During the fall of 2008, the Canadian Federation of Earth Sciences (the “CFES”) issued a report entitled Human Resources Needs in Earth Sciences in Canada. Dubbed Canada’s ‘first-ever,’ multi-sector survey – spanning government agencies, academic institutions, and the petroleum, mining, environmental and geotechnical industries – the report voiced concerns about declining student enrolments, juxtaposed against a greying population of geoscientists across the board, with the exception of the environmental industry, Canada’s fastest growing employment sector. According to the report, the impending demographic crunch and the projected shortage of highly qualified professionals (“HQPs”) could threaten the future viability of Canada’s Earth science sectors.

With a population of about 20,000 Earth scientists nationwide, Canada has a history steeped in mining and oil and gas exploration – the very health of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) hinges upon the sustainable harvesting of the country’s natural resources.

Photo credit: Dr. Elisabeth Kosters, Executive Director, CFES.

The recent global economic turmoil, coupled with a 70 percent decline in world oil prices, however, has forced the oil and gas sector to slash capital expenditures and to reduce workforces.

Ascant six months ago, Calgary-based oil and gas companies were aggressively competing for both entry level and experienced Earth scientists – today, layoffs in the oil and gas sector have translated into an uncertain future for geoscientists. Despite being published during the euphoria of an unprecedented economic boom, the CFES survey provides an historical overview of employment trends, and lays out a road map to bridge the growing capacity gap, addressing human resource needs during the next five years.

According to Canada’s oil and gas industry leaders, the report’s findings are timely – and more relevant than ever – as the industry weathers the current economic storm, navigates uncertain waters, and shifts its business model from exploring for conventional to unconventional resources in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin.

“No one has ever looked at purely Earth sciences across the industrial sectors, at demographics and future trends,” says Ian Young, past president of the CFES and EnCana Corporation’s Vice President, Business Affairs Canadian Foothills. “To me, the results of the survey are even more urgent because we’re experiencing a recession.”

