A survey was issued by the Canadian Society of Exploration Geophysicists (CSEG) to gauge the public’s perception of induced seismicity (IS) in the summer of 2014. It revealed that education efforts on IS should be collaborative involving industry, academia and regulators, but documents issuing from this work must crucially be seen to be non-partisan. Of the sixteen operators that monitored for IS, only five had monitoring protocols in place, suggesting there is considerable room for improvement through education, direction and collaboration. An earlier survey conducted at the Induced Seismicity Forum (ISF) held on November 22, 2013 was integrated into this report. The objective of that forum was information sharing to establish a common technical basis and identify a vision for environmentally sound operational practices for injection projects. It had representation from government agencies, regulatory bodies, industry organizations and utility, operating and service companies. Comments stated that more work should be done by the industry to improve monitoring solutions, establish protocols for and mitigate the effects of IS. Most respondents were satisfied with the participation, but said that next time participation should be broadened to include the public and local/ regional stakeholders. The subsurface order made by the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) on February 19, 2015 regarding the monitoring and reporting of IS in the Fox Creek area of Alberta was a step forward to improve and establish protocols and best practices for monitoring seismic events in energy producing fields. The purpose of both surveys was to determine the understanding and awareness of seismicity related to hydraulic fracturing, identify educational efforts and areas of improvement for operational protocols.

Introduction

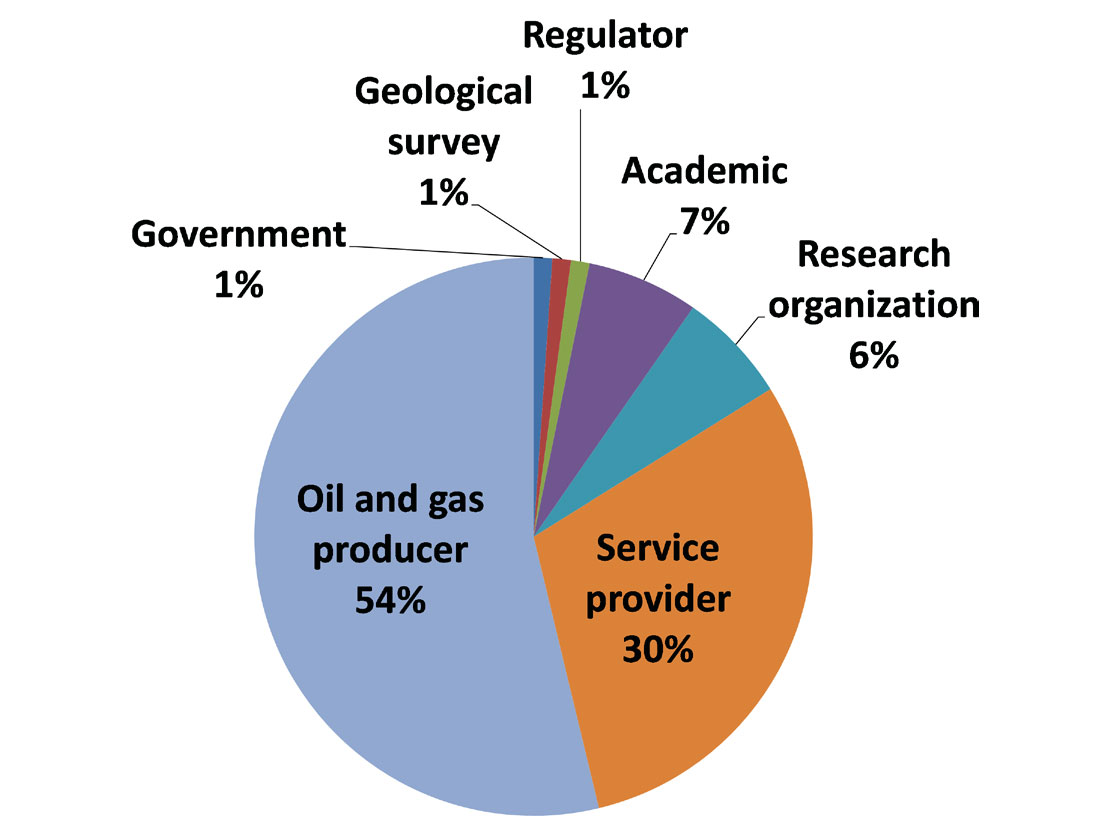

The Microseismic Subcommittee (MSSC) of the Chief Geophysicists’ Forum (CGF) under the CSEG prepared and analysed two surveys on the topic of IS. The newer survey, on the public’s perception, was conducted in August 2014 and issued to only CSEG members. The older survey followed the ISF held in November 2013 and was issued to the attendees representing a variety of organizations (Figure 1). It gauged their response to IS. Results from both surveys are combined in this report.

Established in 1949, the CSEG hosts about 1,800 members. Geophysicists actively involved in hydrocarbon exploration and production make up approximately 60% of the membership. Individuals from academia, geologists, technical and field specialists, other interested members of the public, industry and retired personnel make up the remaining 40% of its membership (CSEG, n.d).

Both surveys were designed to measure understanding and awareness of seismicity related to hydraulic fracturing. The August 2014 survey focused on four areas:

- Definition of induced seismicity

- Operating protocols for oil and gas companies

- Public and environmental safety

- Education efforts

For each point overall awareness, concern and perception were assessed. The results of the survey determined the educational efforts required to bring awareness and understanding to IS, identified areas of improvement for operational protocols and established constructive dialogue between the industry and public.

