Purpose and Scope

This talk was prepared for the fall 2005 CSEG DoodleTrain in Calgary, Canada as the invited lunchtime presentation . Unfortunately, in late August 2005 I evacuated New Orleans due to hurricane Katrina and then spent several months trying to recover; therefore, the talk was never given. Fortunately, I had a copy of this written paper in my possession, when I evacuated.

My goal was to articulate some challenges facing the North American exploration and production geophysical community that might significantly impact its future, and to suggest some possible solutions. My approach was to identify a number of issues that I perceived to be important, rather than focusing solely on one or two topics in great detail. Indeed, each of these issues and solutions is significantly complex as to merit a separate, detailed study.

Assumptions

I believe that:

- The world will remain dependent, and indeed increasingly dependent, on oil and gas for the foreseeable future; consequently, there will be an increasing demand for capable E&P geophysical staff.

- In North America, we are facing a “great crew change”: Our demographics are such that there is now a peak of geophysicists in their late forties. If the conventional staffing models persist, many of these geophysicists will have retired from their current jobs and have largely exited our industry within the next five to ten years. Our overall experience-level distribution (instead of merely looking at age as a parameter) also has significant peaks and troughs. Severance and other staff reduction programs have been partly to blame for these imbalances.

- We live in a truly global economy and society and we need to make good use of globalization. For example, the geophysical demographics in other regions of the world are somewhat different from those in North America. How can we use these differences to our advantage?

- In order to retain our mid-career geophysical staff (this is a core group with roughly six to fifteen years of industry experience), to attract new scientists to our discipline, and to encourage our most-experienced staff to stay longer in our industry, we need to develop and articulate a true “employee value proposition.” Indeed, what is there about our discipline and industry that would make someone want to work and stay here? Obviously, there may be some specificity within individual companies or institutions.

- A strong focus on the geophysical discipline is returning in some companies, rather than merely having geophysicists work on multi-disciplinary prospect development teams or asset-based teams. This is a healthy trend. A renewed emphasis on staff, skill and competence development is vitally important, and a vibrant technical training program is a key enabler.

