Who of us would not be glad to lift the veil behind which the future lies hidden; to cast a glance at the next advances of our science and at the secrets of its development during future centuries? What particular goals will there be toward which the leading [geoscientific] spirits of coming generations will strive? What new methods and new facts in the wide and rich field of [geoscientific] thought will the new centuries disclose?

Adapted from David Hilbert (1902)

Introduction

Some time in 2012, we started to feel like we – those of us in this industry – were missing an opportunity (ageo.co/conffail). Some big conferences have five or ten thousand attendees. But that’s all most of them are – attendees. Not participants, or contributors, just spectators. They mostly sit in the dark listening to talks that sounded more interesting in the program, or wandering fuzzy-eyed past posters that took days to make, or having rushed conversations in the hall with people whose name they can’t quite remember and still don’t know because their badge was facing the wrong way around.

The missed opportunity was – and continues to be – making more of the fact that there are five or ten thousand geoscientists gathered in one place with a week to spare. That’s about five careers’ worth of productivity. Instead of listening to the past work of a few, let’s all of us do something useful together – something that lasts, something that does justice to those 5 careers, beyond spending $30,000 (I’m serious) on horrible coffee. Let’s take advantage of the fact that you couldn’t hope for a greater breadth of experience than the crowd that is already gathered. Let’s connect people through jointly working common problems, in addition to just networking in corridors, so that they build real relationships that matter.

This proposition is all very grand but potentially appears as just so much whining and starry-eyed idealism. What can we actually do? Well, there are dozens of things we can try (ageo.co/confexpt), so we picked one. Here’s how we invited people to an experiment at the GeoConvention in May 2013. This invitation appeared in the conference programme, in a blog post on our site

(ageo.co/unsesh), and in an email to about 100 Calgary geoscientists we know and respect:

“The Unsolved Problems Unsession at the 2013 GeoConvention will transform conference attendees, normally little more than spectators, into active participants and collaborators. We are gathering 60 of the brightest, sparkiest minds in exploration geoscience to debate the open questions in our field, and create new approaches to solving them. The nearly 4-hour session will look, feel, and function unlike any other session at the conference. The outcome will be a list of real problems that affect our daily work as subsurface professionals – especially those in the hard-to-reach spots between our disciplines. Come and help shed some light, Room 101, Tuesday 7 May, 8:00 – till 11:45.”

The unsession was one small but deliberate experiment in our technical community’s search for excellence and innovation. The idea was to get people out of one comfort zone – sitting in the dark listening to talks – and into another – animated discussion with a roomful of other subsurface enthusiasts. It worked: there was palpable energy in the room. People were talking and scribbling and arguing about geoscience. It was awesome. See for yourself in our YouTube video (youtu.be/9LdVVwUbiX4).

This event was not just about collaboration, knowledge sharing, or creativity. Soft skills like these aren’t important as ends in themselves. They help us get better at two things: excellence (your craft today) and innovation (your craft tomorrow). Soft skills matter not because they are means to those important ends, but because they are the only means to those ends. So it’s worth getting better at them. Much better. That’s what this event was about.

We started planning the session in about September of 2012, but moved slowly at first. We knew we wanted to gather lots of people and have a semi-structured discussion about unsolved problems, but the process was fuzzy. It took several rounds of brainstorming between ourselves and with professional facilitators to fill in some details. You can see the agenda we settled on in the wiki page at ageo.co/unsession.

The event

Breaking ice

One of the main purposes of the morning was to expose the diversity of backgrounds and opinions in our industry, and show how diversity of opinion is a powerful driver of innovation. So, after people had picked up nametags that reflected their main area of interest (geology, geophysics, petrophysics, or other) and sat down at a table, we breezed through a short welcome message, and then asked who people were. At the time of the poll, there were 32 people in the room (as more attendees straggled in we eventually had 33 geophysicists and 9 geologists, out of 51 total visitors to the session). Here’s who was there, as a number and as a percentage:

| How many geologists? | 3 | 9% |

| How many geophysicists? | 22 | 69% |

| How many petrophysicists? | 0 | 0% |

| How many under 35 years old? | 9 | 28% |

| How many women? | 5 | 16% |

| How many work international plays? | 3 | 9% |

| How many work unconventional? | 9 | 28% |

| How many are managers or supervisors? | 5 | 16% |

Clearly, before the next event, we need to be sure to reach out to other disciplines! Evan and I know a lot of geophysicists. Either that or the event had more appeal to geophysicists for some reason.