Method

The August 2014 survey was administered electronically to all CSEG members across Canada. Fourteen (14) questions were asked and forty six (46) people responded. The November 2013 survey was also administered electronically, but only to the audience members at the ISF. Seven (7) questions were asked and thirty two (32) people responded. Each question required a response before proceeding to the next one.

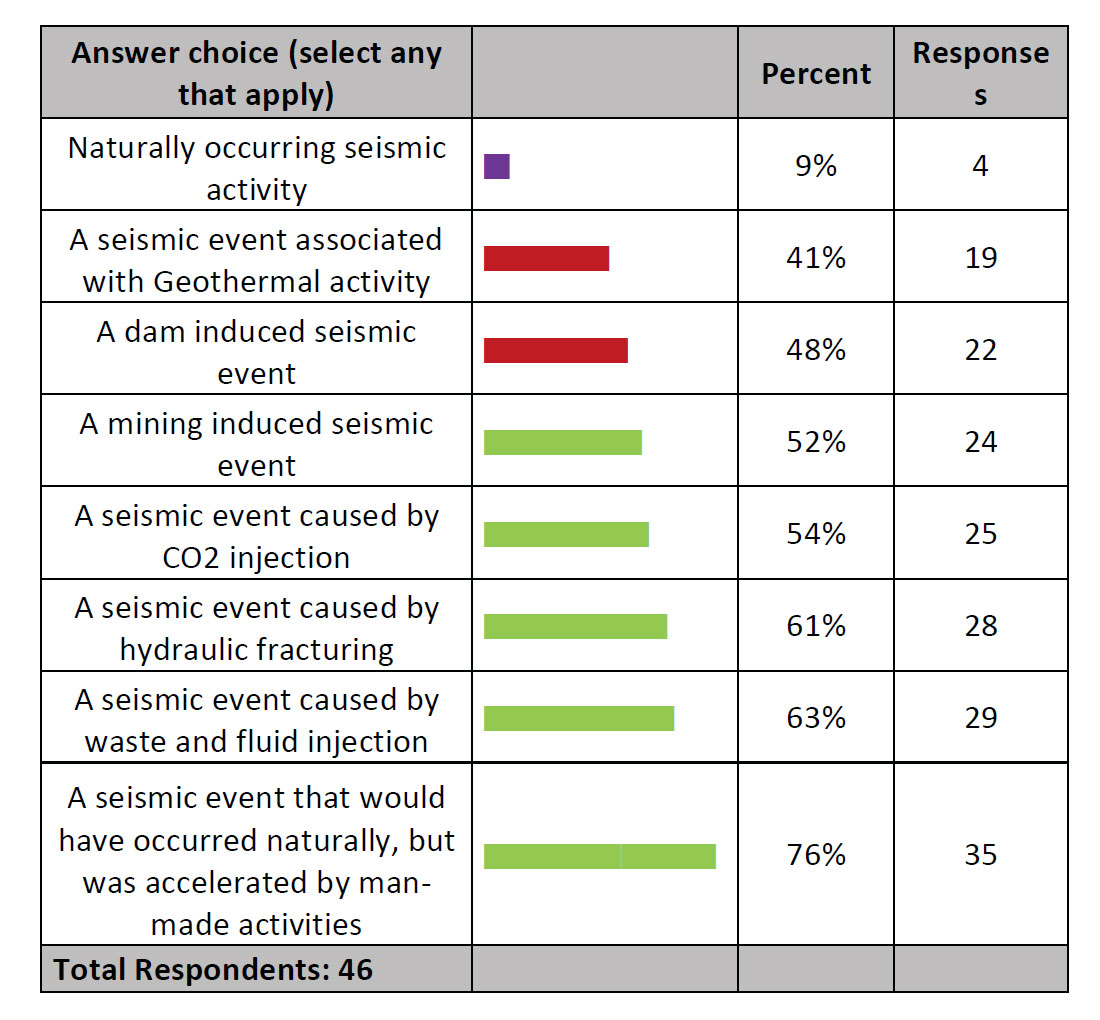

The term “induced seismicity” is defined here as an event generated due to man-made activity versus “triggered seismicity” defined as an event that would have occurred naturally, but timing was accelerated due to man-made activity.

Definition of Induced Seismicity

CSEG members were asked to describe the term IS based on a list of definitions and to select any that apply (Table 1). A seismic event that would have occurred naturally, but was accelerated by man-made activities topped the list getting over three quarters (76%) of the responses. Naturally occurring seismic activity was selected the least (9%). Between 41-63% of individuals considered it to be any of the following: a seismic event caused by waste and fluid injection (63%), hydraulic fracturing (61%), CO2 injection (54%), mining (52%), dam (48%) and geothermal (41%) related activity.