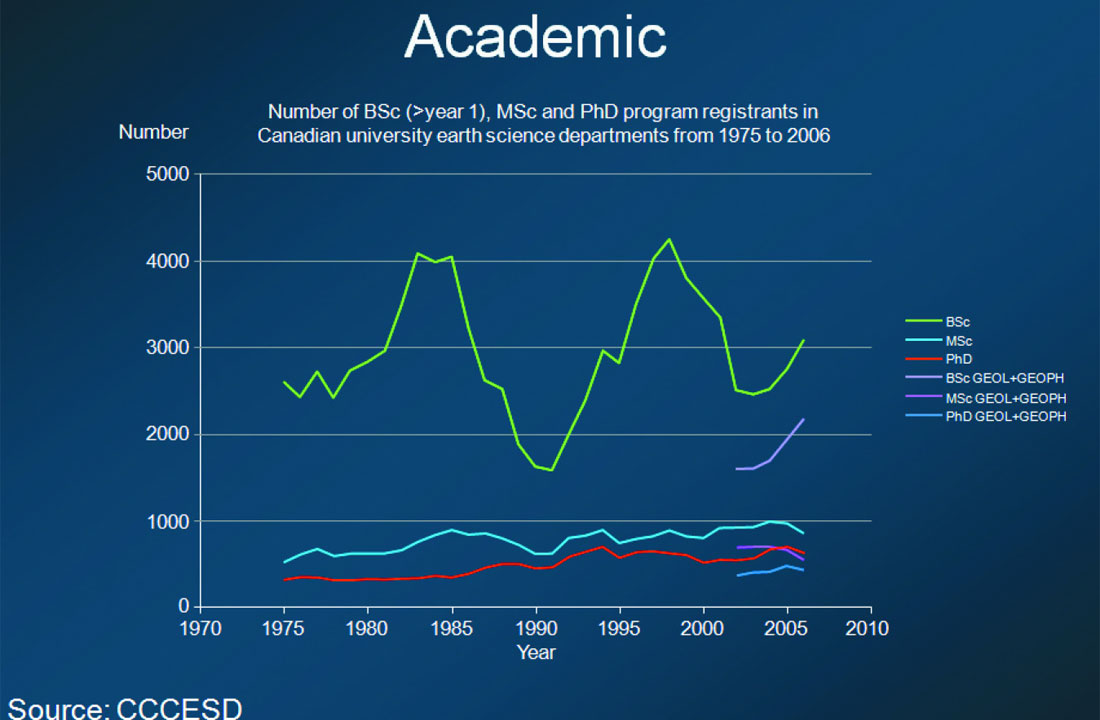

Data collected by the CFES indicate that university enrolment, at the B.Sc. entry level, tracks the boom and bust cycles of commodity prices for metals and oil. Between 1986 and 1999 – tumultuous years for the global oil and gas industry – academic enrolment plummeted in undergraduate Earth science programs. During this same time period, Canada’s oil and gas industry experienced waves of layoffs and dramatically reduced the recruitment of university graduates, resulting in today’s bimodal distribution of new hires and baby boomers. “When the demand side (for oil) picks up again, we’re going to have a worse human resources problem,” cautions Young. “People have described mining and oil and gas as the two solitudes,” he said, pointing to Canada’s traditional employers of Earth scientists. “Hopefully, there’s more work for geoscientists in geotechnical, environmental and mapping applications.”

Photo credit: Dr. Robert Fensome, Geological Survey of Canada.

Dr. David Eaton, professor of geophysics and head of the Department of Geoscience at the University of Calgary, echoes Young comments. “We need to think outside the box. Geology and geophysics students receive unique, hands-on exposure to important real-world problems, preparing them for many careers paths – from law to education – in addition to traditional professional employment in the oil industry.” The University of Calgary’s Geoscience Department has established four main areas of technical expertise: exploration geophysics, petroleum and energyrelated geoscience, environmental geoscience and solid Earth processes.

“The current generation of students across Canada is environmentally savvy. We need to demonstrate to them the fundamental role of environmental geoscience,” says Eaton, suggesting, at the same time, that oil and gas sector needs to dispel some public misperceptions about its environmental track record.