After these preliminaries, we wanted to get people talking to each other as quickly as possible through a ‘rock exercise’. So the first challenge to the tables was to provide descriptions of two rock samples provided by us. These rocks provided a very tangible linkage to our science; yet, as always, were very open to interpretation. Some people, especially geologists, were affronted at the simplicity of the task, but in our humble opinion no table excelled at the challenge. For example, only one table drew a picture, and there were only two quantitative rock property estimates. On the other hand, there was some ad hoc geomechanical stress testing, the results of which were unclear!

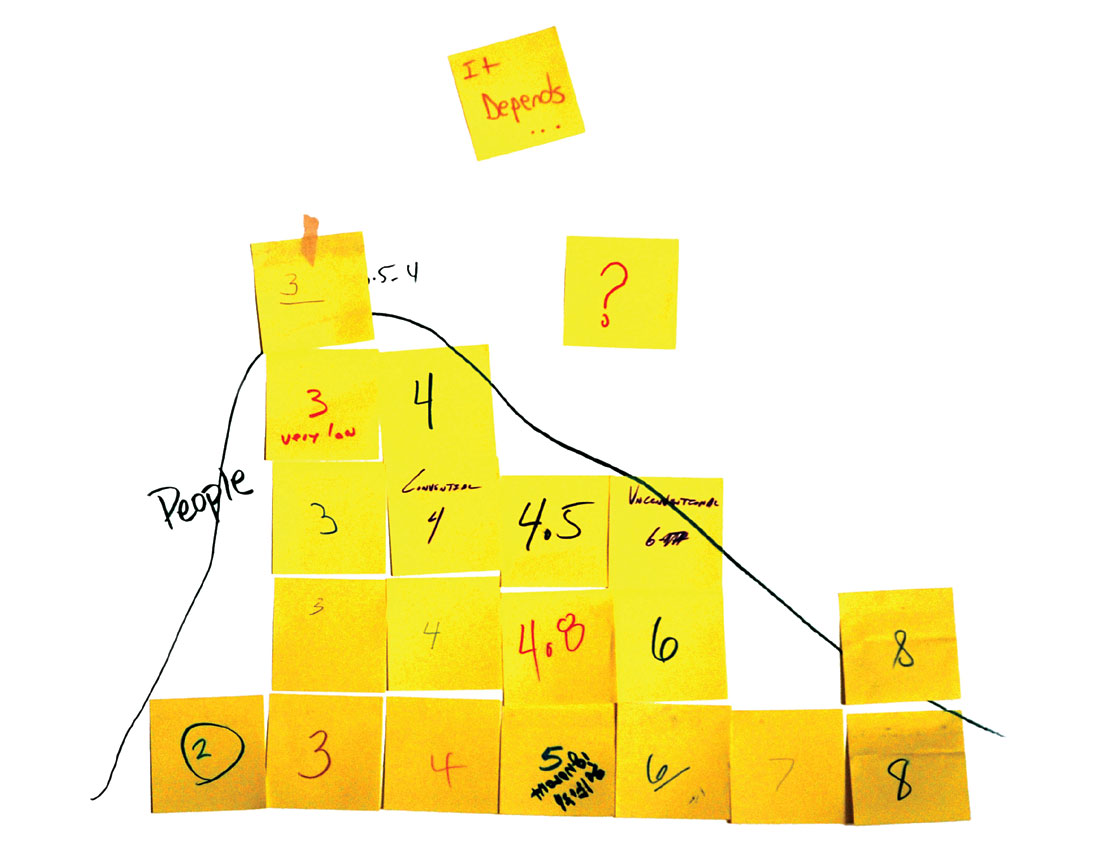

The experience led nicely to discussions about integration, as we asked, “How does our industry score on integration and collaboration?” The result: a log-normal distribution with a mean of 4.6 (out of 10), but a caveat that ‘it depends’ (remember, it was mostly geophysicists in the room!). The consensus was that the industry does some complicated things very well, but there was plenty of room for improvement.