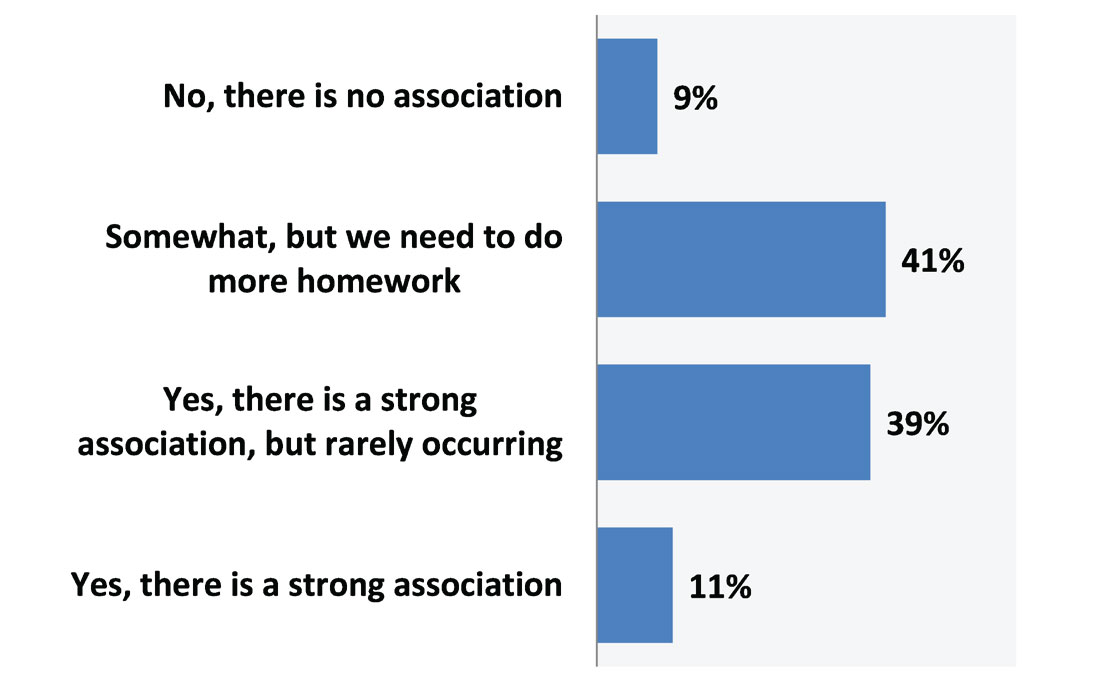

Since these surveys were targeted at getting feedback on seismicity related to hydraulic fracturing, the next questions asked if we can confidently associate IS to hydraulic fracturing (Figure 2). The majority of the responses (41%) said “somewhat, but we need to do more homework”, closely followed by 39% who said “yes, there is a strong correlation, but rarely occurring”. Fewer people said “yes, there is a strong association” (11%) and “no, there is no association” (9%).

Operating protocols

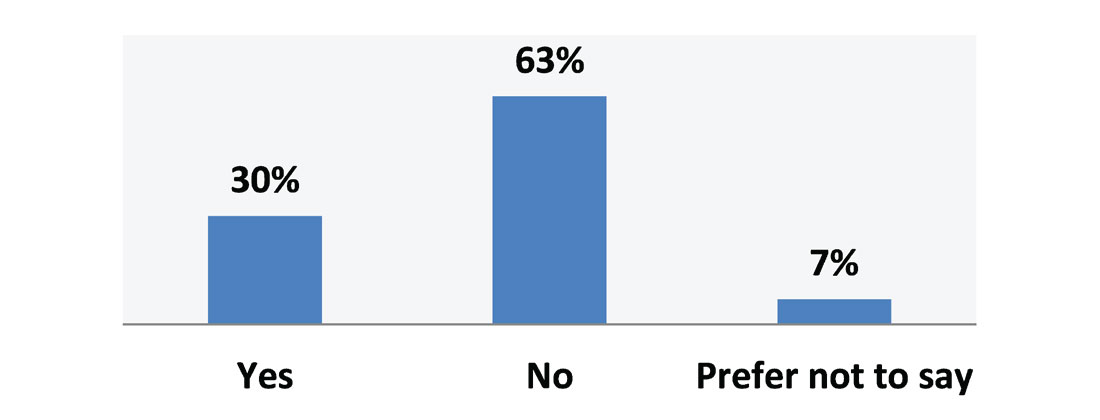

In order to understand an operator’s experience with IS, statistics on whether or not the company or organization considered an event to be induced from monitoring hydraulic fracture activity were compared. Figure 3 shows that 63% said “no”, 30.43% said “yes” and only 6.52% preferred not to say if they experienced a seismic event considered to be induced during microseismic monitoring of a hydraulic fracture program.

