Shale gas is nothing new to North America. The first known shale producing well was in New York State in 1820. Although, if you look at conferences, journal articles, and contractor offerings; it might appear to be a new and exciting area of oil and gas business. The change occurred in 1998 when Mitchell Energy demonstrated a fracture stimulation technique for economically completing the upper Barnett Shale interval. This increased their core area reserves by 25 percent and kicking off the new era of shale gas production that today contributes over 22% of North Americas’ gas supply.

It is known that the major risk in most shale reservoirs is not the finding of hydrocarbons but the economic viability of the production because of the unknown permeability, natural fractures, total organic carbon or brittleness. The major advantages of shale reservoirs are moderate exploration cost, evolving technology commitment, low long term decline rates, and high success rates.

Since 1998, I have been involved with companies who were at the forefront of shale gas development, and myself working with the evolving field of shale gas geophysics/geoscience; or how to apply geoscience in an emerging engineering world.

I thought this chapter of my life was closing when Talisman Energy offered me a position in Stavanger, Norway; a place I had left 12 years earlier, Boy was I in for a surprise!!! The thought being:

- Norway is the third largest oil exporting country in the world behind Saudi Arabia and Russia, producing all of it from offshore platforms and from predominately clastic reservoirs.

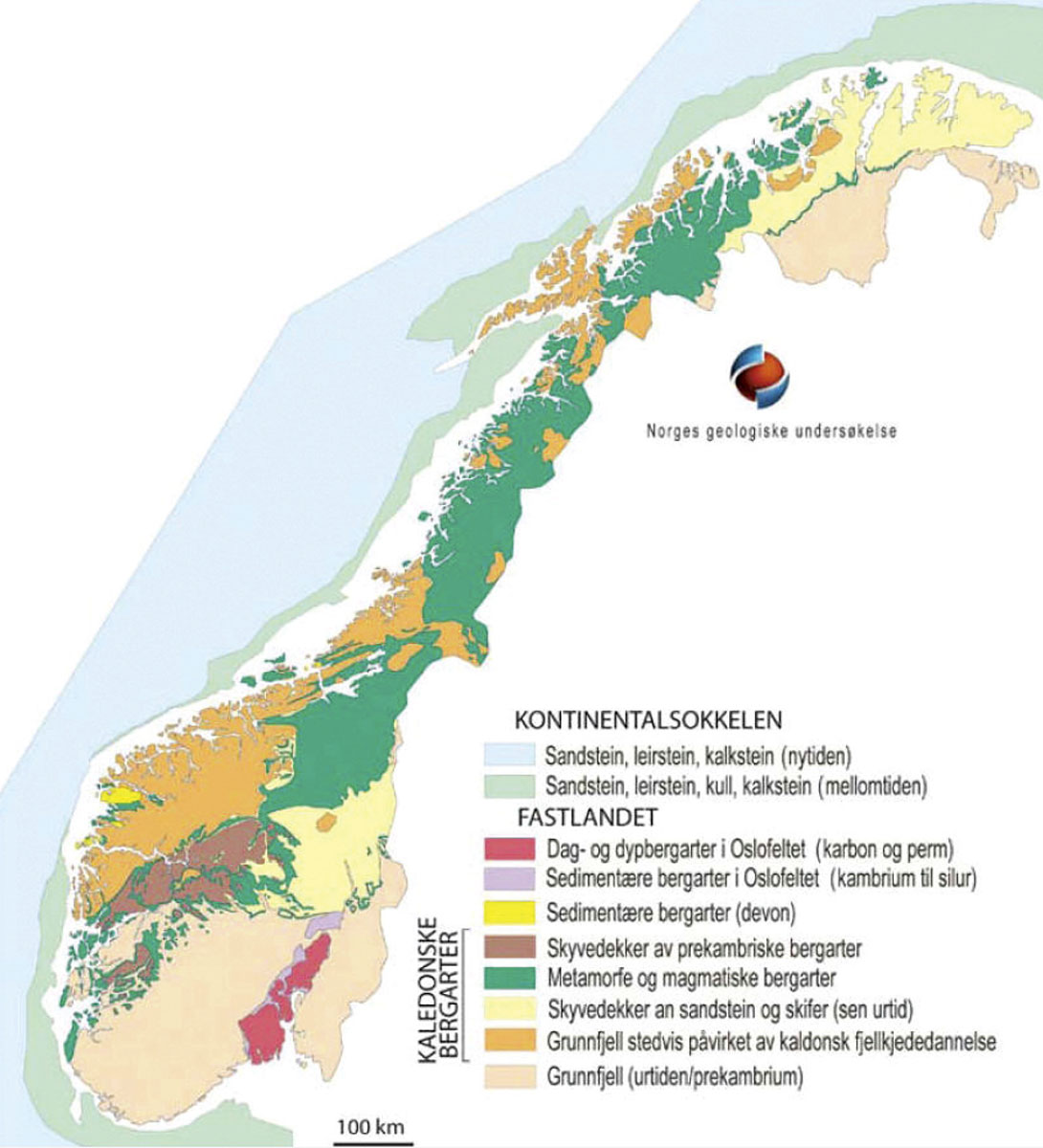

- The entire geology of Norway is made up of igneous or metamorphic rocks (Figure 1.)

