Some time ago the RECORDER published an article of mine (December 2000, Odyssey of Oil). That article took a look at some ancient oil industries from around the world, and drew parallels between those ancient industries and our modern oil industry. Readers of that article would have detected in the theme an axe that I like to grind. I find that human cultures have a tendency to exaggerate their own achievements, be it in the fields of arts, science, business or technology, and downplay, denigrate or downright dismiss those of other cultures. As a teenager I remember feeling outraged at Erich von Daniken’s ludicrous conclusion that only the assistance of some superior extraterrestrial beings could explain the glorious achievements of now extinct cultures around the world. As a member of our Euro-North American western culture, I feel we’re particularly guilty of relegating other cultures’ achievements to also-ran status.

Subsequent to writing that article I happened to read an excellent book with the title Salt: A World History, written by Mark Kurlansky. I highly recommend it to anyone with an interest in history and human affairs, along with Kurlansky’s other books, Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, and The Basque History of the World. The three books’ themes are interrelated in a most entertaining way. But to get back to Salt, in one chapter an ancient salt producing industry involving sophisticated drilling techniques and coproduction of brine and natural gas in China’s Sichuan province, far pre-dating western efforts, is detailed. I was tremendously interested by this, and immediately felt that this topic would make a great follow up to my first one, as it involved hydrocarbon exploitation, and better still, was ideal nourishment for the bee in my bonnet – it involved another culture, from long ago, whose exploits and achievements are frequently overlooked by us in the west.

Through a little research I discovered the existence of a museum dedicated to Sichuan’s ancient brine / salt / gas industry. Called The Salt Museum, it is located in Zigong City, named after two of its famous salt wells, about three hours’ drive south of the provincial capital Chengdu (figure 1). I resigned myself to the fact that it was highly unlikely I’d be close to China in the near future, let alone Zigong. Then earlier this year, out of the blue, a business-related trip to Chengdu materialized, and I was determined to visit The Salt Museum while over there. It all worked out, and this article is the result. My aim is to provide interested readers with an understanding of the fascinating achievements of these people hundreds of years ago. As with my previous article this is not a scholarly analysis, but rather an amateur’s efforts to share his enthusiasm, and provide entertaining and stimulating reading.

When a break in our work responsibilities allowed it, I and my Geo-X colleagues, Bo Li and Andrew Royle, set off to Zigong, with our generous and gracious hosts from the Sichuan Geophysical Company (S.G.C.), Gang Lin and Zhirong Li. To drive through rural Sichuan is interesting, as one gets a sense of the intensity of human development in one of China’s richest regions. The heavily populated portion of Sichuan is a large basin, flanked by the Himalayan Plateau to the west, the Long Men Mountains to the north, and the Hua Ying Mountains to the south. The Yangtze River flows along the southern edge of the basin, and numerous tributaries drain south through the rich agricultural lands and into the Yangtze . With its fertile, well watered soil, and mild climate, Sichuan is one of China’s most productive farming regions. Since ancient times, Sichuan has been called “heaven country” within China. The most common crops include wheat, canola, rice, cotton, barley, corn, yams, tobacco, fruits and vegetables. On higher, less fertile ground, huge areas are devoted to the cultivation of mulberry bushes (figure 2), which feed one of the world’s oldest and biggest silk producing industries.

Naturally, with such attractive conditions for human habitation, Sichuan has been occupied by humans since the early dawn of our existence. The countryside has been worked by the human hand for so long, that it is hard to spot a single wild area in the basin proper. Even steep hillsides are terraced for farming, and ancient family crypts hewn into rock cliff outcrops can be spotted frequently from the highway. The contrast between the luxury cars speeding along the modern 6-lane highways, and the ancient terraces, tombs and irrigation systems is startling, but one can easily imagine one long continuous evolution of human technology here, from thousands and thousands of years ago, to the present. Many of China’s ancient technical accomplishments came from this region, including sophisticated irrigation techniques, and what I am particularly interested in, their drilling technology.