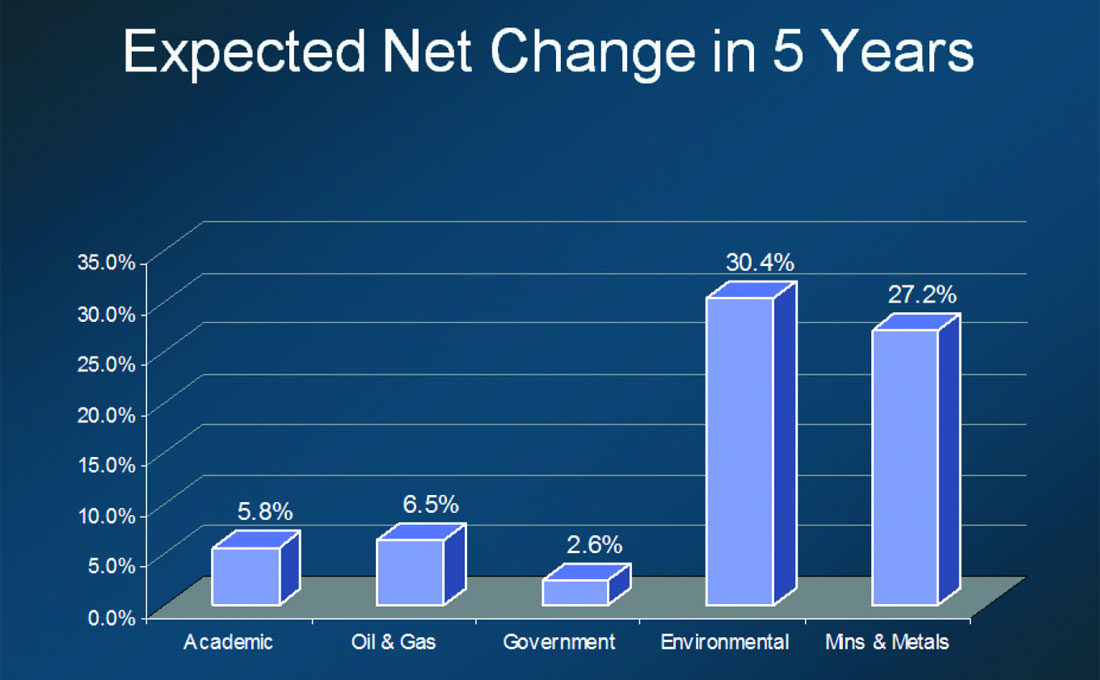

According to the CFES report, the environmental sector’s need for Earth scientists is expected to grow by more than 30% during the next five years alone – exhibiting a dynamic all of its own, this sector is attracting an ever-increasing percentage of Canada’s young geoscientists.

With a compliment of 480 undergraduate and 170 graduate students, the University of Calgary is, by far, Canada’s largest Earth science degree-granting institution – in fact, according to Eaton, his department represents approximately 15 percent of Canada’s entire undergraduate geoscience population. At a time when most other Canadian universities are experiencing falling Earth science enrolments, the University of Calgary – located at the epicenter of Canada’s oil patch – is recruiting new faculty members in response to increased student numbers and generous industry funding, including EnCana’s recent endowment of a Chair in Unconventional Gas Research.

Photo credit: Dr. Elisabeth Kosters, Executive Director, CFES.

“The Canadian oil patch is unusual, globally, in that it prefers Bachelor graduates for entry level hires, and molds them into the corporate culture,” explains Eaton. “It reflects a tradition here.” He suggests, however, that the current economic downturn may produce a greater demand for M.Sc. graduates who possess broader levels of expertise. “Exploration and production activities are getting more challenging,” explains Eaton, citing a growing focus on unconventional resources in Western Canada, a recently announced $100-million mapping program of the Canadian Arctic by the Geological Survey of Canada, and advancements in carbon capture and geological sequestration.

“As we move forward from conventional to unconventional resources, there are different skills required,” says Young about the changing face of oil and gas exploration in Canada. “We’re moving from ‘romantic’ pioneering exploration teams working in undeveloped basins, to a new reality where Earth scientists are part of multi-disciplinary teams trying to extract the most from the rocks.”

Photo credit: Dr. Elisabeth Kosters, Executive Director, CFES.