Finding problems

The next challenge was bluntly put, and provided the real meat of the morning. We asked:

“An anonymous donor has provided $1 billion for this room to solve a problem, or some problems, in exploration and development geoscience. And it’s us that will be solving them – the people in this room, with our ingenuity and skills and diversity. And we’ve got 10 years. Essentially, we can tackle anything. It’s up to us to decide. So what will we work on? What are the most pressing questions, the big unsolved problems that we want to work on?”

The purpose of this slightly oblique way of expressing the question was to make it as tangible and practical as possible, as opposed to an abstract, academic exercise. And the numbers–$1 billion, 10 years– were really just intended to be large numbers that suggested limitless possibilities. We wanted to get at the greatest aspirations of the people in the room.

A note on that last detail: ‘the people in the room’. There’s a principle in one style of ‘unconference’, so-called open space technology (which itself was part of the inspiration for the design of the unsession). In the open space concept, there are some key ideas:

- Whoever comes is the right people.

- Whenever it starts is the right time.

- Wherever it happens is the right place.

- Whatever happens is the only thing that could have.

- When it’s over, it’s over.

These ‘rules’– which you can interpret as freedoms – help ensure that people don’t fret about who’s there or not there, how long things are taking or not taking, or whether they are getting the ‘right’ answers.

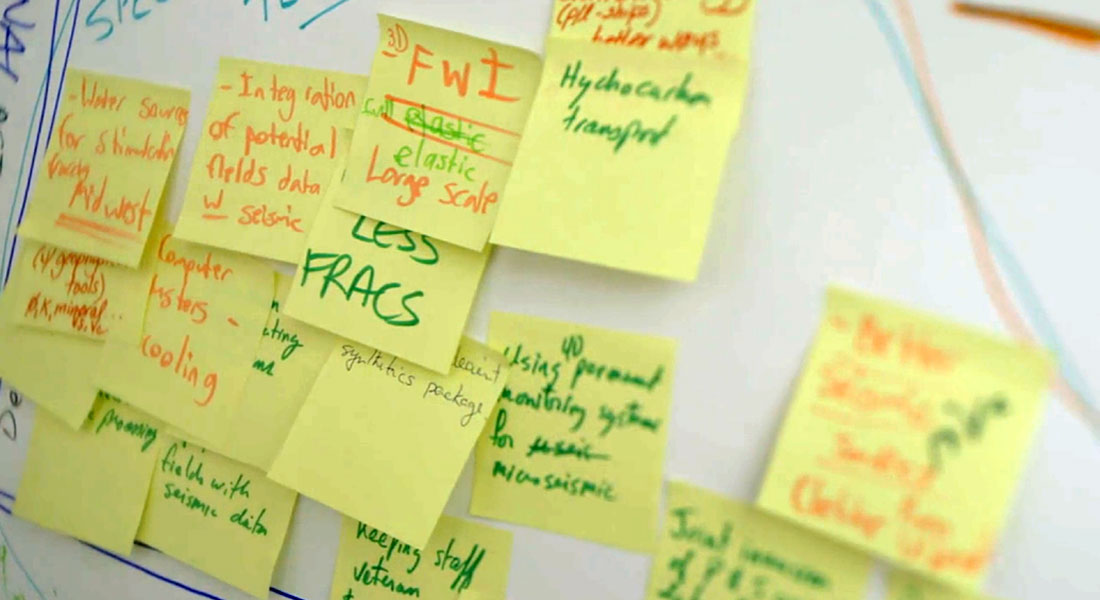

We let the teams run with their ideas for a while, with designated table hosts capturing everything. About 145 problems were scribbled onto sticky notes and plastered onto the tables (ageo.co/unsessionproblems), ranging from improving seismic resolution to doing more about marine mammals, and from gas hydrates to mantle hydrocarbons. Some problems were very specific (e.g. ‘What variogram geometry should we use for each [property] if we want to build a proper model?’) to the rather vague (e.g. ‘Trust’).

We then asked everyone to change tables. This move was one of those love/hate moments – some people regretted leaving ‘their’ problems behind... but this was the point, and others relished the change. At their new tables, we asked the tables to consider the problems on the tables on two dimensions: how far-reaching is the problem (e.g. is the problem local or global? Play-specific or general? Infrequent or every day?), and how many disciplines does the problem affect (getting at how integrated we have to be to solve it). We tried to avoid getting at value, per se, since even local problems only affecting one discipline might carry high value. The idea was to identify widespread problems of integration – as the convention’s theme, that was our purpose for this event.