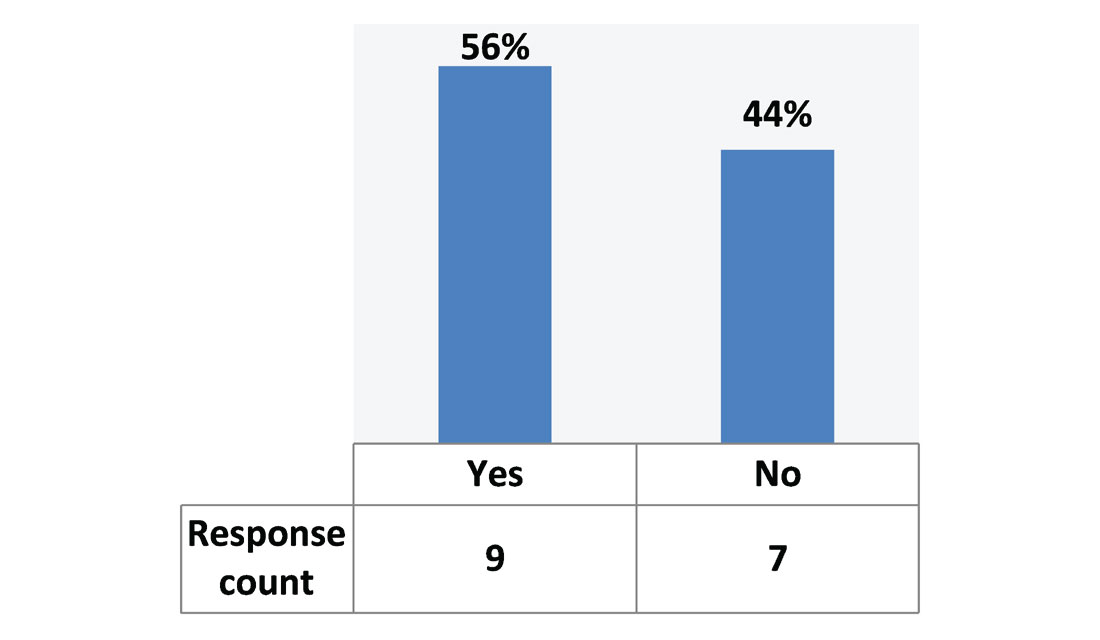

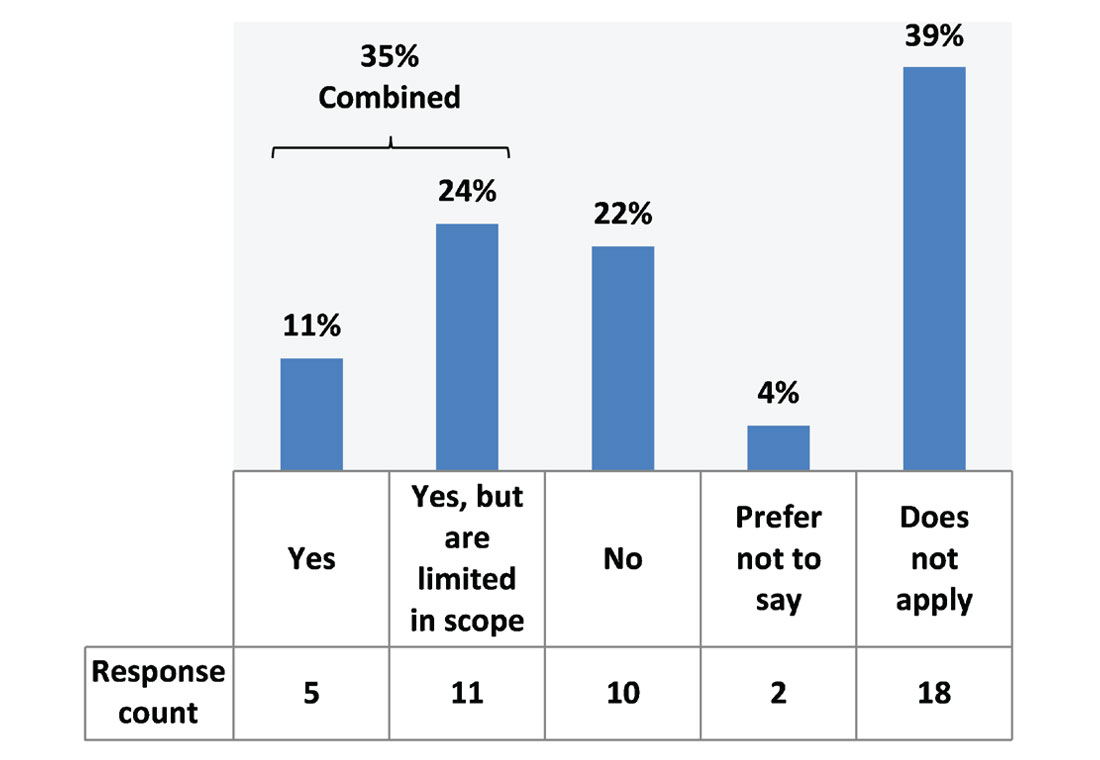

Responses from both surveys were compared on whether organizations have operational protocols in place. More options were provided to the respondent in the August 2014 survey, so the November 2013 statistics were filtered to analyze the Oil and Gas producer responses. In the November 2013 survey, when asked if there are existing protocols in place, 56% (7) said “yes” and 44% (9) of the Oil and Gas producers responded “no” (Figure 4). The yes to no ratio (YNR) of response count was 1.29. However, in the survey conducted August 2014 some improvement in the operational protocols were noted. Figure 5 showed that 35%, a combination of “yes” and “yes, but limited in scope”, of respondents said their organization had monitoring protocols in place while 22% still did not. Almost a quarter (24%) of respondents had protocols that were limited in scope. The YNR of response count, using the combined “yes’s” was 1.60. The increase in YNR hints that progress was made in improving operational protocols. There were some organizations, from the August 2014 survey, for which this question did not apply (39%) and 4% selected “prefer not to say”.