My reaction on arriving in Zigong was typical for a westerner first visiting China – yet another city of, what - half a million, one, two million people? - that I had never heard of, with big boulevards, high buildings, people everywhere, construction cranes sprouting willy-nilly. The scale of development in modern China is simply staggering.

After a visit to Zigong’s Dinosaur Museum, on par with our Tyrell Museum in Drumheller, and the requisite banquet of incredibly delicious Sichuan food, we arrived at the Salt Museum. The museum is housed in the former Shanxi Guildhall, built in 1736–1752 AD by salt merchants from Shanxi Province to the north (figure 3). The museum and the building housing it easily exceeded my expectations, as this is truly a world class exhibition. The fact that this historical building and the museum itself are still in existence today can be largely attributed to patriarchal leader Mr. Deng Xiaoping, who proposed and promoted this museum in the 1950s.

The earliest evidence of wells in China, in Zhejiang Province, comes from the era when humans were first turning to agriculture in this region, some 7,000 years ago. Approximately 5,000 years ago Chinese coastal people were boiling sea water to produce salt. As high density human settlement penetrated further and further inland and increasingly relied on farming, salt, critical to human survival as a vital food supplement and preservative, became a valuable commodity. The first recorded salt well in China was dug in Sichuan Province, around 2,250 years ago. This was the first time water well technology was applied successfully to the exploitation of salt, and marked the beginning of Sichuan’s salt drilling industry. From that point on, wells in Sichuan have penetrated the earth to tap into brine aquifers, essentially ground water with a salinity of over 50g/l. The water is then evaporated using a heat source, leaving the salt behind.