At the end of the matrix sorting, we asked the tables to select three problems from the far-reaching, integrated quadrant, and put them up on the wall. Then each participant was given three sticky dots as votes, and asked to distribute them among the problems during the break. In our ‘dotmocracy’, one might vote for one thing three times, or three things once.

Here are the top 10 problems from the unsession, based on votes received:

| Problem | Geoph | Geol | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less secrecy, more sharing / Free the data | 9 | 6 | 5 | 20 |

| Improving seismic resolution | 14 | 3 | 0 | 17 |

| Acceptance of error – live with it | 7 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| How to get more oil & gas from old fields | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Water – need to develop national and global understanding and policy | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| How to resolve damage from resource extraction vs environmental protection | 2 | 5 | 0 | 7 |

| Lack of science (E&P) acceptance in society | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| Gas hydrates development R&D (×4) | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Sustainability, right to operate, energy life cycle | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Applicable technology transfer from medical & other industries (×2) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

We plan to hone and augment this list at future events, and hope the community will take it up and develop it further. We hope it will help inspire new MSc and PhD projects, new software startups, or service offerings. These are the big problems, and it’s up to this community to address them.

Solving problems

After first exploring some of the problems of integration, then surfacing problems, and then filtering and classifying them, we moved to solutions. Not real solutions – these are big unsolved problems – but some imagining what solving them might take.

First we moved people again. We selected 5 of the top problems from the filtering exercise, and distributed them among the tables. Then we asked people to go to whichever table they felt they could contribute most to. The ‘law of two feet’ applied: if you are not contributing or learning, you go somewhere else.

