Bill Sydorko has progressed from working on geophysical crews of four or five men in 1950 to supervising crews of up to 30 men during the 1980s and 90s. Where 16 or 24 traces per seismic record were once standard, now he routinely deals with a minimum of 144 per record, and sometimes as many as 1,000. He has ridden horses and zipped about in helicopters to lay cable and set out geophones. He has watched seismic records evolve from photographic images on paper to highly sophisticated computer output. For Bill Sydorko, change has been an ever-present companion, but during his 45 years in the field, he has successfully met the myriad challenges change has presented. The unwavering constants, in the midst of the incredible technological advancements swirling about him, have always been the energy and commitment that reside firmly entrenched at the core of his deeply ingrained work ethic.

At 69, Sydorko is thinking the time is approaching when he will have to seriously consider retirement, but says he isn't exactly looking forward to it. "It's important to keep busy," Sydorko says. "I guess eventually a person has to decide that enough is enough, and I guess I will too, but I'm not sure what I'll do then. As long as there's work to do, I'll keep doing it."

Entering the 46th year of a career spent entirely in the field, except for a single month of office work in the late 1960s, is unusual in itself, but what makes Sydorko's accomplishments even more unique is that getting out and doing seismic field work is still, after all this time, a joy. "It keeps me young," he says.

And just in case the field work doesn't keep him young enough, Sydorko stays in shape by taking long walks whenever he gets the chance. Garnet Mueller, Vice-President of JRS Exploration and a long-time friend of Sydorko's, says he recently called Sydorko one evening about 8 p.m. "Bill's wife said he had just gone out for a walk, so I said I would call him when he got back. She said, 'Well, fine, that'll be about midnight or one.' "

Sydorko's belief in the benefits of fresh air and exercise is a reflection of his deep prairie roots. Although he was born in Lac du Bonnet, Manitoba, in 1926, Sydorko spent all of his early years on his father's homestead near Whitelaw, Alberta. He started working with Farney Exploration in December, 1949, when Canaruan geophysical activity constituted almost 10 per cent of the world's total, and when the Canadian Society of Exploration Geophysicists was newly born. Farney was later bought out by Independent Exploration, and eventually became Teledyne Exploration, part of the giant Teledyne Inc.

By the early 1950s, Canada had moved into second place worldwide in terms of geophysical activity, and Sydorko had already gained a reputation as the most sought-after shooter on Farney's payroll. Garnet Mueller was an operator on the same field crew as the 5' 11" Sydorko back in 1954. "Being a shooter required skill and physical stamina," Mueller says. "We used big charges in those days. Drill holes were anywhere between 90 and 250 ft. deep, and they would have to be loaded with about 50 Ibs. of dynamite. Bill is a big guy, and he produced five times as much work as anyone else. First he'd learn to do whatever it was he had to do. Then he'd learn to do it faster and better than anyone else."

One of Sydorko's fondest memories of those early days is a job he was on at Loon Lake, in the Red Earth area of northern Alberta, where the crew lived in tents and used 21 horses to pack all the gear and instrumentation. "We had a wrangler to handle the horses and the wrangler's wife was the cook," Sydorko says. "We would work all day, drilling our holes about 15 ft. deep with a posthole auger. We'd take a shot. then load everything up on the horses and move up to where we wanted to set up the next shot."

Sydorko and his crew were at Loon Lake for 52 days. Working three to four months in those days was not uncommon, but today crews are seldom out for more than a month at a time, and working conditions are much better than they were in the 1950s.