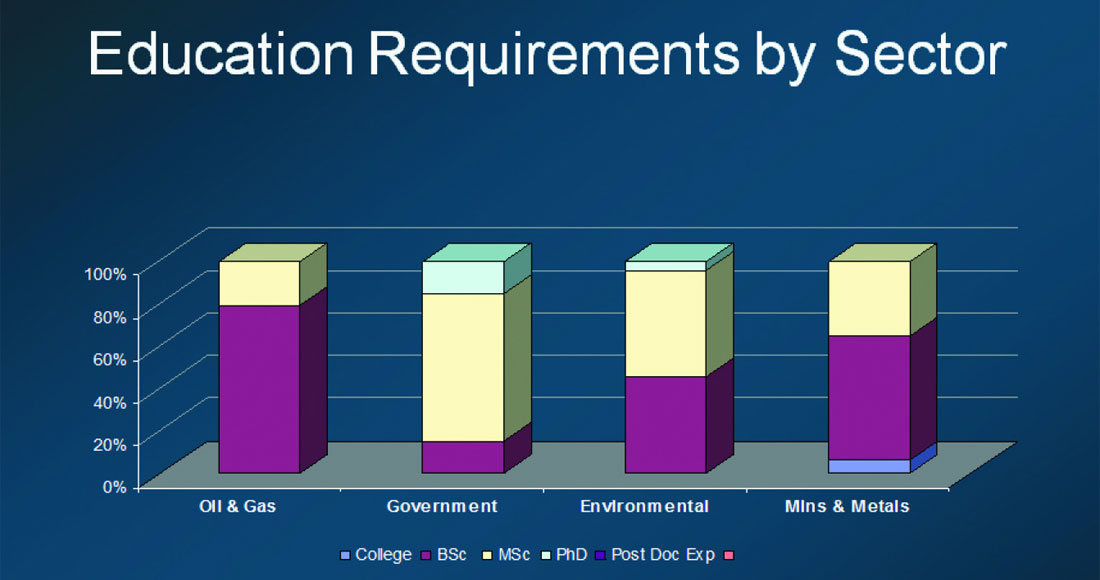

According to the CFES findings, education requirements vary by sector, with the environmental and mining sectors employing a far larger percentage of M.Sc. graduates than the oil and gas sector. Not surprisingly, government and research agencies hire Earth scientists with M.Sc. and Ph.D. degrees.

About the CFES

The CFES or FCST (the “Fédération canadienne des sciences de la Terre”) is an umbrella organization comprised of 12 technical and learned societies and interest groups, including the Canadian Society of Exploration Geophysicists (the “CSEG”). Striving to be the unified voice for Earth sciences in Canada, the CFES engages the general public, producing outreach, education and career materials on Earth sciences for K-12 school children and university students. Additionally, the organization advocates the use of sound scientific data to shape industry and government policies on resource extraction, the management of the natural environment and the mitigation of natural disasters.