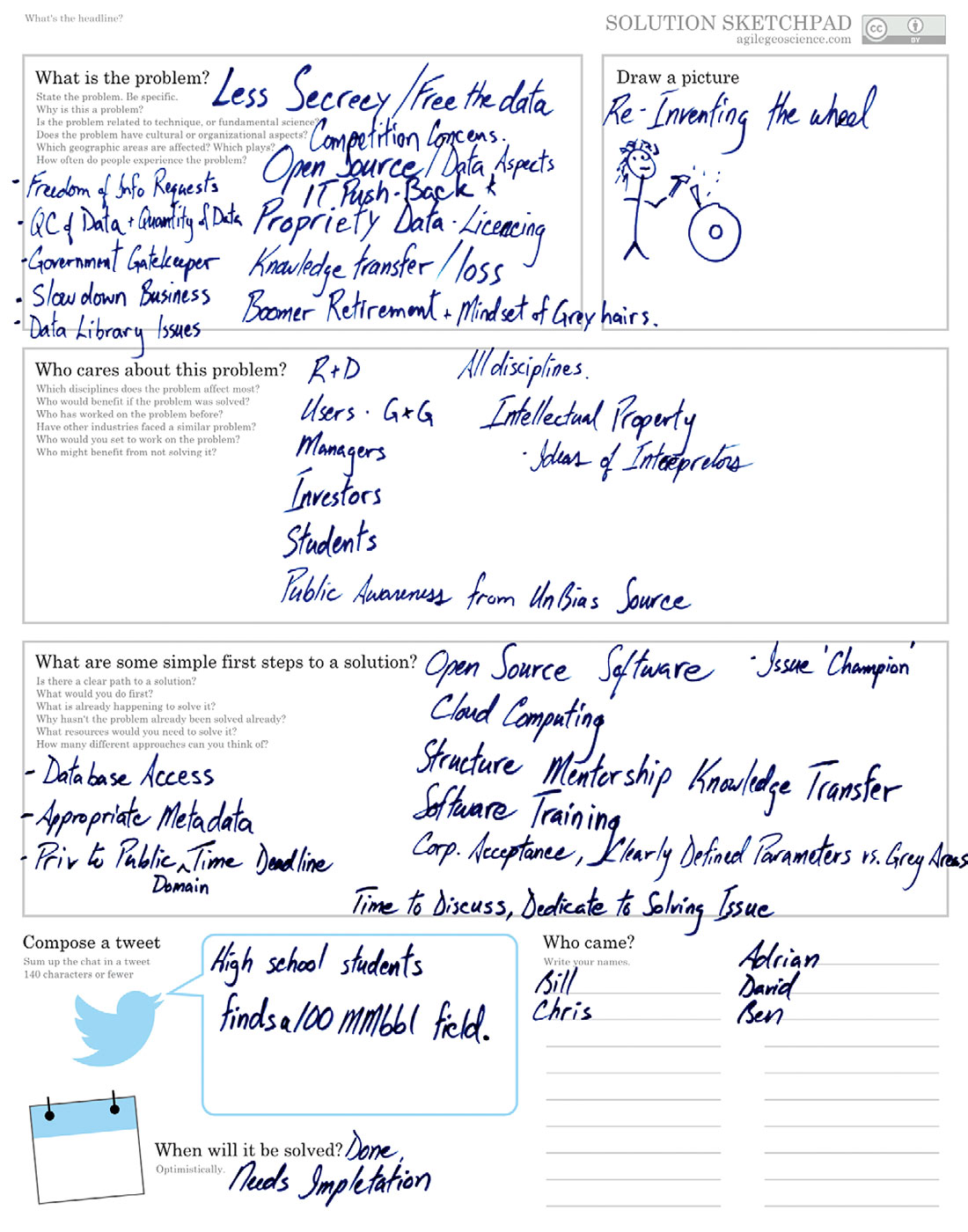

We asked the tables to discuss some specific questions about their problems:

- What is the problem? Define it; be specific. Why is it a problem?

- Who cares about this problem? Which disciplines does it affect most?

- What are some simple first steps to a solution? Is there a clear path?

- When will it be solved?

- Who worked on this?

Rather than leaving people to capture their conversations ad hoc, we provided a ‘solution sketchpad’. This also helped guide the discussion and keep it relevant. You can see the completed canvases at ageo.co/unsession, and download a blank one at ageo.co/solutionsketchpad. Of course, we barely got started, but it felt good to leave the morning on a crescendo of energy and creativity.

To summarize their work, we asked each table to compose a tweet – a 140-character précis of the problem and its solution. Since any substantial summary was impossible in the time available, we reduced the requirement for reporting back to this quantum of information.

Outcomes and feedback

All of the material we gathered – posters, sticky notes, solution sketchpads, and so on – was scanned and uploaded to the wiki page at ageo.co/unsession. Please take a minute to look at some of it, because it’s quite amazing what a group of people can achieve in under 4 hours.