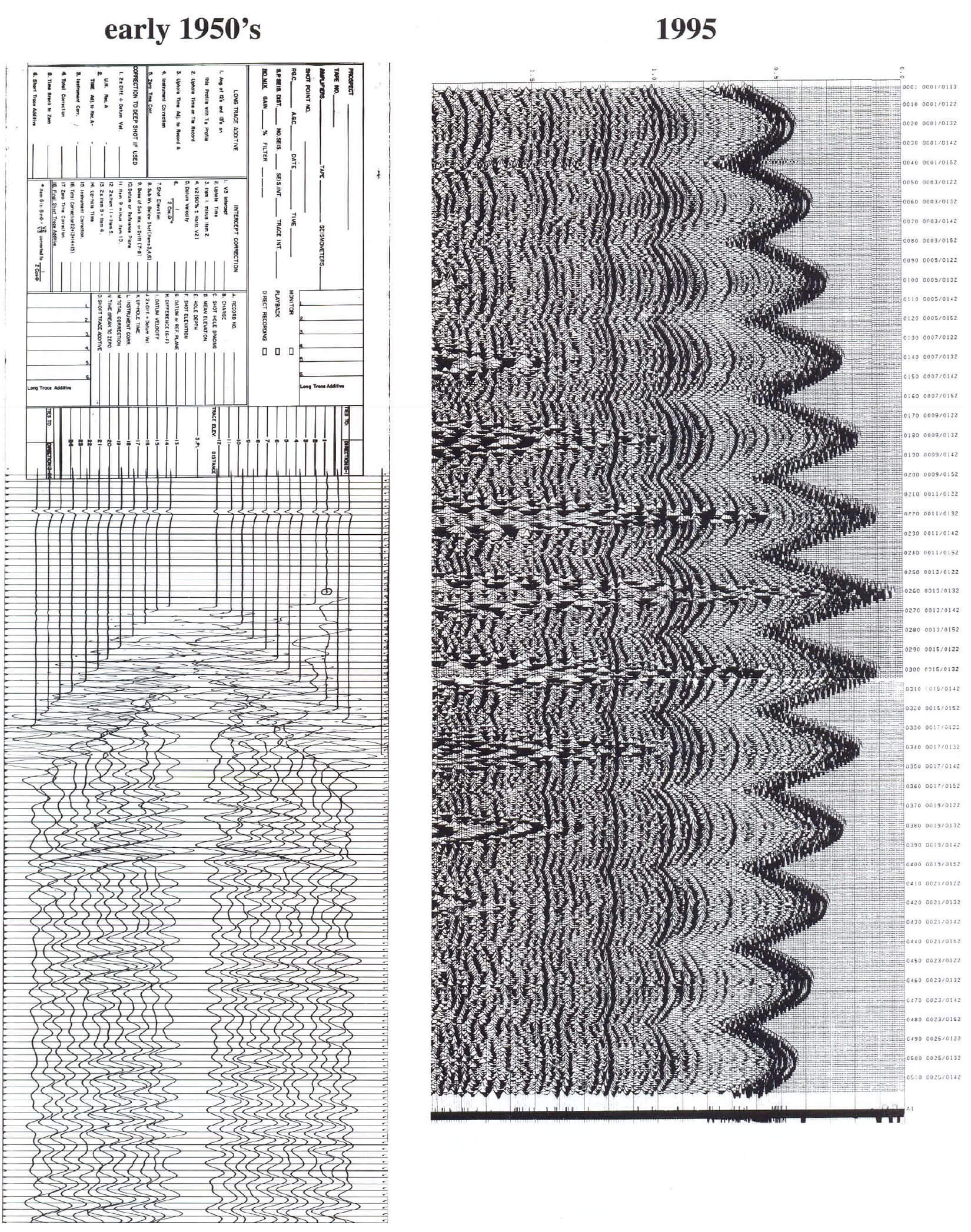

Sydorko remembers that in those times, each of the 24 traces required three geophones, and each crew required three trucks. "These days there are 120 traces or more, each with six to nine geophones, and each crew has seven trucks," Sydorko says. "As far as instrumentation went, in those days there was no tape - if I missed a shot, I had to reshoot. And the geophysicists had to take all the information off a paper record. Now everything is on digital tape. In the field, we used to spend our slack time picking first breaks manually."

In 1951, Sydorko married Mary Zayorkowski, who had come to work at her uncle's hotel in Bluesky, Alberta, in 1948. Twelve days after the wedding, Sydorko left for a 44-day work stint in the bush. But in the summers that followed, the Sydorkos moved together, packing their belongings in suitcases and boxes, searching out accommodation in whatever town or village was closest to Bill's worksite and living on his salary of $250 a month. One hot and dusty year the young couple, who by then had had their first child, boarded with a farm family near Kelvington, Sask. During the long days when Sydorko was away at work, Mary says she kept busy caring for their child. "I didn't mind it a bit," she says. "We were young and didn't know any better."

In 1954, while Mary kept the home fires burning, Sydorko and Mueller were busy doing the latest thing in seismic field work. "If we wanted to look at a particular section, we'd shoot all the corners, and then take a shot in the centre," Mueller says. "That was what was called a five-point correlation. We'd shoot it with 12 traces. It was real scratch-the-surface reconnaissance work."

Between 1954 and 1956, technology in the geophysical industry moved ahead at an incredible pace, but Sydorko took it all in stride. The development of heavy load-bearing tracked vehicles called Nodwells made work in remote areas possible. Sydorko says the Nodwells took him across muskeg and other difficult terrain that would otherwise have been impossible to negotiate. A highlight of 1955 was the first use of helicopters in the industry to carry geophysical prospecting equipment to some remote locations. A few years later, when Sydorko began travelling in helicopters, he found he liked them – they often transformed a three-hour drive to work into a 10-minute jaunt.