Public and environmental safety

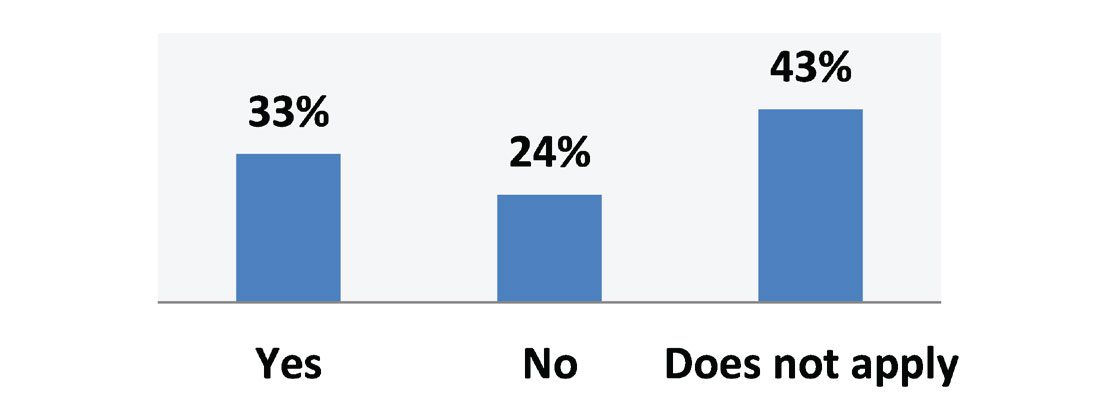

For context, the study first evaluated the impact and concern IS had on company operational protocols. Figure 6 shows that 33% of respondents said that “yes” IS posed a concern to their company’s completion program, schedules and planning. One comment said that it had caused their company to set up monitoring systems and report events above a certain magnitude, whilst another said that it now complies with CAPP guidelines and thinks about “Assess, Monitor, Mitigate and Respond” (CAPP, 2012). Another company has stated that it was proactive in evaluating Health, Safety and Environment (HSE), public relations, and immediate and long term economic impact. Those who said “no” made up 24% of the respondents and 43% said that in does not apply to their organization.

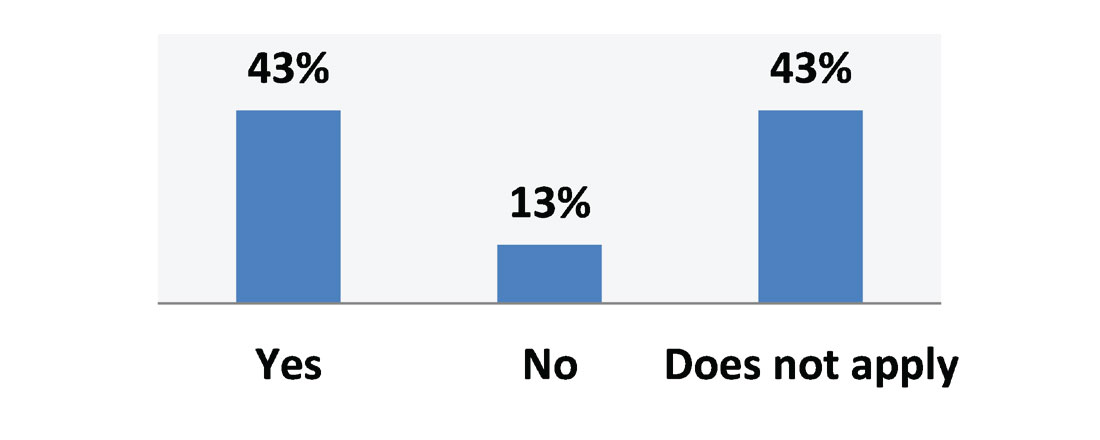

Similarly, the next question asked if the company is concerned about the impact IS has on operation, completion programs and scheduling. Figure 7 shows that 43% said “yes”, 13% “no” and 43% said “does not apply”. One respondent added that operating and completing wells is an expensive process, so the more time it takes the more money is required.

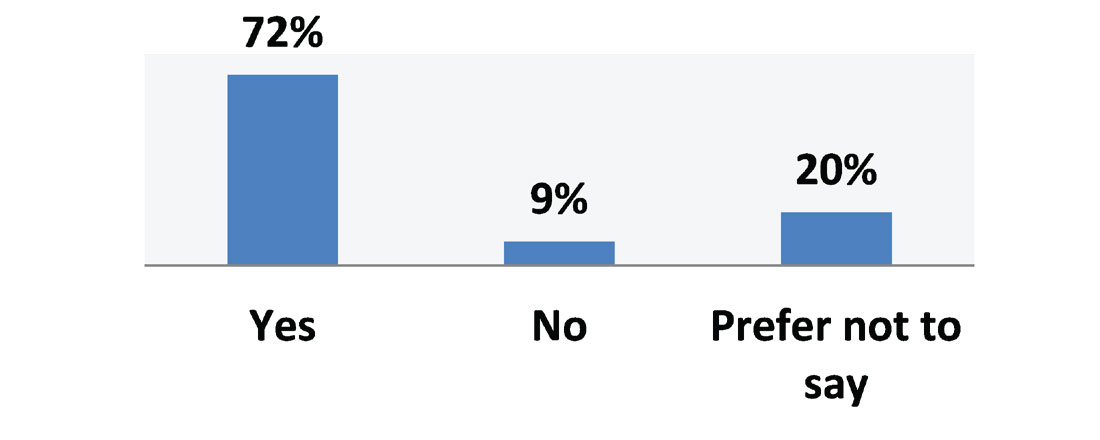

Most companies/organizations are concerned about the impact induced seismicity has on the public. Figure 8 illustrates that 72% of companies are concerned about the impact IS has on the public, while only 9% said “no” they are not concerned. The other 20% said that they “prefer not to say”. A filter was applied and showed that 75% of those who are concerned about the impact IS has on their organization’s operations are also concerned about the impact it has on the public. This suggests that even though these individuals have a responsibility to their organization, they also have a responsibility to the public.