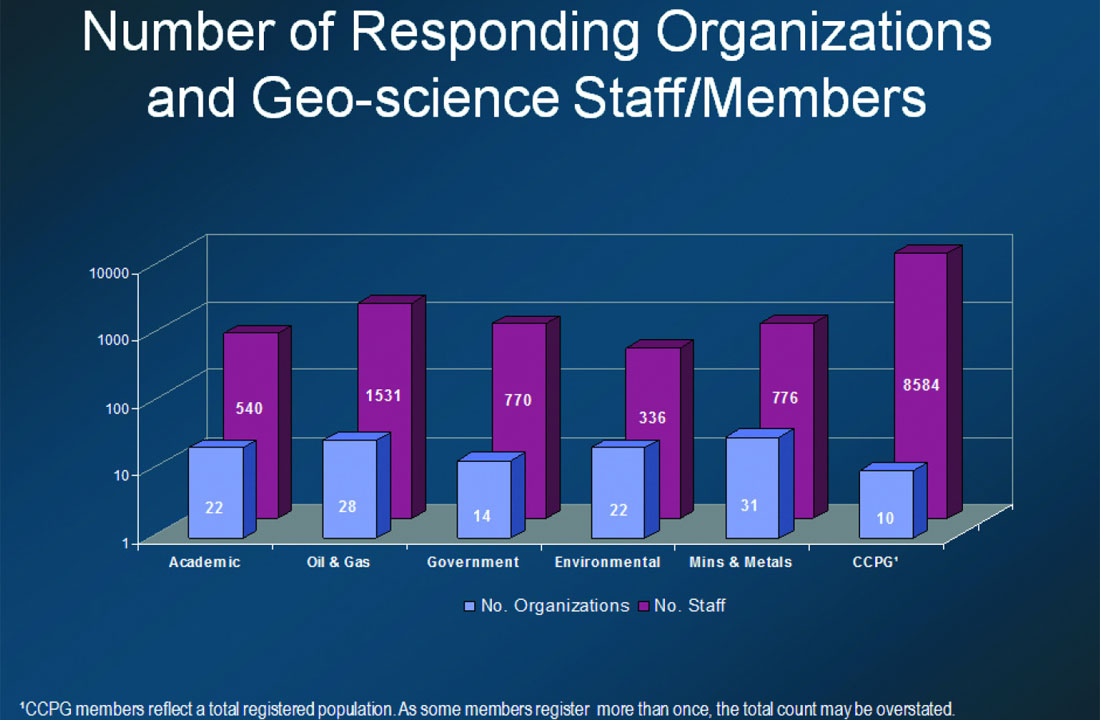

During its human resources study, the CFES polled 20 percent of Canada’s earth scientists, or roughly 4,000 individuals representing more than 117 organizations. Additionally, the CFES survey integrated data from 8,600 geoscientists represented by the Canadian Council of Professional Geologists (the “CCPG”). The CFES report can be viewed at: http://www.geoscience.ca/CFES_HR_requirements_Canadian_earth_sciences.pdf

“I like the CFES report,” says Dr. Dale Leckie, chief geologist at Nexen Inc. “It’s timely, appropriate and it agrees with the research I’ve been doing during the past couple of months.” Adds Leckie, “The data speak in the report.” As Nexen’s chief geologist, Leckie’s job includes the recruitment of new graduates, and the establishment of formalized, in-house mentoring and training programs for new hires or those individuals with zero to five years of industry experience.

Leckie, also president of the Society for Sedimentary Geology (the “SEPM”), an international technical organization, points to a shortage of young trained specialists in the oil and gas industry, a group that the CFES describes as the HQPs. “If we discourage the new graduates, we will be facing the same shortage when the industry picks up again. And, it’s not just layoffs – it’s also the lack of hiring.” At writing, Leckie indicated that Nexen was honouring job offers to this year’s crop of university graduates, while continuing to invest in the training of its new hires.

Demographic Crunch

François Aubin, president of the CSEG, was not surprised by the human resources trends charted in the multi-sector CFES report, especially those relevant to the oil and gas industry. “Our 2007 membership survey is even more lopsided, with respect to demographics,” says Aubin, the New Markets Business Manager for CGGVeritas. “As a Society, we really need to address this demographic crunch; our membership could drop by 50 percent during the next ten years, unless we’re able to attract new members.” Accordingly, the CSEG has ramped up its outreach and education programs – at junior and senior high schools and at universities – aimed at attracting students to careers in geophysics.

“The hiring of new graduates is going to be one of our greatest challenges,” adds Dr. Jon Downton, president-elect of the CSEG and CGGVeritas’ Research Manager for Canada. “We’re going to have to be very careful, going into this downturn, that we give new graduates meaningful work and opportunities.” CGGVeritas is a seismic processing company with different needs than oil companies, says Downton, and it routinely recruits from a diverse variety of backgrounds: geophysics, physics and mathematics.

In the face of dropping university enrolments and a growing capacity gap in human resources, Aubin asks: “Is there any way we can provide the same level of geophysical services (to the industry) with fewer people?”

“If we go back 20 years, we thought with the advent of computers, that we could have used a lot fewer people,” he answers. “But, we’re doing more work, today, with computers.”

“The industry keeps evolving and the type of work keeps changing,” says Downton, as the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin becomes more mature. Aubin points to the evolution of new seismic technologies like micro-seismic monitoring – applied to unconventional reservoirs and CO2 sequestration – as growth opportunities for young geophysicists. “It would be interesting to get some new minds looking at these new applications.”

Dr. Grant Wach is Professor of Petroleum Geoscience and Director of Energy at Dalhousie University, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Wach entered academia, after an oil and gas career which began in Alberta’s oil sands, and continued in the research and exploration groups of two major oil companies Houston. “My job is to begin to train the students, and to interest them in the opportunities in the petroleum industry. It’s the responsibility of the petroleum companies to promote careers in their companies, and, for the most part, they are failing to do so.”

“The petroleum industry needs to make work more exciting,” says Wach. “Right now, the jobs look like the civil service – here’s your workstation and in 25 years, you’re out.” Adds Wach, “Frankly, the Kingston Penitentiary looks more attractive.”

According to Wach, many young geoscience graduates are enthused about the outdoor field work component of their profession – accordingly, they’re choosing to enter the mining and environmental sectors, and are bypassing the oil and gas industry altogether.

