Introduction

A dominant theme during the last decade has been, and continues to be, the issue of globalisation. Globalisation encapsulates a description of a rapid, and pervasive, diffusion around the world of production, consumption, investment and trade flows in goods, services, capital and technology.

Globalisation has yielded such significant, though often controversial, worldwide trends as privatisation and free trade agreements. In addition, it has increased access by oil and gas countries to exploration and development rights, especially in the developing world. Even countries such as Cuba, who maintain a highly centralised Communist system, acknowledge the need for investment and are opening acreage to outsiders. Coupled with the increase in exploration acreage is a decline in many countries of ‘government take’, or the percentage that a government earns of gross revenues less investment and operating costs - making it more attractive for foreign firms.

In Canada, conventional oil and gas reserves have declined over the last ten years. Over the same period, production levels have been steadily increasing while prices have remained relatively stagnant, with the exception of the very recent past. This has further encouraged Canadian firms to explore abroad. As a result, increasing numbers of energy sector professionals are experiencing some period of living and working abroad. Their responsibilities invariably include some element of technology transfer as a direct consequence of the terms stipulated in production sharing agreements. Not surprising, developing countries wish to ensure that local talent is developed.

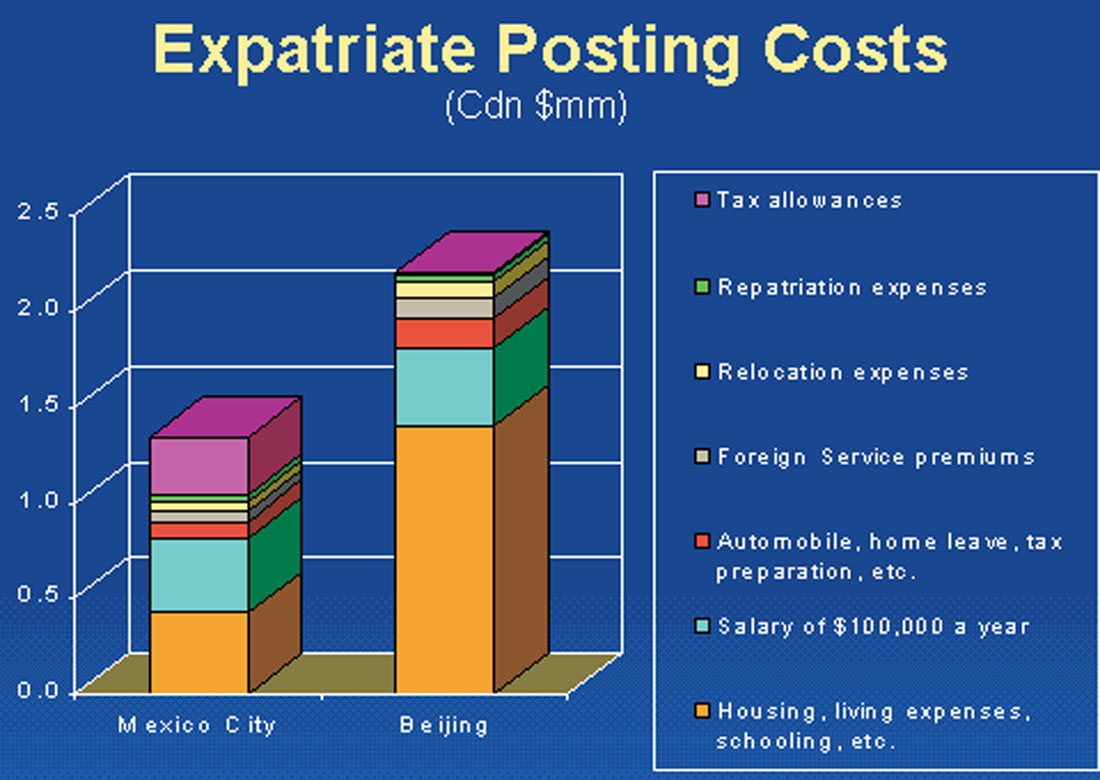

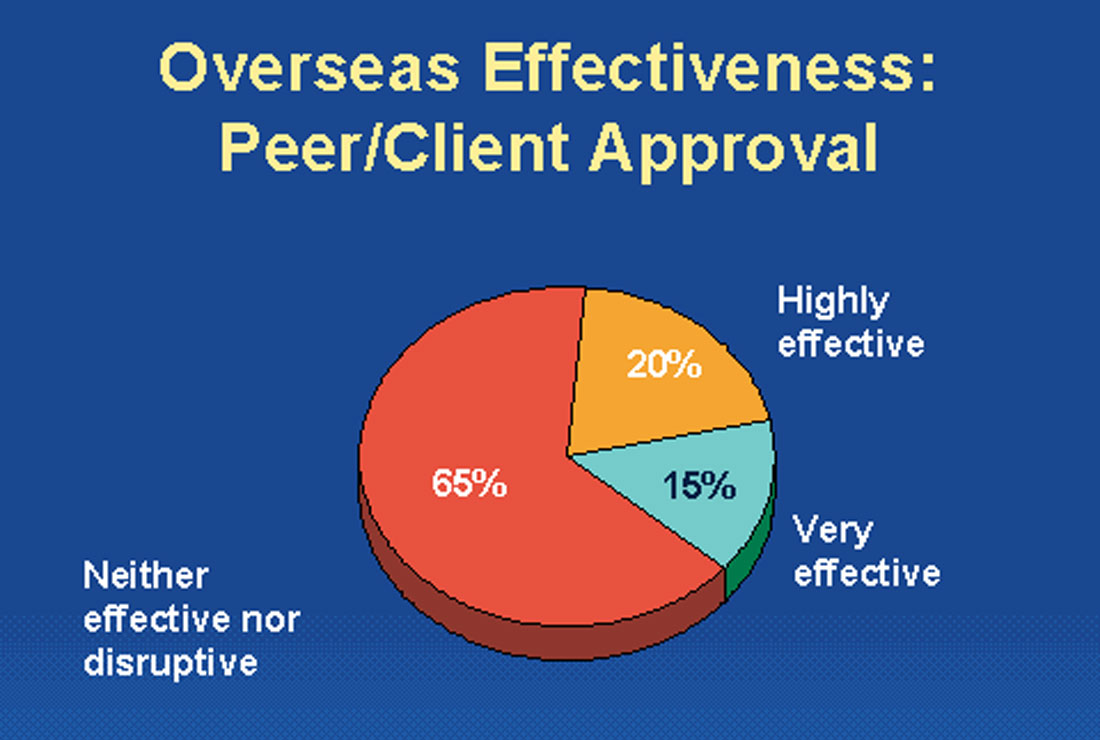

The cost of expatriate assignments is commonly in the millions of dollars (Fig. 1). At the same time, only about 20 per cent of participants in one major Canadian study were rated as being highly effective in the overseas environment (Fig. 2). As a result, Canadian firms are seriously compromising their ability to provide a satisfactory rate of return on their investments. Furthermore, they are demonstrably losing lucrative opportunities and are fueling shareholder dissatisfaction. This has led to a difficulty to raise further, much needed, funds in the highly competitive and fluid capital markets.