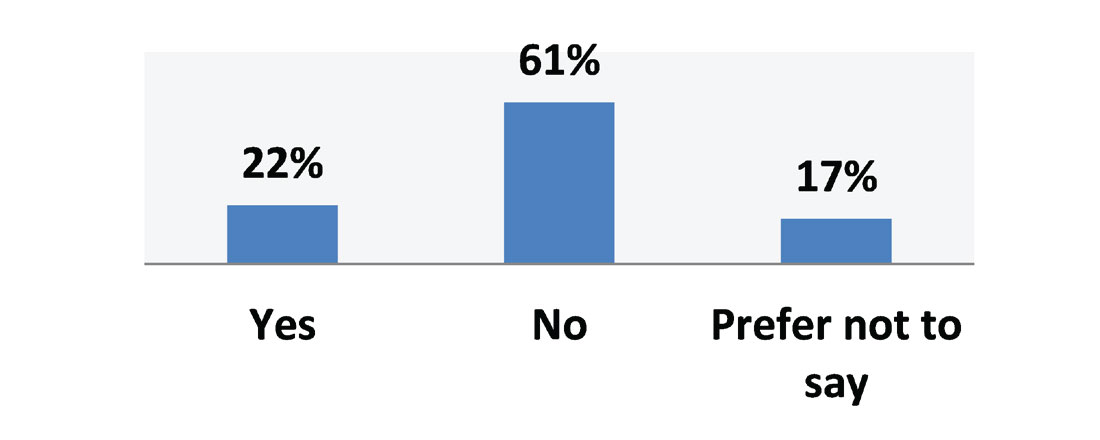

When asked if they had to take action in defense of their company/ organizations’ hydraulic fracturing activities (Figure 9), nearly one third (22% of the total sample) said “yes”, 61% said “no” and 17% preferred not to say. Of the organizations that have had to defend their activities, 80% already monitor for potential IS. This means that organizations with hydraulic fracturing operations had already identified areas with potential seismic risk, and were simply being proactive and/or just collecting baseline data in order to build their knowledge.

Education efforts

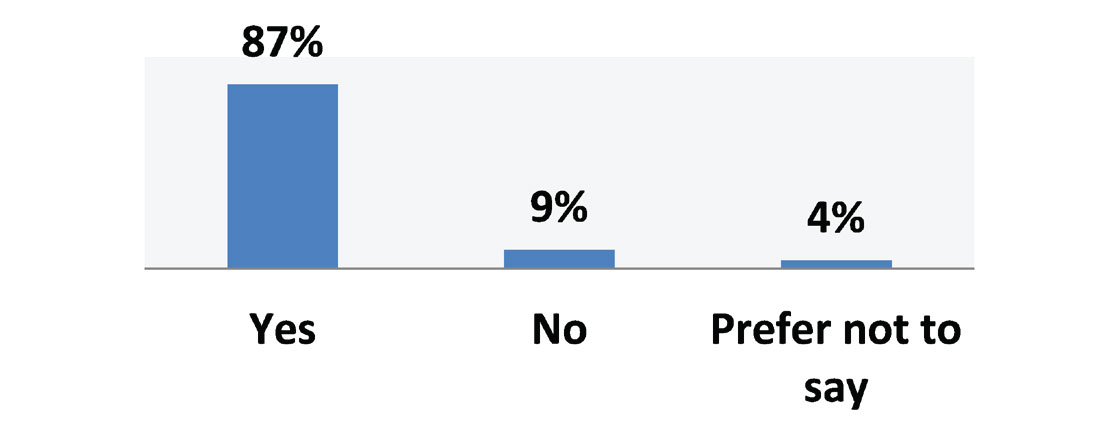

Public debate has a potentially damaging impact on energy extraction from unconventional resource plays. The August 2014 survey was design to understand public perception of induced seismicity. Therefore, understanding IS from a technical perspective, educating the public on IS, establishing and implementing operational protocols for oil and gas producing companies is a priority. The August 2014 survey first asked if IS has received negative attention in the media, to which 87% said “yes” and 13% said “no”. Then, it asked if the negative perception can be reduced to which 87% of the total sample replied “yes”, 9% said “no” and 4% preferred not to say (Figure 10). This shows that despite the negative attention IS has received in the media; it can be reduced with some effort.

