Abstract

It is a yearly exercise that plays out for every oil and gas company in Canada. Due to National Instrument NI 51-101, producing oil and gas companies report their reserves on an annual basis. Through this process, companies wish to have their efforts and achievements recognized as having added value to the organization. Assessing the value of a corporation’s proven and producing reserves, its proven and non-producing reserves, along with the probable reserves, the possible reserves and perhaps even the resource potential, has a material impact upon a corporation. These reserve numbers are then used to estimate net asset value. The company discloses this information as it is used in part by the capital markets and the public to make investment decisions. The ability for a client company to provide data and key information can reduce overall costs. The quality and extent of the technical work performed can add confidence to a reserve auditor. Historically, the contribution of geophysics through the use of seismic data has had limited impact, often just defining the areal extent of the reserve for volumetric analysis. Technological developments during the past couple of decades suggest that it is possible for seismic data to be used to predict reservoir properties through reservoir characterization. These predictions, if well calibrated with a high degree of confidence can materially impact reserve bookings, particularly probable and possible reserves, not to mention resource potential. A reserve auditor can provide expert guidance regarding what needs to be done to further recognize value to a corporation.

Background

The professional who is cast into the role of being part of a reserve audit team cannot take their position lightly. At the conclusion of their work, a report is written which requires professional accreditations to be declared and a professional stamp applied to the report. The reserve auditor needs to be able to defend their position under the guise of industry standard practice and feel confident with the report findings. This is one of the instances where all technical professions, and yes, even geophysics, addresses public interest. Client companies may tout their reserve additions for a given year in a press release which could in turn affect capital markets and investor interest to purchase or sell shares in a public corporation. Hence, being able to accurately and concisely review, audit and evaluate a company’s properties to assess reserves and net asset value, is a critical part of the oil and gas business.

Proved reserves represent the hydrocarbon volume in place that can be estimated with reasonable certainty to be commercially recoverable from a known reservoir under existing economic conditions, operating methods and current government regulations. Proven reserves are reported under two categories, namely proven producing and proven nonproducing with a likelihood of recovery being ninety (90) percent. These are often referred to as “1P” reserves. Probable reserves represent the volume of hydrocarbon in place that is equally likely that the actual remaining quantities recovered will be greater or less than the sum of the estimated proved plus probable reserves. Hence a fifty (50) percent confidence factor is applied to this category. The combined proven plus probable reserves are often referred to as “2P” reserves. Possible reserves represent the hydrocarbon volume in place that is less likely to be recovered than probable reserves. Under a probabilistic approach, the likelihood of recovery is better than ten (10) percent. Combined proven plus probable plus possible reserves are referred to as the “3P” case. All reserve auditors are guided by the same rules as outlined in the Canadian Oil and Gas Evaluation Handbook (COGEH). All companies consider parameters such as pressure, porosity, permeability, production technique and methodology, future capital requirements, production economics and the economic viability of the reserves.

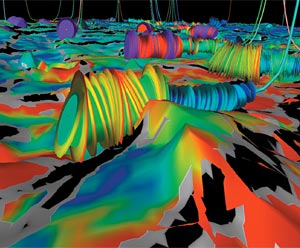

The engineering profession drives this process and forms the principal component to any such evaluation. After all, the engineering profession is a science that deals with more definitive factual information than say geology or even geophysics. From an engineering perspective, a well produces so many barrels of oil, gas, condensate and water last year with a flowing tubing head pressure of a given value, plus a measurable water-cut. Many things within the engineering discipline are quantifiable. For oil and gas properties being evaluated on a pressure decline basis, should enough hydrocarbon be extracted to provide meaningful results, geophysics does not play much of a role. Quite often the engineering discipline acts in isolation, perhaps invoking some supporting geologic perspective. While geophysics may provide further information and perhaps more accurately define the geometry of the field, often the benefits of applying geophysics are over-looked. For some new exploration plays with perhaps a single discovery well and no production history, the geophysical data may be the most valuable in assessing the Original Oil In Place (OOIP). However, not all plays are conducive to seismic contribution. Not all long-time producing properties even have any seismic data. Mature properties are often in a “blow-down” situation where the reserves are being harvested, and capital expenditures along with operating costs are often minimized to accentuate netbacks. In a development mode, seismic data can be used to find “sweet spots” or regions with improved reservoir characteristics that may influence the positioning of in-fill drilling or horizontal locations. This technical work, if performed with a high degree of confidence, can influence the booking of probable and possible reserves. Advances in seismic technology have also made it possible to monitor production practices through the use of time lapse 4D seismic, something which is becoming more common in the Canadian oilsands. Hence seismic data can add significant incremental value to a rather mature producing property.

Geophysics, however, and in particular seismic data, is used more often for properties requiring a volumetric assessment of reserves, properties where less than 10-15 percent of the reserves have been produced on a pressure draw-down basis, which is a key hurdle some audit companies use to determine the methodology of approach for reserve determination. These properties are either quite large in areal extent or in the early stages of development. They could still be at an exploratory or even appraisal stage. Seismic data is commonly used to quantify the size of the “tank” for these properties to help determine gross rock volume. Properties such as these may not have an abundance of seismic data or may have just 2D data available. Perhaps a 3D seismic survey has been acquired but no additional work exists beyond just a structural interpretation. Should some reservoir characterization work be conducted, this technical work could be used to positively impact reserve bookings. A higher degree of technical rigor could increase confidence associated with the presence of a reserve under any of the classification categories. The reporting of reserves is a conservative value based process when compared to an exploration effort. Professionals should keep perspective in mind. When searching for hydrocarbons, a geologist or geophysicist is cast in a role to be optimistic to showcase the potential upside of an opportunity. They are often working with industry chances of success factors of roughly 25 percent for an exploratory well. Reserve auditors are a far more conservative group because of the definition of what constitutes a reserve.