But the event that had the most impact on the industry was Texas Instruments' use of transistors, which would make vacuum tubes as extinct as the dinosaurs. The significance of transistor technology to seismic work was that they afforded increased channel capacity, and thus the capability to record over larger areas. Sydorko and several other operators went to the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology for a week-long course in transistor theory. Sydorko says it was just another example of how the industry was moving forward. "For me it was interesting, and technically, it was just another case of going with the flow."

Another major technological advance occurred in 1957, the same year Sydorko moved his family to Calgary so his eldest child could attend school. A company called Canadian Magnetic Reduction Limited became the first Canadian company to begin processing magnetic tapes. A year later saw the advent of Vibroseis technology that utilized a seismic source other than dynamite, and in 1959 the data exchange trade in Canada took off.

Throughout these years, Sydorko continued to apply himself to his field duties with a commitment and work ethic that earned him the respect of all who dealt with him. Bud St. Clair, former president and general manager of Teledyne Exploration, says Sydorko was a perfectionist.

"There was a saying in the company, that if Bill was assigned to a job, no one had to worry, because he would do all the worrying," St. Clair says. "He double-checked everything. He had the best work ethic of anyone I ever worked with. He worked harder than anyone out there in the field. If we could have cloned one person to create the perfect field crew, Bill's the guy we would have picked."

In 1956 in spite of all the double-checking, Sydorko experienced the most bizarre occurrence of his entire career, while conducting a program near Cardston, Alberta, which boasted a school adjacent to a water tower. "We took a shot," Sydorko recalls. "At that moment, there was a big bang and a cloud of dust, and the water tower came down."

Sydorko and his crew were stunned, assuming they were responsible for knocking the water tower down. Horrified, they ran to the school, to discover that the tower was being dismantled. It had come down at the exact moment the seismic crew took its shot. Sydorko says the experience was frightening – since the tower was next to the school, there was fear that someone might have been hurt. "It was the strangest coincidence, that the tower would come down right then," he says.