Recent Earth science graduates are seeking companies who engage them by providing mentorship, training, career development, interesting and varied projects, competitive salaries and flexible employment options. Adding to this already expansive shopping list, some of these Generation “Y” candidates are choosing employers who mirror their personal values on issues ranging from the environment, sustainability, human rights, community giving and volunteer involvement.

Paul Bauman, manager of the geophysics division at WorleyParsons Komex, a Calgary-based environmental consulting firm which competes against oil companies to recruit geoscientists and engineers, believes that the youth of today are distinctly different. “Today’s graduates are leisure conscious – they want the best of both worlds. It’s a whole different work ethic.” Bauman suggests, as well, that young recruits also crave value-added mentorship in the workplace: “They want to flourish and they want to be nourished.”

Kelly Murphy is a human resources business partner, specializing in exploration teams at Devon Canada Corporation. “From a demographic perspective, the CFES report rings true, for us at Devon and globally,” says Murphy. “We see that hiring gap in the Generation “X” group, the 33- to 43-year-old geoscience professionals.” Adds Murphy, “The demographic challenges to Devon are not unique, but are common to the industry.” Devon describes the baby boomer generation as “the blue wedge,” a group who is slated to retire soon.

“Engagement is not a snapshot or an event – it’s not a one-time occurrence – and we need to recognize what makes employees stay or go,” explains Murphy, with respect to offering new hires training, mentoring, career rotations and succession planning.

Baby Boomers feeling impacts of financial downturn

The current economic downturn may provide a small silver lining for the oil and gas industry: experienced oil and gas geoscientists, the baby boomer generation, are re-evaluating the financial implications of retiring within the next five to ten years, and are delaying their inevitable mass exodus – the big “crew change” – from the sector.

“This downturn will keep people working longer, and it will alleviate the corporate drainage of technical knowledge,” says Leckie. “I think the pending grey bulge will be pushed out, and we’re seeing this in all technical disciplines.”

Murphy concurs: “We haven’t lost sight of the blue wedge – it was on our radar screen a year ago. The downturn gives us a bit of breathing room; it also gives us an opportunity to use the baby boomers as mentors to the Generation “Y” group, passing on their skills.”

“Recruiters know what’s coming,” said Catherine Brownlee, president of Prominent Personnel Ltd., a Calgary-based global oil and gas search firm. “The layoffs haven’t even started.” Co-author of the best-selling book, Want to work in oil and gas?, Brownlee has been flooded by résumés and has seen a significant number of retired geoscientists returning to the industry, casualties of the global economic downturn. “They’re willing to apply for positions advertising 10 years of experience, consult full-time or part-time, anything,” she added. “I’ve never seen anything like it: we have become a house of support for people who are desolate.”

In response to the changing economy, Brownlee’s firm has diversified its business model, gearing up for outplacement and career services. Recently, Prominent Personnel has also focused on creating training and mentoring programs for immigrant professionals, a group the CFES targeted to fill Canada’s growing capacity gap for Earth scientists. “I see this downturn as a perfect time for foreign professionals to prepare for the future,” said Brownlee. “They can sharpen their skills to get ready for the turnaround.” It’s also a great time,” she added, “for new geoscience graduates who are passionate about the oil and gas industry, to offer their skills (perhaps for a reduced fee) to the industry.”

CFES is the unified voice of more than 15 Canadian learned and professional earth science societies (which includes CSEG) and represents more than 15,000 practicing earth scientists in Canada. This open letter is viewable below for the information of all the CSEG members only, and CSEG does not necessarily endorse the contents of the letter.

View the The Canadian Federation of Earth Sciences / Fédération Canadienne des Sciences de la Terre open Letter to Prime Minister Stephen Harper here.

Join the Conversation

Interested in starting, or contributing to a conversation about an article or issue of the RECORDER? Join our CSEG LinkedIn Group.

Share This Article