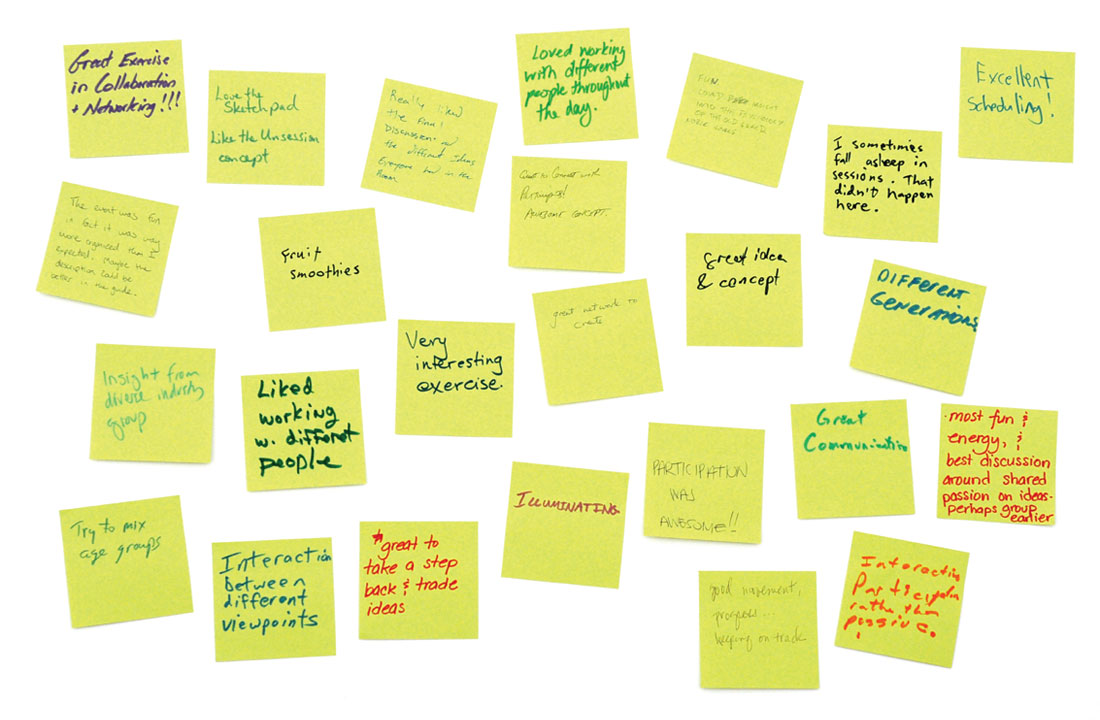

In addition to the more scientific outcomes, we solicited feedback about the event itself. On their way out of the room, the participants left sticky notes on the door, capturing something they liked about the morning. Here’s a selection:

- Great exercise in collaboration and networking!!!

- Love the sketchpad; like the unsession concept.

- The event was fun, in fact is was way more organized than I expected.

- Great to take a step back and trade ideas.

- Participation was awesome!!

- Fruit smoothies. It was clear that people enjoyed the diversity in the room:

- Fun. Loved insight into the psychology of the old guard.

- Really liked the final discussion and the different ideas everyone had in the room.

- Loved working with different people throughout the day.

- Different generations.

- Insight from diverse industry group.

- Interaction between different view points.

And our favourite:

- I sometimes fall asleep in sessions. That didn’t happen here.

We also asked people for one thing they’d change. A few of the responses:

- Need more time to really grapple with the problem in the end.

- More drawing.

- Larger room if fully attended.

- More time to define the solutions to the problem during the last part of meeting.

- More space to hear everyone when group is large. More people!

- Would love to see a greater representation of different disciplines.

- More space at tables for brainstorming (same number of people).

It seems some people are comfortable with the big picture, while others would have preferred to get down to the nitty-gritty. Maybe we need two kinds of event:

- Didn’t like the world broad topics.

- Felt very high-level... hard to get my head around ‘how could we solve this?’

- Not enough big-picture, fundamental problems. No-one cares about ground-roll.

- Focus the problems.