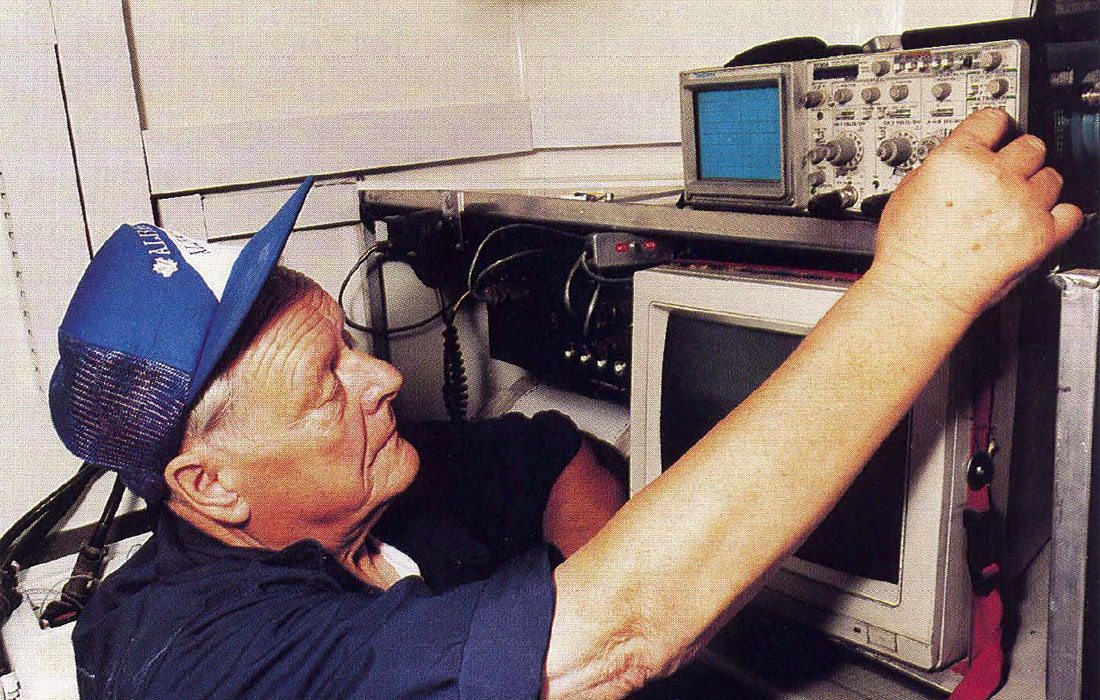

If transistors highlighted seismic industry news of the fifties, the headline technology in the sixties was the replacement in the field of analog recording systems by digital instruments and the introduction of computerized data processing. The big news for Sydorko in 1962 was a promotion from shooter to instrument supervisor, or observer, in the recording truck. St. Clair, for whom Sydorko was working at the time, says he was a natural for such a position. "An observer has to maintain sophisticated electronic gear and supervise the crew laying out the cable and geophones," St. Clair says. "It's the most responsible job in the field. Bill became the best observer we had. He may not have had the technical background, but he had everything else going for him."

An industry milestone was also passed in 1965, when the Petropar Company sent the first seismic crew to the high Arctic. Other companies soon followed, and over the course of the next decade, Sydorko spent seven winters on the delta north of Inuvik and up toward Tuktoyaktuk. "That work was very challenging because of the cold and the dark and the isolation," Sydorko says. "One time we sat for two whole days in the camp at the Dutch Mill airstrip on Ellef Ringnes Island. We couldn't see where to go. We used to keep two days supply of food in the recorder vehicle. There were times I felt scared, but somehow we always found camp. After a while you got used to the conditions."

A challenge of a more humorous nature came to Sydorko during a program in Ontario in 1976. The jug line crew consisted of five young ladies from Goderich, who, unlike their male counterparts, were happy to earn a minimum wage of three dollars an hour, and who were, according to Sydorko, better workers. "This one girl on the jug line was really good, really fast," Sydorko says. "She and I had a race. As it turned out, I won, but you know, I really think she let me win. She was awfully fast. Those girls worked really hard and did a good job. One company had an all-female crew at one time, but you don't see that anymore – I don't know why."

Sydorko continued to work in the field throughout the 1980s, in the midst of continued technological advances. Better surveying equipment, ever-increasing numbers of channels and the advent of three-dimensional surveys transformed seismic data acquisition into a highly technical process. St. Clair says Sydorko had no problem keeping up. "It can be pretty tough on a person with no technological background, but Bill is very intelligent," St. Clair says. "He had both in-house and out-of-house training, and he did well"

Sydorko continued to do well when Norcana Resource Services borrowed him from Teledyne in 1987 to do a 3D survey. In 1989, when Teledyne shut down, Sydorko went to work at various times for Pioneer Exploration, CanGeo Exploration and JRS Exploration before moving to Norcana, where he has been since 1993. Norcana president Jim Irvine says Sydorko represents an important asset in the Norcana organization.

"Bill is a hard worker who is very, very conscious of quality control," Irvine says. "On top of that, he is the kind of guy who gets along with everybody - there isn't anyone here who doesn't get along with him and like him a lot.

"He's also technically very capable. It's incredible how the technology has advanced, and how Bill has advanced right along with it. Not only does he keep up with others, but sometimes they have to work at keeping up with him. He's a mentor for the younger workers. He teaches them proper techniques, and he earns their respect. "

In 1994, at age 68, Sydorko took his first computer course. "It was just a really basic course," he says. "But everything these days is done with a computer. I still prefer working with the DFS Vs. Computers are a little bit intimidating."

As his retirement draws near, Sydorko looks back with pride upon his long field career. Perhaps the greatest reward is the deep sense of satisfaction he experiences as the result of work done well. In his current job with Norcana, Sydorko continues to relish the opportunity to work hard in a rapidly-advancing industry, and to enjoy the excellent health he attributes to an active, outdoor lifestyle. "I like to go out with the young guys and help them hustle jugs," he says. "It's great exercise. Some of them try to outdo me, but I can still keep up with a lot of them."

Lately, Sydorko has been spending time catching rainbow trout in Kananaskis or, in winter, going ice fishing in the Chain Lakes. He also enjoys his grandchildren and one great-grandson. "I spend a lot of time with them," he says. "They're quite the little hellions."

As for the future, Sydorko looks upon his impending retirement with some trepidation, yet feels confident he will be able to find activities that will keep him involved and busy. He says he and Mary will perhaps do some travelling, and that he will keep his eyes open for hobbies that might interest him. What he knows for certain, he says, is that he won't be idle.

"If you stop working at something and let yourself slow down, that's not good," he says. "If you do that you'll just rust away."

The idea of Sydorko rusting away somehow seems highly unlikely.

(Data samples courtesy of Bill Sydorko and Norcana Resource Services [1991] (Ltd.)

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article