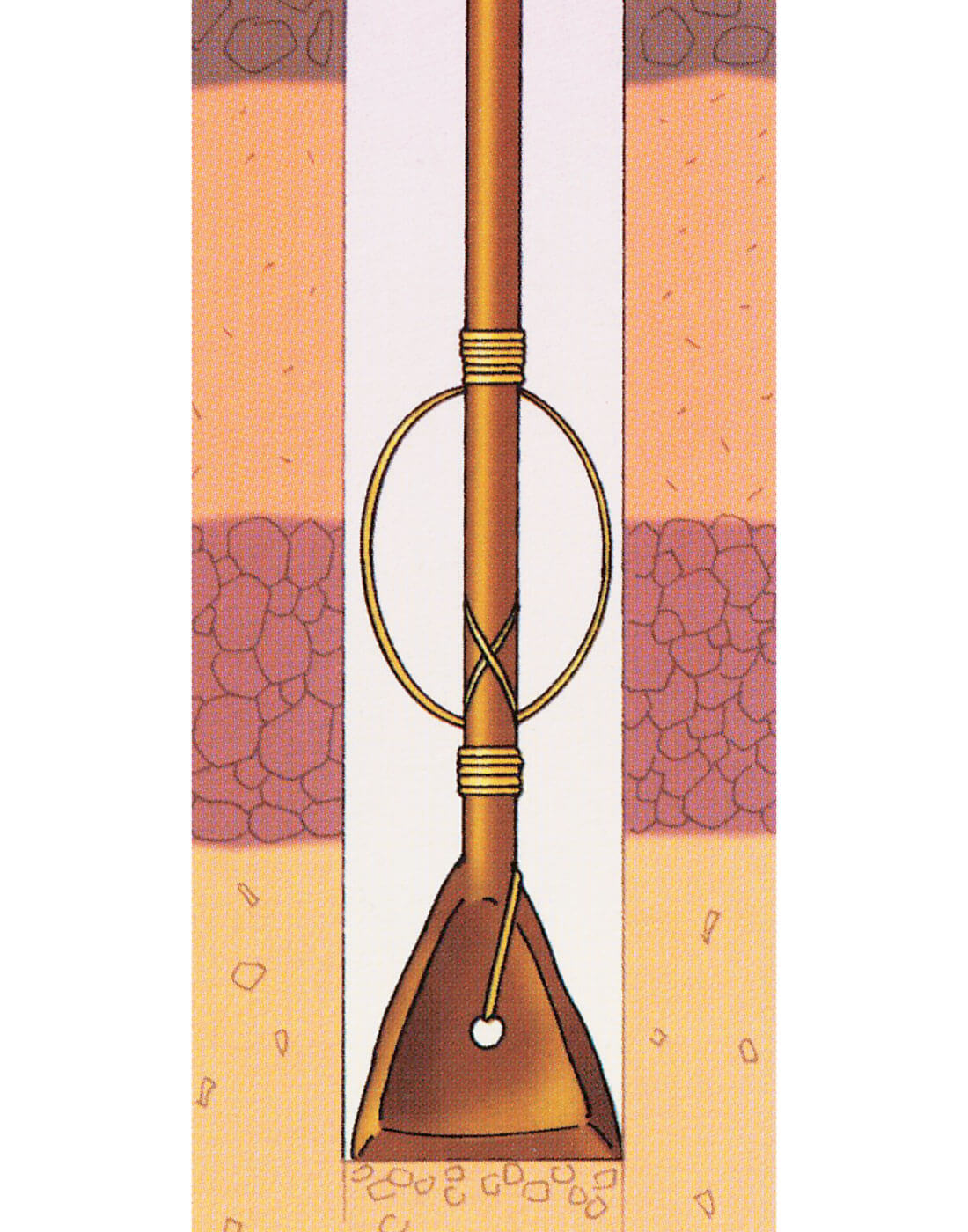

At some point around 2,000 years ago the leap from hand and shovel dug wells to percussively drilled ones was made (figure 4). By the beginning of the 3rd century AD, wells were being drilled up to 140m deep. The drilling technique used can still be seen in China today, when rural farmers drill water wells. The drill bit is made of iron, the pipe bamboo. The rig is constructed from bamboo; one or more men stands on a wooden plank lever, much like a seesaw, and this lifts up the drill stem a metre or so. The pipe is allowed to drop, and the drill bit crashes down into the rock, pulverizing it. Inch by inch, month by month, the drilling slowly progresses. It has been speculated that percussive drilling was derived from the pounding of rice into rice flour. When I read of this technique in Salt, I imagined a fairly crude technology. I had no idea how sophisticated these drilling methods became, to the point where these people really had developed most of the tools and techniques one might see on a modern drilling rig, albeit on a smaller scale and without the benefits of modern machining methods.

(from Zhong & Huang)