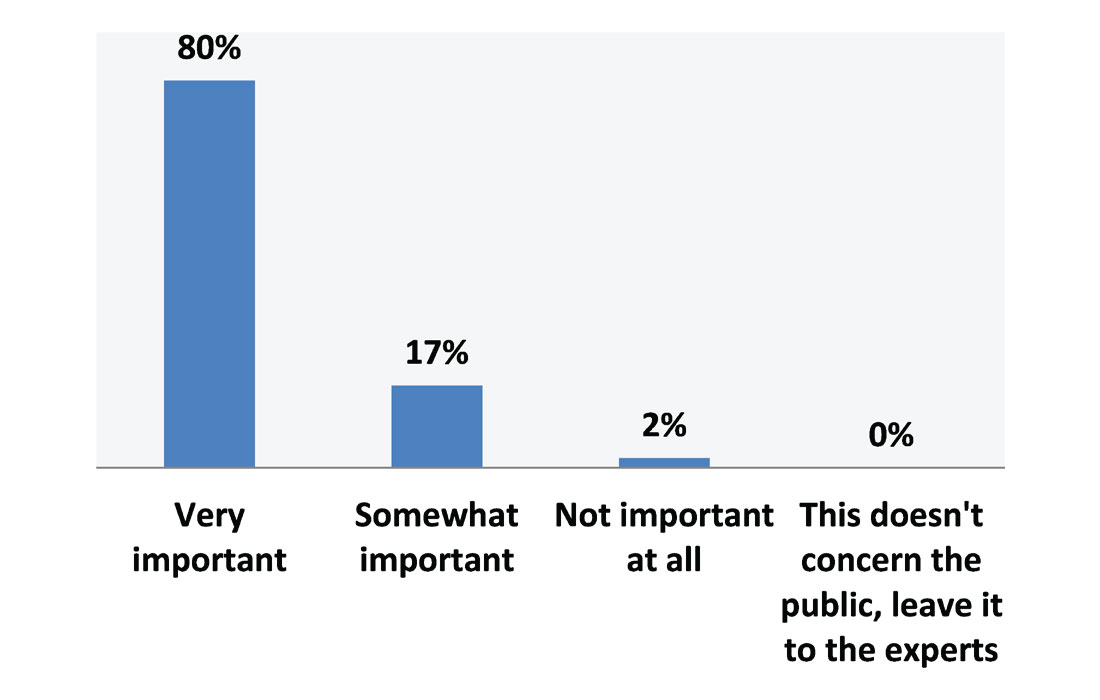

Figure 11 shows the breakdown of individuals who expressed how important it is to “educate the public on induced earthquakes as a result of hydraulic fracturing”. A large number of respondents, 80%, said that it is “very important” and 17% said it was “somewhat important”. Only 2% said that it is “not important at all” and no one selected “doesn’t concern the public, leave it to the experts”.

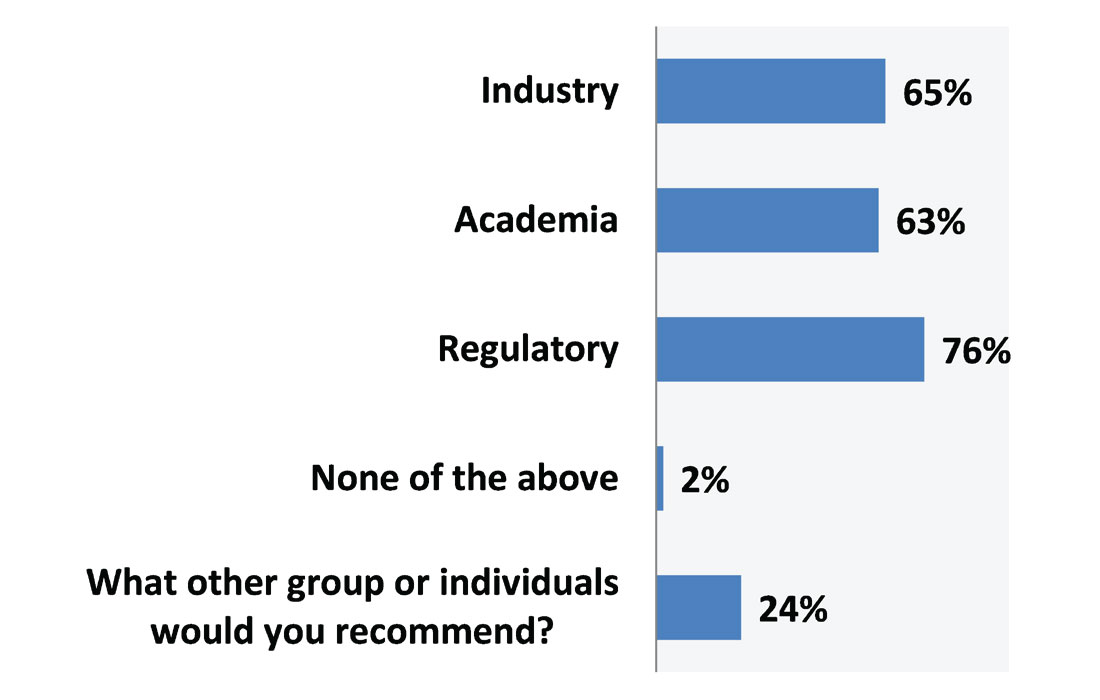

The survey then asked for feedback on who should be in charge of the education efforts on Induced Seismicity as a result of hydraulic fracturing (Figure 12). The respondent got to choose any that applied and had the option to recommend other suitable groups or individuals. Most respondents were in favor of a collaborative approach as evidenced by the selection in Regulatory (76%), Academia (63%) and Industry (65%). One comment said “we need to work together, because the industry is willing to help with the understanding, but we are considered to be biased. We need Academia and Regulatory to help with the educational efforts. We need to work together.” This echoed the sentiment of many other comments, one of which had said: “I believe that it needs to be a combination of Industry, Academia and Regulatory. Industry has the most to lose by not educating the public, Academia are most likely able to access data across companies and to potentially obtain Industry funding for research and are less prone to being ‘compromised’ by profit, and Regulatory have the power to obtain data and enact regulations that affect the Industry. A combined think-tank led by industry, but with full cooperation of the others would be a good path to follow.” Other groups recommended to be involved in the education efforts were non-government organizations (NGO), the Army Corps of Engineers, professional geoscience societies and an advisory board of industry experts to be a resource for regulatory bodies, but one that does not include microseismic vendors. One individual (2%) from the population selected to have “none of the above” involved.