Soon after arriving in Norway, Talisman Norge requested that I and Basim Faraj from Calgary make a shale gas/tutorial presentation at an investor meeting that was sponsored by the Government of Canada and hosted and opened by the Canadian Ambassador to Norway, John Hannaford. The presentation was in Oslo and proceeded by dinner at the ambassador’s residence. There were a lot of questions and heavy discussion about shale reservoirs and unconventional resources, their positive/negative points and theirre impact on Canada.

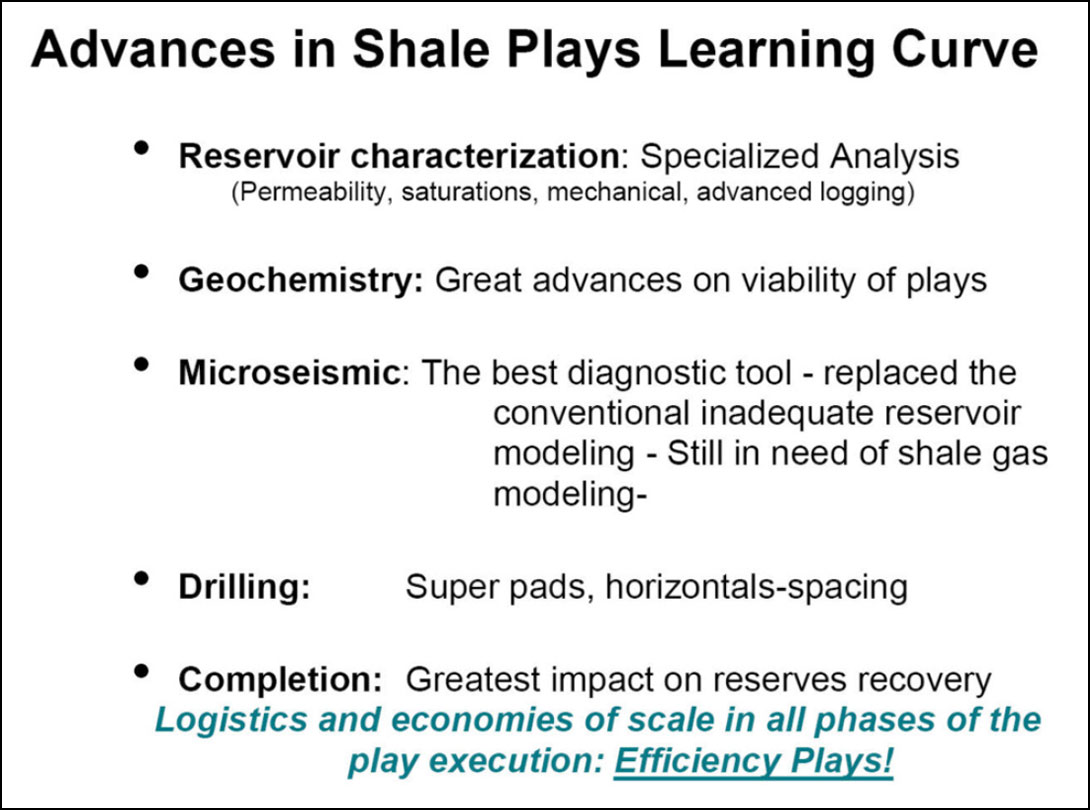

The presentations Basim and I gave started out as a typical North American shale gas talk, showing its growth, the concepts of desorbed gas and how horizontal drilling and fracing changed the game. The talks go on to highlight how 3D seismic, microseismic and 4D seismic can be used to mitigate risks and improve efficiencies in shale gas plays. We soon realized that the audiences were at a different level of understanding, the concept of horizontal drilling was common place, but fracing was a totally foreign concept. Fracing had to be explained and described in great detail, as well as the well spacing, frac spacing and shear size of the operations and developments. Microseismic was the other concept that had to be explained and demonstrated in Figure 2. This figure shows a usual outline of the talks and some of the topics discussed. The presentations went off without a hitch and were picked-up by a Norwegian technical magazine, Teknisk Ukeblad with full page photos of the technology and it future in North America.