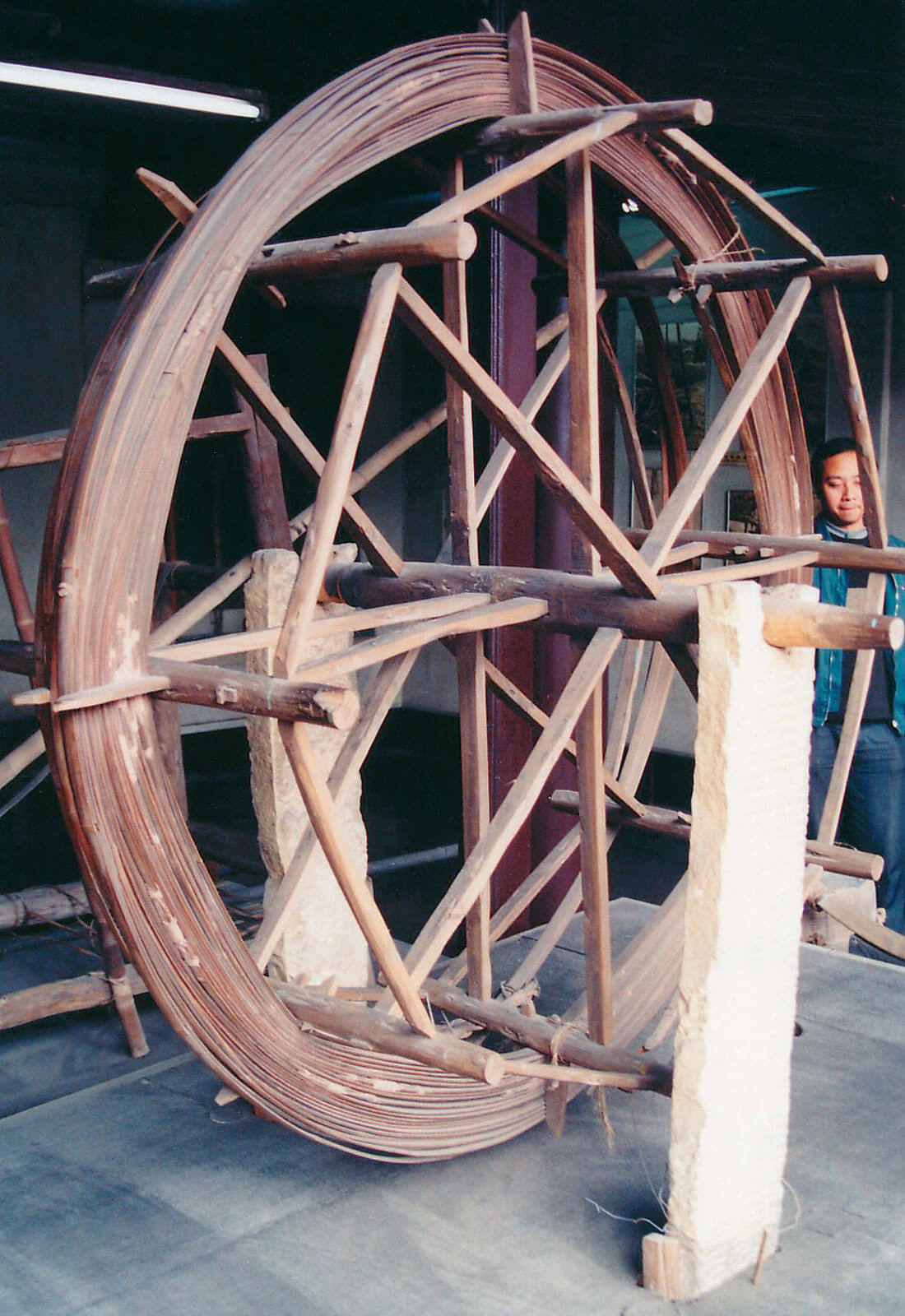

At regular intervals in the drilling, the crushed rock and mud at the bottom of the hole needed to be removed. The drill stem would be pulled from the hole using a large wheel, somewhat similar in appearance to that on a modern flexible cable down hole tool truck. A length of hollow bamboo with a leather foot valve would then be lowered to the bottom of the hole. When the tube was lifted, the weight of the mud inside would keep the valve closed, and the contents could be brought to the surface. Drilling would then recommence.

(from Zhong & Huang)

The drilling method on its own is impressive, especially when considering that the rest of the world had nothing comparable in the earlier centuries. But even more impressive are all the techniques the Sichuan drillers developed to overcome common drilling problems – cave ins, lost tools, deviated wells, and so on (figures 5 & 6). A huge variety of tools and techniques evolved to handle well repair issues (figure 7). Many different drill bits were also developed, with different sizes, shapes and compositions, to deal with the different rock types encountered, and the many different drilling requirements. For example, opening the hole at the wellhead required a large heavy bit (3m long, 150-250 Kg) called the “Fish Tail” (figure 8); the “Silver Ingot” drilled the well bore rapidly, but roughly; the “Horseshoe” bit drilled slowly, but achieved round, smooth, high quality well bores. Hollow logs were used in the near surface as casing.