- [More] detailed real problems.

There was a clear indication that we could have done a better job describing what we were going to do ahead of time:

- More promotion – showed up by accident!

- Maybe the description could be better in the guide.

- More exposure!

- Advertising!

Now that we know a bit about what we can reasonably expect to do in a session like this, the blurb in the program will be more bullish, and more conspicuous. Some of the things we learned:

- These sessions work, people enjoy them, and they have tangible, lasting outcomes.

- You can’t expect people to come and stay, unless you hold the event as a workshop.

- The team of sparky table hosts was essential to keeping the conversations moving. Careful selection of these hosts is critical.

- A professional graphic recorder would be a useful addition to the team. This part was hard.

- We deliberately wanted to experiment with a lot of methods in this event, but a full day would be more comfortable for as varied an agenda as ours.

Cost

The event was part of the GeoConvention, so many of the actual costs were covered: room rental, programme (not that we really used that), volunteers (ours were used as table hosts), audiovisual equipment and support were all provided. We’re very grateful to the Convention organizers for the chance to run this session.

Everything that wasn’t covered was sponsored by Agile Geoscience – an easy decision-making process for us! Because we were asking participants to stay in the session, if possible, rather than leaving for the ‘Breakfast with the Exhibitors’ upstairs, we provided refreshments. We tried to select healthier, less typical things from the Convention Centre’s menu, which tenants are compelled to use. This cost about $1000. We probably overdid it a bit, but this seems preferable to underdoing it.

We also wanted to capture everything in video and photos. In the end, you have to go for one or the other, so we leaned towards video. Excellent service was provided by Craig Hall Video and Photography (chvideophoto.com), and cost about $4000. Three-minutes of video is an efficient way of getting a message across; it probably tells a better story than this article.

We spent about $400 on stationery, but almost all of it can be used many more times. And we made some rather good stickers for the participants, at a cost of about $200.

As consultants, we ought to factor in our time, but this would be rather complicated. A very rough estimate puts the organization time at about 40 person-hours, spread over about 9 months. Lots of ‘stewing time’ in between meetings and brainstorms helped. On top of that we spent about 20 hours in execution mode right before the event, making things, preparing materials, and so on.

What’s next

At the end of the unsession, we promised to collect the content from the morning on the wiki, and to write a short report about the event. Both of these things we have done.

And there was another thing: we proposed to gather people together to build something – some kind of hack session, sometime in the winter. But one piece of feedback about this proposed session was “Do the hack session in the fall; we are very busy during winter drilling and seismic season.” We hadn’t thought much about this, but it did nudge us towards doing something a little sooner, though on a smaller scale. So the weekend before the SEG Annual Meeting, we hosted a hackathon in Houston. Teams created mobile or web apps that address some aspect of uncertainty in applied geophysics. Besides the participants we had a few curious visitors, including the president-elect Chris Liner and some SEG board members. Read more about it at ageo.co/geophysicshackathon.

We also said we’d run another unsession next year, and probably at some other conferences too. These are all on our horizon for 2014.

One final thing. If you’d like to bring new energy to a meeting, workshop, conference, or even corporate environment, we’re more than happy to share more of what we learned on this sunny morning in May.

Acknowledgements

A huge thank you to Carmen Dumitrescu, Milovan Fustic, and the rest of the technical committee for fearlessly offering us the opportunity to host the unsession. Shauna Carson of CSPG did her job brilliantly and expediently. Tim Merry of myrgan.com gave us indispensable advice before the event. Craig Hall was exactly the video professional we needed, and excelled in every way. Our brave table hosts were terrific and transformed the event from our vague ideas into what it was. Astrid Arts, Tooney Fink, Eric Hanson, and Stan Lavender generously provided rock samples for the event. Tooney Fink and Mark Dahl improved the manuscript of this report. And the people who came showed unusual levels of curiosity and enthusiasm in even walking into the room – thank you all. It was an honour to be part of it.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (bit.ly/cc-by).

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article