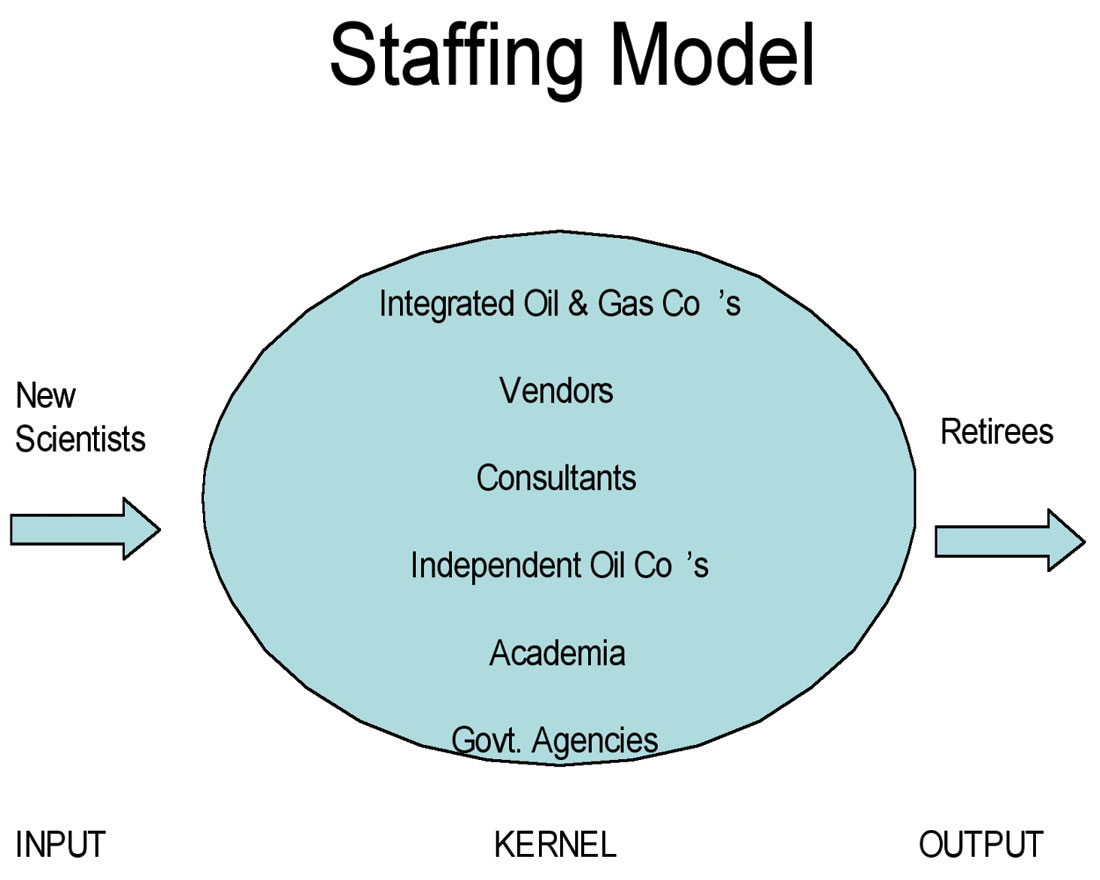

Staffing Model

Consider the staffing model shown schematically in Figure 1. Let us focus on North America for the moment and consider the impact of globalization later. Let me refer to the center portion of this figure as the “kernel.” It contains the geophysicists currently working in our overall industry. These scientists may be employed at large integrated oil and gas companies, by independents, by vendors/service companies, as geophysical consultants, by academia, at governmental agencies and by others.

Flowing into the kernel is the input – the supply of new geophysicists. Rather than focusing solely on the traditional input, namely students from geology/geophysics departments and who hold citizenship or permanent resident/landed immigrant status, I believe that we shall need to expand our search to include those who have been trained in scientific disciplines other than geophysics and/or with a broader immigration status. I consider these to be excellent examples of taking advantage of diversity of education and culture.

Flowing out of the kernel are the retirees (and others) who leave the industry prematurely, in most cases never to return to our industry. We need to break this paradigm whenever possible.

Kernel

The great crew change is an average phenomenon summing up all the geophysicists in the kernel regardless of whether they work for oil companies, academia, and so on. There are quite a few geophysicists (and scientists in general) in academia and at certain governmental agencies (such as the US Geological Survey) that elect to continue working into their sixties. At the very least, we should make optimal use of these experienced staff and indeed of all late-career staff. In addition, we should seek to understand the positive factors (and not the negative ones like a career with persistently low pay) that encourage such staff to continue working, while their counterparts in the kernel depart the industry by their mid fifties. And we should articulate these factors in our employee value proposition.

In an ideal world, each of the entities in the kernel would focus on what it did best and what was truly most important to its existence. One might term these focus areas “core competencies.” I believe that many geophysicists would agree that we are not yet at that stage of maturity as an industry. There seems to be a disproportionate concern at individual companies or institutions toward building a competitive technical advantage, and protecting intellectual property, in an unrealistically large number of geophysical sub-disciplines. Is this necessary or healthy? I believe it is not.

In many cases, although admittedly not all, it is my experience that the key to success by an individual oil and gas company lies not so much in possessing advanced in-house technology but, rather success is achieved by being the best at applying appropriate technology to the business, and indeed in applying the right technology and staff to the right project at the right time. Companies with a strong functional organization (with a Chief Geophysicist and supportive others), in addition to multi-disciplinary asset-based teams, may be best equipped to have an advantage in this area.