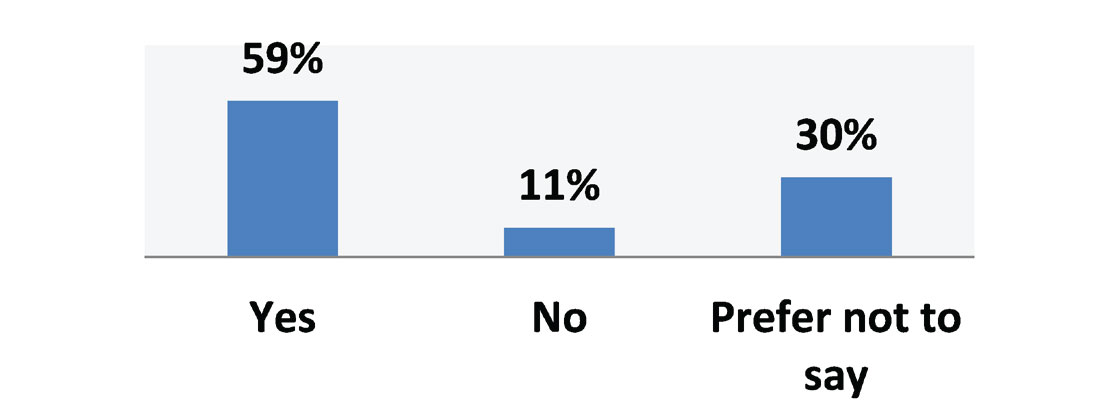

Lastly, the survey asked if the individuals’ organization would be in favor of participating in a collaborative industry effort to effectively deal with criticism, educate the public, etc. (Figure 13). Fifty nine percent (59%) of the respondents said “yes”, 11% “no” and 30% “prefer not to say”.

Discussion

Even though the target audience was different for the two surveys, the data collected was from a representative sample of individuals affected by the topic of IS. The November 2013 and August 2014 surveys contain varying information, but the discussion will refer to both while examining and comparing their findings.

The August 2014 survey showed there were more organizations without monitoring protocols in place than with. This suggests that either these organizations are operating in areas with low risk of inducing seismicity or where monitoring protocols are not enforced. Note the surveys did not distinguish between monitoring and operational protocols. Monitoring protocols pertain to developing a response plan whereas operational protocols would establish preventative measures. Research into mitigating factors causing IS related to hydraulic fracture activities is not conclusive. Studies have shown that induced seismicity caused by waste/salt water disposal can be reduced by reducing rate and/or volume injected (Majer et al., 2012, BCOGC, 2012). These types of mitigations have not been shown to be effective for hydraulic fracturing-related induced seismicity, as some instances of IS have been detected days after the treatments have finished. The lack of understanding of mitigating factors may be one reason some organizations are hesitant to generate an operational protocol, but monitoring protocols can be improved so that risks are mitigated and understood better.

The AER bulletin and Subsurface order issued Feb 2015 for the Fox Creek area of the Duvernay requires all operators in the indicated area to monitor for induced seismicity down to 2.0 local magnitudes, in additional to other requirements (AER, 2015). Operators conducting hydraulic fracturing or disposal activities in other areas of Alberta and BC may not have the option to monitor in the future, as regulations change.

With regards to those who have experienced events that were considered to be induced, most of the respondents said “no”. This could be because no monitoring systems were installed or companies were operating in regions with a low probability of generating IS. Still, over a quarter of the respondents had experienced events considered to be induced and associated with hydraulic fracturing activities. This could be because these operations were happening in high risk areas, sizeable events were happening simultaneously during a treatment or being induced by the fracturing process among other reasons.

One comment made in the summer of 2014 survey suggests said that “sales have gone up for the equipment that measures induced seismicity”. This response reinforces the findings from the survey questions which asked if the respondent’s organization had protocols in place for monitoring IS. It showed an improvement in monitoring protocols from 2013 to 2014.

Over three quarters of respondents described an induced seismic event to be naturally occurring but accelerated by man-made activities. Future research should aim to understand the frequency and relationship of this process.

Conclusions

The initiative to collect and analyze the survey results presented in this report came from a number of stakeholders from the Oil and Gas industry concerned about the economy and environment. The data provided input for companies to initiate and advance operational and monitoring protocols.

The Oil and Gas Commission (OGC) has generated two reports on IS for the Horn River Basin (BCOGC, 2012) and Montney Trend (BCOGC, 2014). Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Geoscience BC and the BC OGC have hired a Seismologist specifically to research IS in the BC region in order to investigate the source and cause of IS. The Oklahoma Geological Survey (OGS), and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) are researching IS. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has new reports on IS that came out Feb. 2015 (EPA, 2015). The new subsurface order released by the AER for the Fox Creek area will require Operators who have monitoring and operational protocols in place to improve upon them and those who do not to come up with a plan and begin implementation immediately.

There are several education efforts underway too. The University of Calgary’s Microseismic Industry Consortium (MIC) research is ongoing. Phase I of its research was directed toward microseismicity from hydraulic fracturing and is being transitioned to Phase II. Phase II will focus on acquiring, processing and interpreting passive seismic data, Geomechanics and Induced Seismicity.

To address public and environmental safety, Stanford Centre for Induced and Triggered Seismicity (SCITS), is an industrial affiliates program to help companies develop a better understanding of the science of induced and triggered earthquakes associated with different types of activities and a context-specific consensus risk management framework tool kit. The public needs assurance that energy and mining related activities do not pose undue risk of injury or property damage. It aims to show risk is being effectively managed by the industry and monitored by regulatory authorities and that information about potential risks of proposed activities are being accurately represented.

All respondents from the November 2013 survey unanimously agreed to have another forum like it in the near future. Likewise, subsequent surveys could expand participation to go beyond the CSEG members and forum attendees.

Acknowledgements

Input from the members of the CSEG/CGF MSSC was greatly appreciated: Chris Szelewski, Shawn Maxwell, Bill Goodway, Jason Hendrick and Paige Mamer. Both surveys were issued through Survey Monkey®.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article