(from Zhong & Huang)

(from Zhong & Huang)

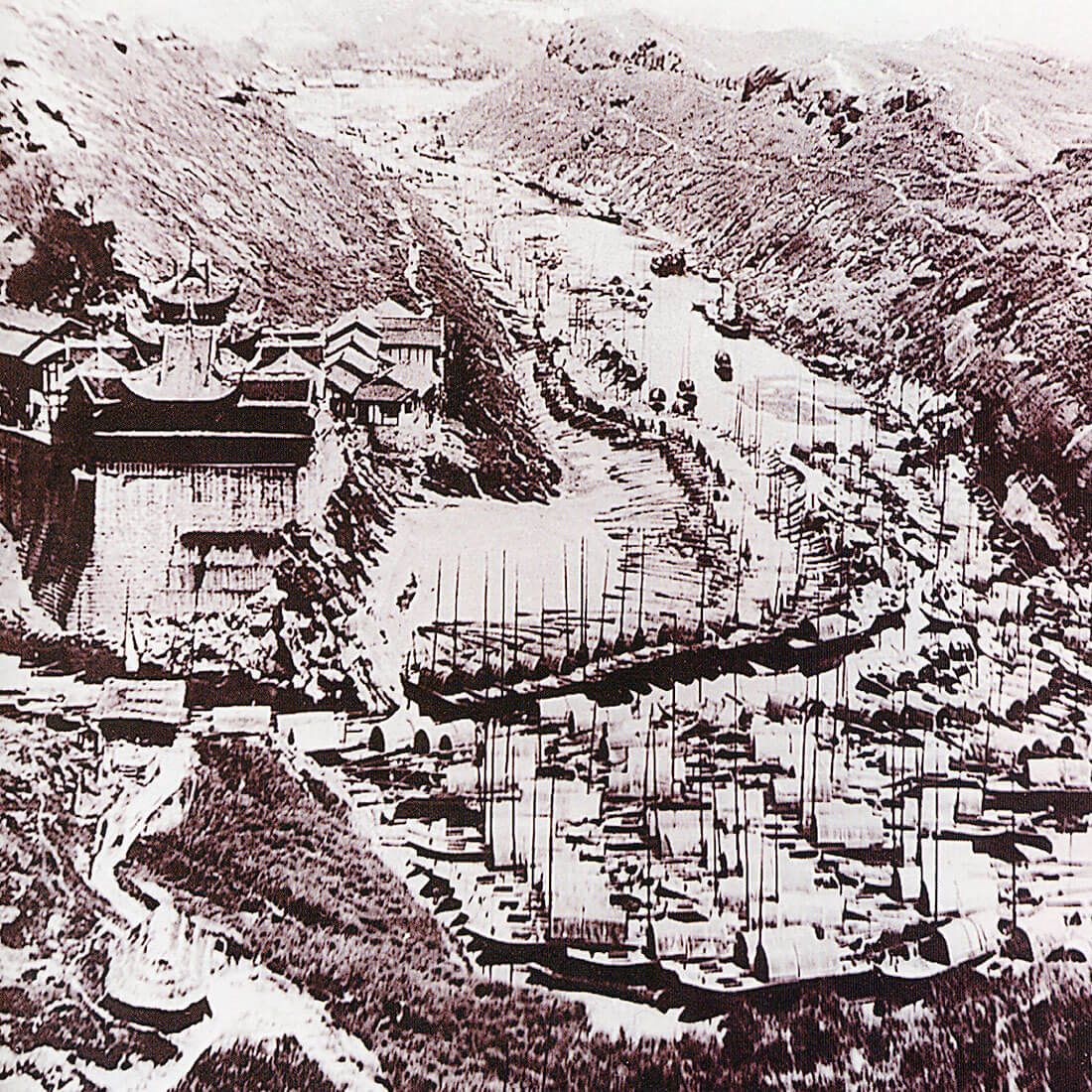

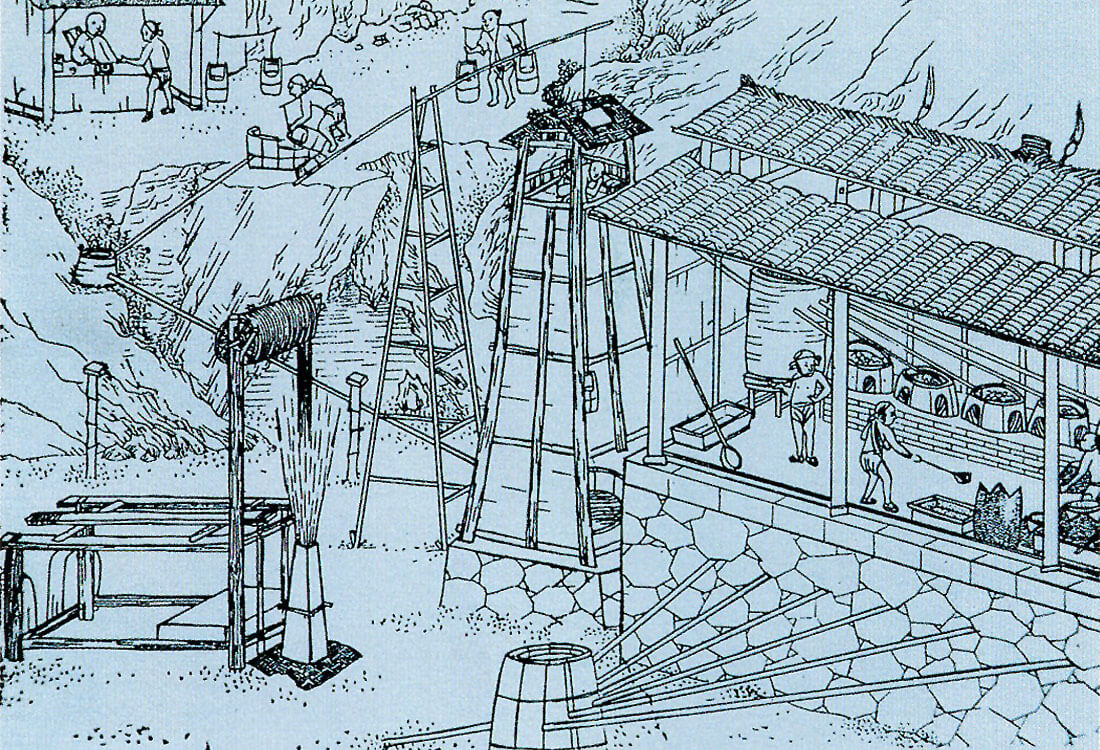

A major breakthrough was achieved around 1050 AD, allowing deeper wells, when solid bamboo pipe was replaced by thin, light, flexible bamboo “cable” (figure 9). This dramatically lowered the weight that needed to be lifted from the surface, a weight that increased with the depth being drilled. By the 1700s Sichuan wells were typically in the range of 300 – 400m deep, and in 1835 the Shenghai Well was the first well in the world to exceed 1,000 metres of depth. In comparison, the deepest wells in the U.S. at that time were about 500m deep. The Sichuan salt producing industry was centred around Zigong, and early photographs show hundreds of producing derricks (“heaven carts”; figure 10), salt stove operations, and the Fuxi River jammed with salt trading boats (figure 11). Brine and natural gas were transported through 100s of kilometres of bamboo pipeline (figure 12).