Furthermore, our oil industry projects are becoming more technically complex, globally oriented, and capital intensive. Much of the easy oil and gas has already been found. A key to success going forward will be the strong integration of a number of key geophysical technologies with those from other subsurface disciplines. For example, exploration and appraisal success is no longer so heavily dependent solely on geophysical measurements. Rather in some provinces it requires combining a strong understanding of the regional geological framework, with advanced seismic imaging technology, stratigraphic interpretation methodology and software, rock property trends and modeling capabilities, seismic amplitude versus offset analysis, and other key technologies.

To enhance field development and production, seismic volume interpretation, visualization tools, seismic inversion, 4-D seismic and other such technologies can be keys to success, when properly tied to static reservoir architectural modeling and dynamic reservoir simulation.

Although we would like to reduce the cycle time of such projects for economic reasons, the reality is that many of these integrated projects span years. For this reason, and others, it makes sense to keep a multi-disciplinary, multi-technology team together, intact and employed, even during downturns in the oil industry. Staff layoffs and severance programs have been detrimental, in this regard.

Our industry also seems to be too siloed in the kernel. We need to explore possible synergies between the entities. Creative partnerships or ventures, for example between vendors and oil companies to jointly develop and deploy advanced technologies, or innovative efforts to share staff and projects more fully between academia and companies, could go a long way toward optimizing the kernel. Our late career staff or current “retirees” might be the glue that could help to achieve this goal.

Also, I believe that in some joint ventures between oil companies, the division of technical and operational responsibilities is not always optimal. We have to work to improve this situation. This involves sharing technology better and building trust. To the extent that joint ventures are necessary to reduce risk, all reasonable avenues should be explored toward enhancing the profitability of the overall joint venture.

Input

I believe that high school science education in North America is in need of serious nurturing. Our oil industry societies, universities and others should enhance their role in this area. We should provide more speakers, mentors, science fair judges, summer field camps, university entrance scholarships and other forms of encouragement. High school students should be invited more frequently to experience our industry conventions, especially the exhibit areas. The science and mathematics skills of the more diverse members of the student population should be especially nurtured. And high school teachers should be employed in meaningful, well-paid, summer assignments in our industry, so that they can have a better appreciation of our work and the technical and interpersonal skills required to support it.

During the past several years, at the very least, the preponderance of geophysicists who entered our industry from universities was formally trained in geophysics. As such, these geophysicists were able to make contributions to our industry relatively quickly. I believe that, going forward and in view of the great crew change, this model will not suffice. At least a few larger oil and gas companies have recently been hiring, as prospective geophysicists, promising scientists trained in other disciplines including, but not limited to, physics, applied mathematics or engineering. I believe that this model will be increasingly necessary in the future. Simply put, we need to open up the supply of bright scientists into our discipline.

Consequently, it will be increasingly important to train these scientists to quickly fill in gaps in their geoscience backgrounds. Large oil and gas companies can sometimes address this need internally with targeted, in-house training programs. But in general there will be an opportunity and market for universities, and oil-industry trainers, to jump-start these non-classically trained geophysicists. Experienced oil industry staff could play a key role there. Although seemingly new to geophysics, this model is very similar to that of executive MBA programs that fill in gaps of many oil industry executives and leaders who received little or no formal management training.

Indeed, I entered the oil industry about thirty years ago with essentially a physics background, although, I took one graduate level geophysics class at university prior to joining Shell. I was enticed to join Shell by other physicists whom the company had hired, and then trained, before me. The learning, which I believe generalizes, is that we should encourage our current geophysicists who entered our field from other scientific and engineering disciplines to lead others from their parent discipline to become geophysicists. These experienced staff could give technical seminars in key non-geophysics departments in academia, encourage sabbaticals there by industry staff and vice versa, and so on, in order to bring more scientists to our industry. More summer internships in our industry could also be beneficial. And, above all, we need a clear employee value proposition to underpin all this.