Defining Overseas Effectiveness

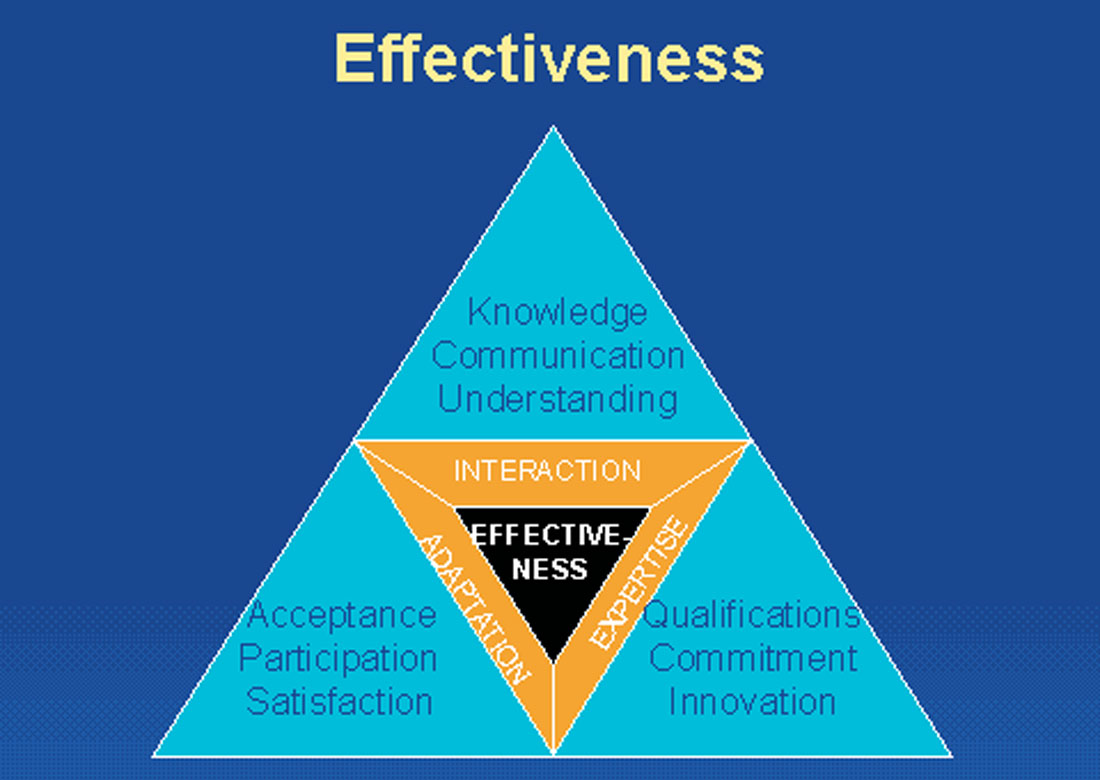

Overseas effectiveness comprises three elements: professional expertise, adaptation and intercultural interaction (Fig. 3). Much of the explanation for the high level of expatriate failure lies in poor selection practices and improper preparation.

Traditionally, an individual’s skills in a specific technical area has been the primary concern to staff screening potential expatriates. But expertise includes more than just an individual’s own training and work experience; it also includes his/her ability to assess the technical capabilities of the overseas job situation and to be innovative.

A number of personality characteristics are associated with success in living and working overseas including empathy, interest in the local culture, flexibility, tolerance, initiative, open-mindedness, sociability, and positive self-image. These characteristics need to be screened for during recruitment and selection.

Furthermore, there are many factors which impact upon an expatriate’s effectiveness. These include: previous overseas experience, age, gender, family situation, language ability, nationality, motivation, attitudes and expectation, culture shock, and personality versus situational determinants.

The Role of Previous Overseas Experience

While previous experience abroad does ease the adjustment to a new country, it does not predict effectiveness in the new environment. Since most individuals are chosen for work, in part, on the basis of previous overseas experience, the implications for recruitment are obvious. Individuals with no previous overseas experience but with requisite capabilities must also be chosen to work overseas. Lack of experience abroad is an insufficient reason to exclude them.

The Age Factor

No direct relationship appears to exist between the age of an expatriate and his or her effectiveness. However, there is a greater degree of altruistic motivation among older individuals and, in the case of developing countries, where Canadians are more likely to be exploring, this attitude does appear to be positively correlated to effectiveness. This altruistic motivation imparts an enthusiasm which can assist an individual through the adaptation to the new environment.

The Role of Women

Some research suggests that women in certain overseas positions and cultures are likely to be more effective than men. In these cases, women exhibit a greater willingness to involve themselves in the new culture and to learn the new language. If these traits are essential to the success of an assignment, then greater consideration should be given to women as expatriates. Of course, many men share these traits and, it would appear, are equally likely to be excluded from such opportunities.

The Role of the Family

A close family is likely to be supportive of the individual members and therefore assist in the adaptation process. However, a family experiencing difficulties prior to departure is likely to see these difficulties exacerbated upon entry into a new culture. Research suggests that singles participate in the local culture to a greater degree than couples with children. This may be due to the fact that family ties reduce contact with the local culture1.

The Role of Motivation, Attitudes and Expectations

The role of motivation is central to overseas effectiveness. Individuals who are committed to the work they are doing are most likely to participate in the local culture. These individuals are seen to be the most effective overseas.