The fuel used initially in the evaporation process was of course wood. Sources of wood became scarce due to the scale of the salt production industry. Some energy saving techniques were used during evaporation: spreading the brine on tree branches under the sun to increase the salt concentration before boiling, and putting several boiling pans on the same chimney path to use residual heat. There are instances of oil and gas production and use in China going back as far as 61 BC, but it appears as if the salt and hydrocarbon industries were separate for a long time. Fortuitously, at some point in the 16th century, techniques to harness the natural gas encountered during drilling for brine were developed, and this allowed natural gas to be burned beneath the big salt pans. It was the coexistence of brine and gas that pushed Zigong’s salt production into the industrial scale. Once wells were able to reach down to 700-800m, they were able to produce both brine and gas from the Jialingjiang group Triassic formations. Annual salt production in Zigong in the 1850s was about 150,000 tons. The Chinese population was about 0.45 billion at that time. The salt industry was a huge economic driver, and many large cities in Sichuan were established, and flourished, because of the lucrative salt trade.

(from Zhong & Huang)

A key technological advance was the introduction of the “Kang Pen” drum at the end of the 18th century (figure 13). This drum sat on top of the wellhead, and the pressure within the drum was controlled such that gas and brine could simultaneously be produced, and efficiently separated. One bamboo pipe line would take away the brine, and others the gas. The 2,000 year plus Sichuan salt industry has drilled approximately 130,000 brine and gas wells, and 10% of those were in the immediate Zigong area. Zigong has a cumulative gas production over this period of over 30 billion cubic metres. The area continues to be a major salt producer, and many of the historical wells are still in production.

(from Zhong & Huang)

One minor detail I found interesting. When I had first read of bamboo pipelines, I wondered how the barriers separating the segments within the bamboo were dealt with. Did they drill holes through these compartment walls with long augur bits to create pipe? My curiosity was satisfied by one of the displays depicting the process of turning bamboo into pipe. Each length of bamboo was cut in half, down its length. The segment walls were removed, and the insides of the bamboo further hollowed out to create a smooth inside surface of constant interior diameter. The two sections were then put back together and bonded with a glue made from a mixture of lime and tree seed oil. It was further bound together with twine inset into grooves in the outside surface of the bamboo, to prevent fraying, especially for down hole use where the hole’s rock walls would scrape against the exterior surface of the bamboo pipe as it was repeatedly lifted and lowered during drilling and production operations. Similar glue and twine techniques were used to link and splice pipe line sections together end-to-end in an airtight fashion. As recently as the 1950s there was still over 95km of bamboo pipeline in operation in the Zigong area.

(from Zhong & Huang)

Being earth scientists, Andrew, Bo and I were naturally curious about the geology of the region, and the knowledge the ancient drillers had of the subsurface. Did they practice geology, or geophysics, in some form? Did they draw diagrams of the sub-surface and choose new drilling locations based on geological models? This is one area the museum displays do not touch on. However, it is known that well locations were chosen based on the distribution of existing gas and brine wells, and on a variety of surface clues. Brine and gas seeps were obvious indicators of a good location. The salt drillers looked for a salt “frosting” on the surface rocks, or the smell of brine. Yellow brine wells (high in ferric chloride) were usually drilled into yellow sandstone outcrops, while black brine wells (containing hydrogen sulfide) were drilled into cracked sandstones with a black crust. Brine only wells were usually drilled on hillsides, while gas producing wells were usually drilled on hilltops, suggesting that the topography reflected the underlying geological structures. However, surface clues would not have revealed much about targets down towards 1000m depth, so we’re left to speculate on whether geological skills advanced along with the drilling technology.

My brief visit to Sichuan left me intrigued, fascinated, and eager to learn more about China’s ancient technical accomplishments. I can highly recommend the region as a place to visit, not only for its interesting historical sites, but also for its natural beauty (most of Sichuan is mountainous and unpopulated, especially the west, with bamboo forests, and panda bears), its rich culture with many interesting ethnic minorities, its delicious food, great shopping, and its wonderful, friendly people. However, the highlight of my trip was the visit to the Salt Museum, and I hope I have passed on my enthusiasm for this topic to readers.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article