Many entities in the kernel prefer, for a variety of well-founded reasons, to recruit and hire citizens of their nation or permanent residents. However, there is an increasing population of bright foreign nationals who come to North America to study and who wish to remain here after completing their education. I believe that we need many of these scientists to stay and be employed in our industry. We should be more aggressive in articulating this need to government agencies and in appropriately hiring such scientists, starting at the very least with those trained in the geosciences.

Again, I speak from experience. I came to the United States to earn my Ph.D. degree but, having earned my degree, I wanted to stay and work here afterward. I did not yet have a permanent resident visa. Shell was one of the few companies willing to hire me. As the son of a native-born American citizen, it was not long thereafter that I was able to get my “green card.” Nevertheless, I am grateful that Shell was willing to take a chance on me and, it turned out, the company was very happy that I came to work there.

Output

The average retirement age for oil industry geophysicists in North America is about fifty-five years. There is a desperate need for our staff to work longer, whenever possible. This need is, of course, not unique to geophysics, although our particular need is acute. We should develop staffing models that allow late-career staff to work on a more flexible, part-time basis, with continued benefits. Again this should be part of the employee value proposition.

At the very least, a good work-life balance is a pre-requisite for employees wanting to work past fifty-five, and indeed for scientists to want to enter and remain in our industry. Other enablers might be a more flexible working environment, including some possibility of working from home (“telecommuting”). Late-career staff should be given meaningful, interesting assignments, perhaps focused on mentoring less-experienced staff (but only for those experienced staff who have that inclination and ability), or on solving difficult technical problems, or representing their companies in joint ventures with others in the kernel of Figure 1, and so on. And, please let’s stop forcing, or even worse paying, our staff to retire.

Some late-career staff might wish to redeploy as consultants either at their present companies or within the industry in general. This could be critically important and should be encouraged, whenever possible.

Other late-career staff may wish to migrate to or from academia, and our industry should facilitate this whenever practical, as well, for the overall good of the discipline.

Global Issues

Some experienced North American geophysicists are currently being actively and increasingly recruited to work in other regions of the world. I had an opportunity to spend part of my career, albeit a small portion, living and working in Europe and I found these assignments to be very beneficial. I returned to North America afterward with many new technical ideas to try at home. For those who are inclined to work overseas, the romance of living in a foreign land, learning to speak a new language or to experience a new culture may also be tremendously rewarding, not to mention the financial incentives. A recent trend, however, unlike my personal experience, is for quite a few American geophysicists who moved overseas to be reluctant to return home for many years. One reason given has been their perceived “poor condition” of the school system back home.

Perhaps we can balance some of this staff outflow? The challenge will be to entice geophysicists from other regions to impact North America whenever practical. In some cases, this may mean moving such staff here. In other cases, some of the work could be done at a distance.

Indeed, let’s devote more thought to ways to make better use of the global geophysical talent pool and not just for the benefit of our region. International geophysical societies should play a leadership role in this area.

Conclusions

Exploration and production geophysics in North America is facing a crisis. Our challenge is to make best use of our existing staff, to encourage our late-career staff to remain longer in our industry and to make the best use of their experience and skills, and to attract the best and brightest students – irrespective of parent discipline or visa status – to join us as geophysicists.

A key enabler, going forward, may be to foster a strong geophysical disciplinary focus in our companies and institutions, in addition to an integrated, multi-disciplinary team approach. Our staff will need to be very strong technically and know the relevant technologies and resources to apply to the right projects at the right time. In our work processes, geophysical technologies will need to be properly integrated with those from other scientific and engineering disciplines.

Severance and other staff reduction programs are shortsighted and have overall been detrimental to our industry. We must stop encouraging valuable staff from leaving.

Building alliances between oil companies, vendors, academia and others will also be essential going forward. Our late-career staff could help to make this happen.

We live in a global society. The North American region is facing an impending crew change that may be less severe in other parts of the globe, and we are even losing some of our experienced staff to other regions. We need to consider how and when to engage staff globally to best impact our business.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article