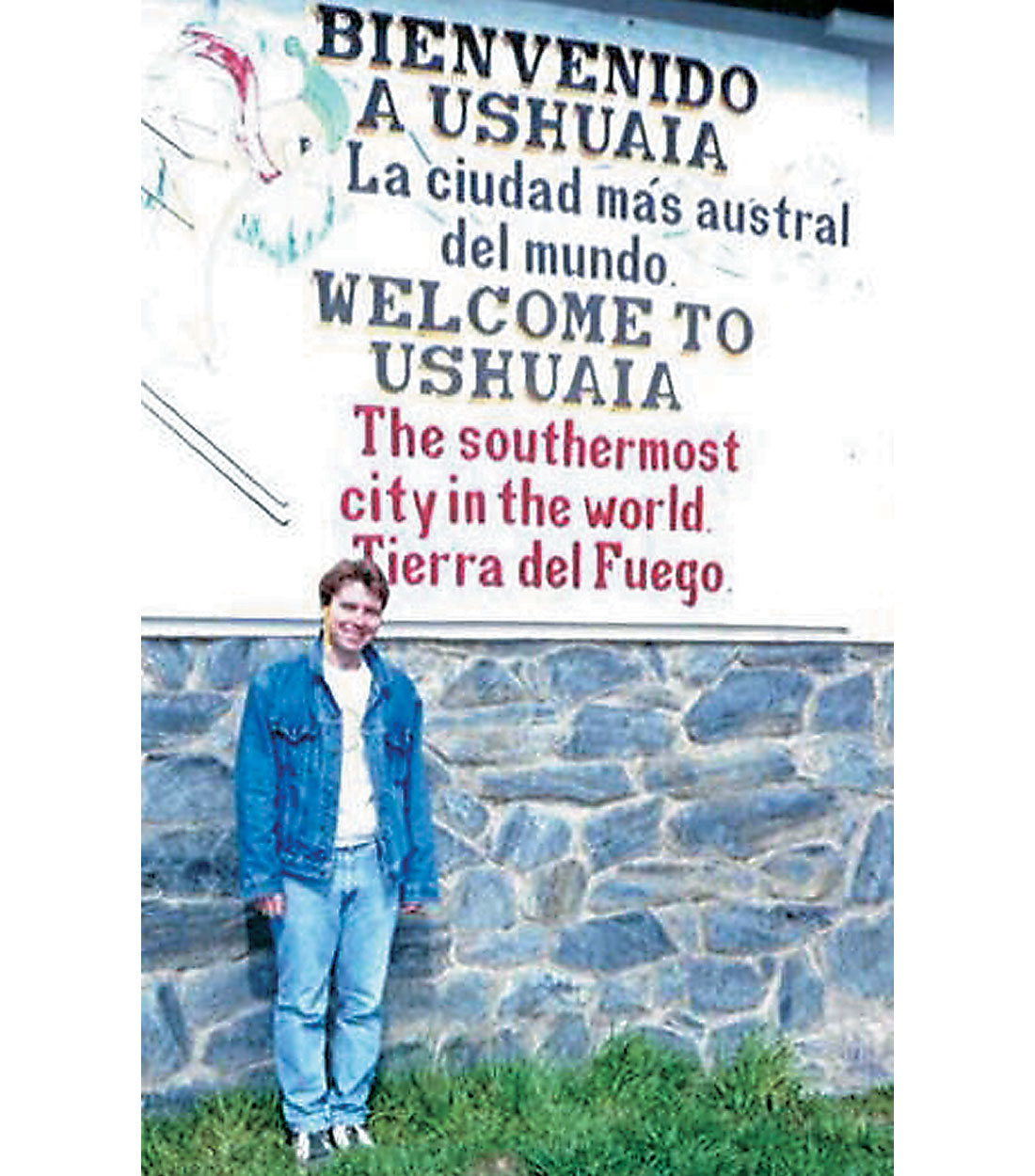

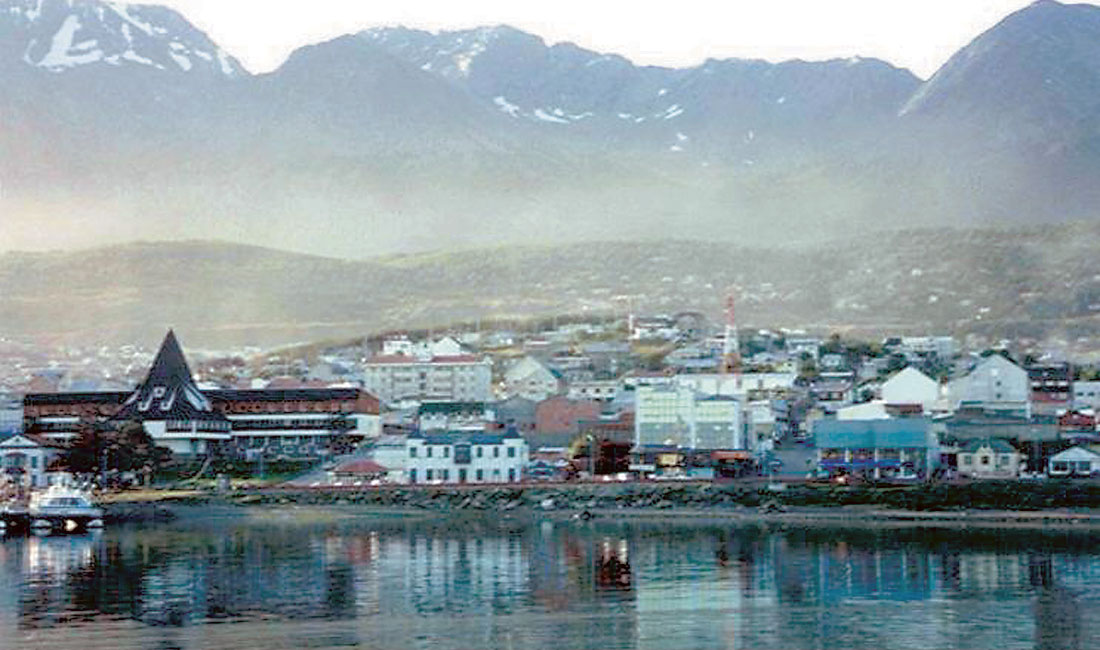

My travels have taken me to such places as Mexico, Argentina, China, Indonesia, Australia, Holland, England, Malaysia, Thailand, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. I have been very blessed to be allowed to be a part of seismic acquisition, to have seen the wonderful things I have seen, and to have been able to meet the wonderful people I have.

When talking about Juggies and people who work in the field have respect for them. You have no idea the type of life they may have led. Realize education comes not from a school of higher learning but from experience. I have met people who are highly intelligent and prefer an alternative life style. Hold your judgment upon someone. Also with all of the free time on a boat and all the waiting we must do, we usually have read quite a bit, dabbled in electronics or with programming and have watched our fair share of videos; even to the point we can actually speak the lines in the movie.

Our industry maintains a diversity of people who may or may not be educated. We need to learn to walk with Kings and still keep the common touch in order to successfully manage all the disciplines, and individuals within our industry. The biggest downfall for some when they went out to the crew is they believed they were above everyone else. Field work is used by companies to teach you how to manage people of different backgrounds; working internationally we have different cultures to deal with as well. We need to walk a fine line between being able to understand the issues involved in a country without becoming involved.

Whenever you look at a seismic section have a look at the acquisition parameters and realize how many people were involved beyond yourselves in the creation of that wiggle so we can find oil and gas. Appreciate the dedication and hard work that was put into that seismic section from the second the guns went pop to when you view it on the work station.

Acknowledgements

I need to acknowledge teachers and people I have worked with such as: Mr. Mooney my principal at St. Cecilia’s in Calgary, my instructors at U of C, Paul Tickle, Stefan Church, Sook Yeen Wong, Beng Lee Ang, Jan van der Mortal, Greg Abarr, Steve Svatak, the folks at Vastar, Craig Cooper, John Kaldy, Chuck Barousse, and most of all my family.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article