Up to this point, Shale gas was still something new, just happening in North America, and most of the interest was from an investors point of view, and not that interesting to the Norwegian general or technical population. That was until the Shtokman story hit the newspapers. In Feb. 2010, Statoil announced that it would not be going ahead with the Shtokman development in the Barents Sea. The reason for the projects termination was the softening of the LNG market in North America, caused directly by shale gas growth. Shtokman is a gas field in the Barents Sea that is thought to be the largest offshore gas field in the world with reserves over 100 TCF gas and 200+ MMBBLs condensate. Statoil is the largest tax payer in Norway at just over 18 Billion dollars per year (or about $4000 per Norwegian citizen), one of the top 5 employers in the country, and when Statoil makes less money the Norwegian government and eventually the egalitarian/Socialist society suffers. Statoil had spent 18 years building a relationship and agreements with Russia’s Gazprom, only to now postpone and delay the development because of shale gas. This story was front page news in Norway and everyone wanted to know what this new competition to Norway was.

The first follow up to this was an interview and tutorial for the Stavanger Aftenbladen daily newspaper. A two page story ran on shale gas, what it was about, why it was new, and where it was. It did seem strange for a daily newspaper to be so interested in this and especially at this level of detail. Surprisingly and almost shockingly, after the story ran, I had a taxi driver asking me, “what really is this stuff that is going to put Statoil out of business and destroy Norway”? The requests didn’t end there, there were to follow several more presentations to the Norwegian petroleum Directorate, university classes, professional organizations and several internal presentations.

The politics really got heavy when I was requested to present at the Norwegian Storting, or parliament, to a group of the oil and gas ministers and committees. The presentation took place followed immediately by a general parliament meeting that started to debate the use and building of natural gas electric plants in Norway. They argued the new plants would use their inherent local gas supply. They based their discussions and conclusions on data from the presentation, some very preliminary market projections, conjectures, and the possibility of Norwegian gas having little value elsewhere in the world because of the rapid growth of shale gas in North American and soon to be Europe.

Now the European shale gas presentations were occurring almost monthly with invitations being offered all over Europe. The talks were being shared by Basim Faraj and myself, with Basim presenting in Oslo and a European wide Shale gas conference in Berlin, Germany. Shale was becoming very topical and everyone wanted (and still wants) to know about it. The talks were also broadening in scope with lots of interest toward the environmental factors and especially water use and possible abuse.

The government of Canada was loving all of this, I was invited again to speak at the Offshore North Sea Conference, a convention with over 40000 attendee, by the Canadian ambassador to Norway, The Ambassador presented that Canada, like Norway is an oil exporting country, is CO2 positive in energy consumption by producing 85% of their electricity from hydroelectric and is the primary contributor to a much larger consumer nearby. This presentation highlighted Canada’s commitment to natural resources, their support of unconventional reservoirs, and these reservoirs contribution to Canada’s economic and political benefit.

The Storting was an unusual request, followed by an ambassador’s invite to a European technical session, until the Barcelona invitation showed up. Here was an invite from the Norwegian association of Oil and gas lawyers. They requested that I fly to Barcelona to present shale gas in English. I was requested to make the talk very non-technical, but informative and directed at a non-geoscience community. I made sure I used small words. The culmination of all of the shale gas talks that Basim Faraj and I have given was here I was in a Spanish hotel speaking to 150 Norwegian lawyers about shale gas.

A new geographical area was coming on the scene throughout 2010 and that was Poland. Poland has had a large land grab and most shale gas players from North America have been involved. These new natural gas and economic opportunity are very exciting to these countries and there local geoscientists, but this was also stirring another European giant exporter called GAZPROM, the Russian oil company. They stand in the very same position as Norway and Statoil, with over 22 billion dollars paid in taxes, sales of gas to 22 European countries and 500,000 employees. The future of shale gas in mainland Europe could become a threat to their exports and tax payments to Russia. Politics are heating up in the European community directed at shale gas development and regulations, and these issues are far from being resolved.

Conclusion

Geoscientists tend to concentrate on technical issues, trying to generate new ideas and concepts, and reducing the risk of finding hydrocarbons. We usually ignore or avoid the politics of what we do and how it affects other people in other countries. The interest that has been shown in understanding and learning about shale gas from European politicians, national oil companies, oil ministers, and new ventures managers demonstrates what shale gas could do for the economies and resource control in Europe. This same argument could be made for the world as a whole. Shale gas has changed the balance of power for many countries including the United States and Canada. With the United States now exporting LNG to Europe and with several countries exploring for it, this shows that the balance shift will continue. This can only keep the Canadian geoscientists, who reacted to the new resource with new technology and adaption of methodology to the new unconventional resource, in the forefront of expertise and knowledge. It also shows that natural gas has now become a large resource that will change how we live and work. This is in addition to changing the economic balance throughout the world.

The demand for knowledge on shale gas reservoirs is ongoing; The European Union parliament has requested an introductory and explanatory shale gas presentation, along with other regulatory branches of European countries for the coming year. So the tour will continue, so much so, were thinking of making tour T-Shirts.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article