Culture Shock and Effectiveness

Interestingly, individuals most likely to succeed in an expatriate posting are also likely to endure the greatest degree of ‘acculturative stress’, or ‘culture shock’. Individuals with well developed inter-personal skills value other people in their lives. It does not seem surprising, therefore, that these individuals should suffer considerable culture shock when they have not yet established close relationships.

Admitting to feelings of culture shock appears to be viewed, by many, as a sign of weakness. Once again, since technical capability and previous overseas experience are the most valued selection criteria, this attitude does not seem surprising. Other equally or more important characteristics are often ignored.

Personality versus Situational Determinants of Success

Factors such as living conditions and job constraints are described as situational determinants. It has traditionally been felt that these forces have considerable influence on expatriate effectiveness. Recent studies, however, suggest that this is not the case. Similar situations may, in fact, be viewed quite differently by different individuals. Indeed, it is these differences in outlook that have a far more direct impact on the outcome of an expatriate assignment than the actual situations themselves.

Conclusions and Recommendations

An individual who possesses professional, personal and interpersonal skills is more likely to become involved in the local culture. This involvement lends itself to a greater understanding, trust and respect between the expatriate and nationals which, in turn, contributes to an environment where sharing and learning are encouraged.

Recommended solutions for the recruitment of appropriate personnel involve the following areas:

- Self-selection

- Selection

- Preparation

- Interpersonal and Intercultural Communication

Self-selection

The potential overseas worker needs to be aware of his or her motivations for accepting an overseas posting. The objectives which organizations seek to fulfill and the skills and motivations of the potential recruit must be compatible. Hence, there must be an open dialogue between the recruit and the recruiters.

Where the recruit is unaware of his or motivations, methods exist which can penetrate these barriers to attitudes and motives - none of which require the use of force!

Selection

Non-technical criteria need to be given more weight than they are at present. Recruiters must also be very carefully selected and trained. Furthermore, it is absurd that individuals who have no overseas experience should have, as is so often the case, the sole responsibility to recruit. Lastly, skill in achieving rapport, questioning approaches, prompting and probing is crucial in interviewing the potential recruit.

Preparation

While we can identify those recruits most likely to succeed, preparation and training of these individuals is still an area requiring greater consideration. Furthermore, culture shock must be seen as a natural consequence of the stress of a new environment. It should not be ignored nor penalised. It should be responded to with sensitivity and proper counseling. Language training is significant in effectiveness and should be given considerable emphasis.

Interpersonal and Intercultural Communication

It is the inability to encourage and support both interpersonal and intercultural communication that is at the heart of a great many expatriate program failures. It is important that these obstacles be overcome but it is even more important that they be addressed at the recruitment stage. Clearly, not everyone is well suited for this type of work.

At this point, it is worthwhile considering the comments of the ex-Chairman and CEO of Heineken, Gerard van Schaik2, in regards to the recruitment of individuals destined for the ‘international business circuit’:

In the recruitment stage in Heineken, we considered a number of things essential for the ‘international candidate’, such as:

a feel and a genuine interest in other cultures;

ability to adapt to life in a new environment;

command of more than one foreign language or a willingness to learn;

healthy family situation;

purposeful attitude but diplomatic and practical in stressful situations;

On the basis of my experience, a top professional with attitudinal weaknesses in the international environment will be a far bigger risk to the Company he works for than an average professional who has a feel for things.

Recruitment processes need to be aligned with the significant demands of overseas assignments. Furthermore, appropriate preparation and training are a necessary requirement for firms who wish to succeed in the highly competitive overseas environment. They are also essential for those who wish to include such assignments in their career portfolio.

Without a serious consideration of these issues, Canadian firms can expect to perform as poorly as one Canadian firm active overseas. In a recent overseas venture, this firm lost Cdn $1 million on revenues of only Cdn $6 million. It was employing the best Canadian technology, second to none in the world. It had highly technically skilled professionals leading the effort. Unfortunately, it did not appreciate the cultural challenges of working overseas.

The difficulties of succeeding overseas are many, if not profound. Still, these difficulties are not insurmountable.

The difficulties of succeeding overseas are many, if not profound. Still, these difficulties are not insurmountable.

1 Having worked in Buenos Aires, Argentina as a single, Spanish speaking male, the author found that practice conformed wonderfully well to theory in this case. The cross correlation was fun!

2 Personal communication

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article