What Reserve Auditors Want

Professionals addressing the responsibilities afforded to them as a member of a reserve audit team actually want to be able to recognize a company’s achievements and declare the reserves and recognize value. To do this, however, requires a reason for them to do so. Reserve auditors wish to receive a back-up of the entire workstation project that the geologist, geophysicist and reservoir engineer were using. Often, they receive pieces of data and information in a disjointed process of data transfer. The client company cannot find data and key information. Some data is missing or not retrievable perhaps due to a loss of personnel intimate with the project. This then often leads to the reserve audit house to have to re-build projects, element by element, often having to re-format data to get it into a more reasonable form, just to be able to review the technical work and then perform an evaluation. While this gyration has a cost impact and a cycle time delay, it also does not inspire confidence from the reserve audit house at the onset of the project.

The level of technical rigor applied to oil and gas properties may vary relative to the amount and types of data available. Perhaps no seismic data exists. Perhaps the producing formation cannot be seen by modern day seismic techniques. Perhaps the field may be only partially covered by seismic control. The 2D line spacing may be inadequate to define the reservoir horizon geometry? How well is the reservoir horizon imaged and interpretable in terms of reflection continuity? Do seismic attributes help delineate the reservoir distribution and depositional environment? These are but a mere sampling of the questions in the mind of a reserve auditor while assessing the data limitations.

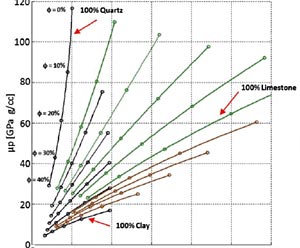

Upon review of the geo-technical work, the reserve auditor is looking for completeness and competence of the work performed so as to then assess the reserve. While the auditor may have taken a different approach to the technical issues associated with any given property, is the methodology deployed technically sound, defendable and in accordance to industry practice? Has the work adequately defined the reserve? Does the map represent the areal extent of the reservoir? What degree of confidence or uncertainty exists in the mapping? Has the client adequately defined the producing formation? Are reservoir metrics quantifiable with certainty? Can reservoir parameters be predicted with confidence? Perhaps there is a neural network study combined with an AVO study that predicts reservoir properties or pore fluid content which matches and further supports reservoir production performance? As one can readily see by this series of questions, the extent of technical rigor applied by an oil and gas company can affect an auditor’s confidence in particular when dealing with the assignment of probable and possible reserves and more so with resource potential.

Reserve auditors want to be able to simply review the work performed to conduct their analysis. Often they have to reformat data and re-build projects just to perform this analysis. If their review of the property results in shortcomings in the technical work that need to be addressed, then there is a requirement to fix the technical work to address whatever the technical issue is. Time is often of the essence as there are rules for the timing of disclosure. Hence, in such a situation, caveats often creep into the reports and the reserve auditor is less inclined and inspired to have the confidence in the work performed and they may take a more conservative stance. Sometimes these issues are left for next year’s report to address. Key insight can be obtained from a reserve auditor regarding what work or operations performed would permit the recognition of an additional reserve.

The reserve audit process can pit the reserve audit house against the client. The client wishes to have recognition of a reserve and its associated value, the auditor having to deal with the client while also telling them the truth, a truth they may not want to hear. Thought should be given whether reserve auditors should be directly engaged by the Board of Directors through their audit committee, thereby placing senior management into a role of providing information and stating their claims, as the liability for reporting ultimately resides with the Board of Directors.

Reserve auditors are really no different than financial auditors. Their roles are similar. Switching financial auditors every year would be frowned upon in North American business circles. The same is true in the reserve audit business. As properties evolve over the years from an exploratory mode, to an exploitation or development mode, or late-stage declining harvest situation, the reserve audit team must recognize the amount of data and information available and the potential infancy or maturity of a property. The quality of technical rigor should be considered more heavily in the reserve audit process. A higher degree of knowledge and intimacy with the property is derived from an approach that spans several years. Just as a financial auditor does not want to see discrepancies and wishes to see everything in order according to standard accounting practices, the reserve auditor wishes to find the same thing. He or she is less inclined to support a seismic interpretation if the horizons do not even track reflective events, and yes this does actually happen. Is the geophysicist following the correct event for the producing formation? Is the interpretation time rendered or a result of a pre-stack depth migration interpretation? Has the interpretation evolved beyond a structural interpretation into a stratigraphic one where reservoir properties can be predicted and if so with what certainty? The last question represents where geophysics, through the use of seismic data to depict reservoir properties such as thickness, porosity, lithology, pore fluid content, compartmentalization due to faulting, sweep efficiency and the like, can possibly make a significant contribution.

Perspective

Professionals cast in the role of being a member of a reserve audit team must be conscious of their professional status and be responsible to the public. These individuals see a lot of plays and properties over the years in their careers. They can quickly sort out what plays or properties constitute great investment opportunities. Conversely, they can assess which clients believe they have a great opportunity when in fact they may not. Reserve auditors can add value to an organization by recommending future work or practices that would permit them to recognize and thereby add value to the corporation should the resultant data so support such a claim. A geophysicist with their seismic data can play a larger role in this process. It is our challenge to demonstrate how the geophysical discipline can be used to assess further recognition of reserves and net asset value.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article